The High Bretton Woods Era

The mass reindustrialization and suburbanisation of the United States in the post-war era, along with an American centred global economy, allowed Americans to live an affluent lifestyle far beyond anything that had come before it.

On the surface, the Bretton Woods system was generally working well as member states adhered to the arrangements and the economies of Europe and Japan steadily improved. Demand for American goods such as cars, steel, and machinery were high and a steady inflow of dollars across the globe was welcomed by everyone as world trade gradually increased and living conditions improved. However, even early on there were embedded structural problems with the system that could not be contained. How the U.S. would maintain a reasonable balance of payments, secure two reserve assets together (the dollar and gold), and provide liquidity to the system, all at the same time, was highly problematic. These were all problems that the international community would have to contend with, gradually leading to greater instability in the global economy as time went by.

This article explores how many of the Bretton Woods system’s built-in problems along with Washington’s own policies, domestic and foreign, helped accelerate an inflationary crisis, the Great Inflation, that would eventually lead to the system’s collapse and the global paradigm to shift once again.

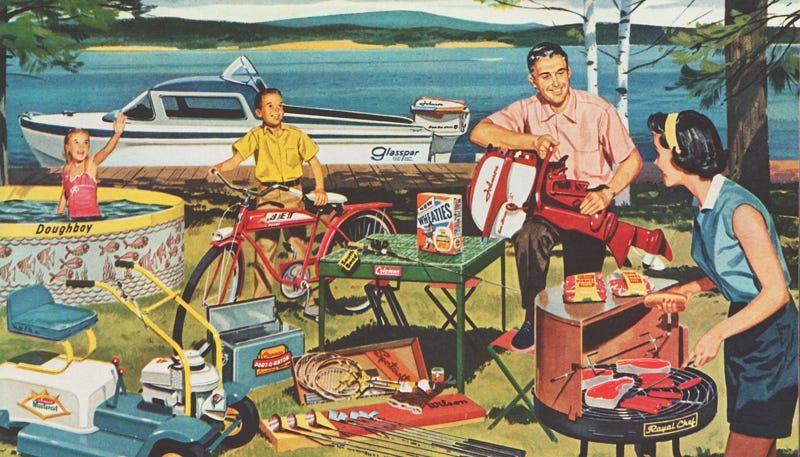

The 1950s is characterized as a period of sustained economic development and prosperity in the United States. This period is lionised in popular culture, by Hollywood especially, where picket fence Americana and the American dream were a lived reality, it is often called the golden age of economic growth symbolised by the iconic image of the Cadillac. War was over, employment was high, strikes were few and inflation low. Wages and benefits were improving all the time and job prospects were good nationwide. Consumer goods such as colour television sets and washing machines became accessible to many and shopping malls and fast-food restaurants sprang up everywhere. Huge infrastructure projects, such as the nationwide interstate highway, commenced. The U.S. economy grew by a staggering 37% during the 1950s, this level of economic prosperity America experienced had not been seen since the roaring 1920s as America achieved a standard of living that no other country could rival.

Meanwhile, over the Atlantic, Europe was also making great strides. Europe’s redevelopment was led by the Marshall Plan as America gave generous grants to European nations to help them rebuild their countries. Washington believed that economic growth in Europe and Japan would provide increased access for their goods and for capital investment, as well as providing a strategic advantage over the Soviet Union (the Cold War was just beginning) by allowing the U.S. to expand its sphere of influence there. From Europe’s point of view, rebuilding their severely damaged economies, industry and infrastructure was their foremost aim. Rebuilding their countries would increase prosperity and living conditions, in-turn improving morale and preventing the return of extremist politics and war. In western Europe especially, the era of war and conflict gave way to mutual trade and growing prosperity. The annual manufacturing and GDP growth in Europe was growing year on year and was as high as 8% annually for some countries.

In the aftermath of World War II, the world suffered from a shortage of available liquidity, thus the outflow of dollars was deliberately encouraged by everyone, but in order to provide the necessary liquidity the U.S. had to run a huge balance of payments current account deficit (meaning more money leaving the country than coming in) to assist in both the development of Europe and Japan and to rejuvenate the world economy, in addition to being able to provide conversion of gold into U.S. dollars. This deficit would obviously get larger as time went by. But given the condition that the world economy was in after the war, under a fixed exchange rates system where one nation is the sole creditor and is tasked with providing liquidity to the entire system and where no other alternative currency could provide supplemental leverage to prop up the dollar should the dollar encounter problems later down the line, maintaining a reasonable balance of payments that would protect both the U.S. economy and the dollar whilst providing the necessary liquidity to the global economy together was just not possible.

The danger was that, over time, the dollar would steadily lose value and this would erode the purchasing power of the dollar and with it confidence in the suitability of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency as well as the long-term viability of the Bretton Woods system as a whole. Countries holding dollars would see their holdings decline in value and its purchasing power reduced, in turn undermining the whole system. Potentially, this could lead to a run on the dollar further accelerating its decline. As I have stated already, it is important to understand that no other currency could provide additional liquidity to the system if the dollar ever faced a crisis. And face a crisis it would.

