Whatever Happened To The Midlife Crisis?

Pondering over the cultural trope of the midlife crisis

It was my birthday this week and I quipped to my other half that I was at the prime age for a midlife crisis and she burst out laughing. I’m not actually having a midlife crisis but if I was and said so I know it’d be viewed as a big joke and something I was merely making up. Yet, during the 80s and the 90s the trope of the midlife crisis, especially in men, was ubiquitous. The midlife crisis was a Hollywood staple and viewed as an axiomatic truth and even a medical issue that could not be ignored.

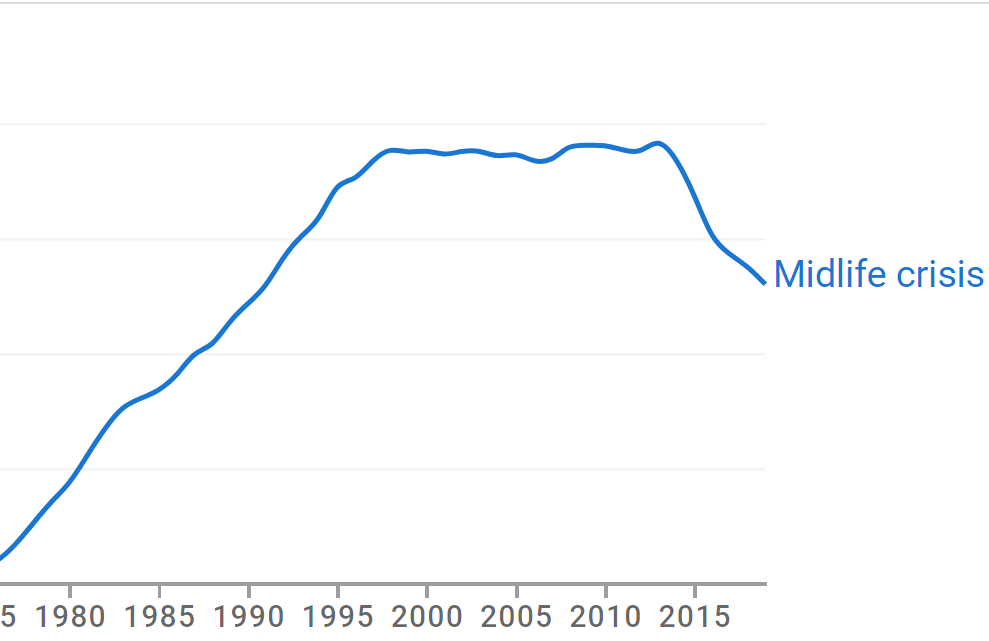

Since its heyday in the late 90s and early 2000s, the midlife crisis has faded into relative cultural obscurity. Google’s ever-helpful word usage counter is instructive here.

The midlife crisis has had its glory days as a meme, it’s past it and is now dwindling away in a rest home somewhere.

But what is it all about? What even was a midlife crisis?

The typical cliche of the midlife crisis is of a man entering his 40s or 50s and buying a Harley-Davidson motorbike or overly flamboyant power car. He would dress himself in the garb of his youth or try to present himself as a youth of the present. Often an affair with a younger woman would play a role in his crisis and all of it would be a mask concealing the sad truth that age was creeping up on him and there was no stopping it.