Washington was running balance of payments deficits from the 1950s onwards and had a current account deficit from 1959. Years of excessive borrowing and spending had caught up with the United States and as the 60s got underway America’s economic dominance had already begun to decline. Taking all of this into consideration, it didn’t take long for people to understand that, with more dollars in circulation than the U.S. could secure with gold, the U.S. dollar was overvalued, propped up by artificial demand and confidence that were both declining along with the dollar itself.

Another problem that was unavoidable is that large volumes of U.S. dollars were accumulating in central banks across the world. The looming threat was that if all of these surplus dollars came flooding back to the U.S. at once the inflationary crisis would be overwhelming and the U.S. economy could potentially collapse under the strain of all of this.

In 1960, a decade before the gold peg would eventually be removed, a Belgian-American economist called Robert Triffin identified this contradiction in what came to be known as “Triffin’s Dilemma’”. Triffin testified to Congress that if the U.S. failed to keep running deficits, then the global system would lose its liquidity and grind to a halt but, simultaneously, as the balance of payments deficit grew confidence in the dollar would erode as it became clear that the mass accumulation of dollars could not be secured by gold and that the dollar would depreciate in value as a result. At the heart of the Bretton Woods system there is a conflict of interests between what is best for the United States and what is best for the global economy. Failing to provide the necessary liquidity for international markets would mean that economic growth would slow down and the Bretton Woods system would no longer be viable. But, by the same token, a depreciating dollar would also spell the end of the system. The current arrangement could not support a strong dollar and provide the necessary liquidity to the global economy together.

As time went by the role of gold in the system was increasingly becoming a point of instability. At the time of the Bretton Woods agreement there was no alternative currency or asset that could provide additional liquidity to the system so it was decided that the dollar would be pegged to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This meant that the U.S. had to secure two reserve assets simultaneously; the dollar and gold but the problem with that is that one of these is highly elastic (the dollar) and the other (gold) is not, so an anomaly or disequilibrium was always a real possibility. At the close of World War II, the United States held $26 billion in gold reserves, approximately 65% of the estimated world total (the rest were in the possession of the Soviet Union). World trade was growing throughout the 1950s but supply of gold only increased slightly. This was because gold mining during the early Bretton Woods period was porous at best; the two countries that continued to source new gold were the Soviet Union and South Africa but these were not nations that the U.S. and its allies wanted to trade with (for different reasons). The problem was that gold reserves could not keep up with world trade and over time this would prove to be an increasing source of instability as the volume of world trade increased. Ultimately, Washington knew that every ounce of gold traded for U.S. dollars could never be recovered.

The only way the system could endure was if nations collectively promised not to convert dollars into gold but that became harder to do as time went on and as the dollar started losing value. This was problematic because an incentive would always remain to convert as the dollar slowly depreciated in value. This could lead to a domino effect and was, clearly, far from ideal. An obvious solution was to raise the price of gold but if that happened then countries, anticipating further increases in the future, may simply end up exchanging dollars for gold in the present leading to a run on the dollar. Also, raising the price of gold rewarded those that had done the most to undermine the system (countries that had sold off dollars in exchange for gold, namely France). Lastly, increasing the price of gold strengthened the hand of America’s foremost geopolitical rival, the Soviet Union.

Fundamentally, the U.S. was printing and circulating more money than it could secure with gold. Another problem that presented itself was that there remained an open market for gold, whilst central banks held gold reserves at a fixed price the price on the open market for gold was allowed to float, if the price on the open market for gold was more than the Bretton Woods fixed price of $35 an ounce countries would exchange their dollars for gold and sell on the open market for a profit. This could help solve internal economic issues and settle balance of payments deficits quicker. This also had the potential to cause a run on the dollar and destabilise the system.

By 1966, non-US central banks held $14 billion in U.S. dollars, while the United States had only $13.2 billion in gold reserves. Of those reserves, only $3.2 billion was able to cover foreign holdings as the rest was covering domestic holdings.

The Great Inflation

It is undeniable that many of the policies of the U.S. government accelerated the decline of the system. By the mid-1960s it was clear to everyone that the U.S. was printing more dollars than it could secure in gold and that the monetary policy of the United States was robbing the dollar of its value. Much of the inflation was caused by war, principally the Cold War and the Vietnam War whilst Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programme also contributed greatly, this came to be known as the “Guns and Butter” economy.

By the time it had concluded, the Vietnam War is estimated to have cost $168 billion (equivalent to $844 billion in 2019 dollars and $1.47 trillion in 2021 dollars), the war lasted almost 20 years and spanned the tenures of four American presidents. It is widely viewed as a catastrophe by many. The U.S. had to spend heavily to fight the war on its terms. In 1965 combat troops arrived and Operation Rolling Thunder, a campaign of sustained aerial bombing, commenced. The United States dropped 7,662,000 tons of ordnance along with over 20,000,000 gallons of herbicide and defoliant chemicals during the war. The Vietnam War required expansionary monetary policy that contributed greatly to the inflationary crisis; indeed, some have even called it the first American war waged solely on credit even going as far as to claim that Nixon closed the gold window and ended the Bretton Woods system in 1971 in order to pay for the war.

Lyndon Baines Johnson assumed the presidency in 1963. He wanted to eliminate poverty in the United States but knew that raising taxes to pay for social programmes would be unpopular to the American public (prior to him, Kennedy had cut taxes to historic lows). Between 1964 and 1967 spending on healthcare, education, housing, and other areas increased exponentially; education went from $4 billion to $12 billion and healthcare from $5 billion to $16 billion. Medicaid, the federal-state healthcare programme, was founded in 1965. All of this led to an unhealthy growth in the money supply to keep pace with all this Federal spending. Inflation was little over 1% in 1964, by the time Nixon ended the system 1971 it was over 6% but would continue to rise as the deficits compounded year-on-year. President Johnson refused to pay for these through increased taxation and the monetary inflation that ensued led to a deterioration of America’s trade position as surplus dollars flooded international markets. Johnson’s fatal error of judgement was his belief that he could run the Great Society programmes and fight the Vietnam War together without raising taxes.

As the 60s got underway the combined reserves of Europe and Japan gradually exceeded those of the U.S., and as their per capita income gradually caught up with America’s, the global paradigm once again started to shift and tilted away from Washington. Countries began trading among themselves more and more and the countries who had become the most successful economically saw their currencies strengthen against the dollar and this was a problem to which there was no easy solution. West Germany, who had revalued twice at Washington’s request before (in 1961 and 1969), had no intentions of revaluing a third time. Japan also did not want to revalue the yen. West Germany and Japan, who saw their export industries expand considerably, had no intention of assuming a weaker trade position and thereby making their exports more expensive (and thus less competitive) while the U.S. wanted to avoid devaluation in order to maintain the strength of the dollar and, as some (such as F. William Engdahl) have speculated, because Wall Street and the oil industry wanted to maintain a strong dollar. Devaluing means more dollars are required to purchase gold (and also, more dollars are required for America’s imports), this reflects badly on the currency and the nation who issues that currency. There was a clear conflict of interests between what was good for the U.S. and what was good for other countries. In the case of West Germany, Bonn had to revalue the mark in order to maintain greater parity with the dollar, this means the dollar buys fewer German marks, making West Germany’s exports less competitive in the process and thereby reducing their economic growth as a result. For West Germany, revaluing was akin to penalising an Olympic sprinter with a 10 second penalty because they were winning the race.

Numerous efforts were made to rescue the system including an expansion of the International Monetary Fund’s lending capacity in 1961, the formation of the Gold Pool and the advent of a supplementary currency called SDRs (special drawing rights) that were implemented late on but these could only be used to settle account balances between nations and were not accepted in global markets. Ultimately, the IMF did not have the available foreign currency reserves required to correct the enormous balance of payments deficit.

It was too late. A global crisis was now underway and both sides of the Atlantic had cause for concern. America’s capacity to secure overseas dollars with gold was called into question by Europe and Japan. Meanwhile Washington’s inflationary problems were growing and the long-term tenability of the Bretton Woods system was in serious doubt. West Germany, unwilling to revalue the Deutsche mark for a third time, formally left the Bretton Woods system, a move that would eventually strengthen their economy and led to a further decline in the value of the dollar. Switzerland would follow, redeeming $50m in gold along the way. Next was France, who exchanged $191 million in gold. With that U.S. gold reserves declined to their lowest level since 1938. The economic fortunes of the U.S. were spiralling out of control and on August 5, 1971 Congress, in an effort to protect the dollar, recommended a devaluation. In the first six months of 1971 alone, assets of $22 billion fled the U.S. This perilous situation was ultimately unavoidable, given the large volumes of dollars that had accumulated abroad and the declining value of the dollar.

Countries had lost faith in the Bretton Woods system, in the dollar and in the United States altogether and they wanted their gold back. In August 1971, President Nixon called an emergency cabinet meeting at Camp David attended by numerous cabinet members and high-ranking aides and it was decided that the gold peg would be removed, abolishing the direct convertibility of the dollar into gold. The broader international community were not consulted about this decision. With that the Bretton Woods system was no more, the fixed exchange system was discarded altogether and the U.S. was no longer responsible for having to secure overseas dollars with gold.

Even if the signatory nations to the Bretton Woods accords had honest and genuine intentions, the structural problems were just too much to contain and the U.S. had to shoulder too much of the responsibility and burden. Countries could not pursue free trade and maintain parity with other currencies at once and ultimately the discipline of a gold standard and fixed exchange rates proved to be too much for rapidly-growing economies at varying levels of competitiveness.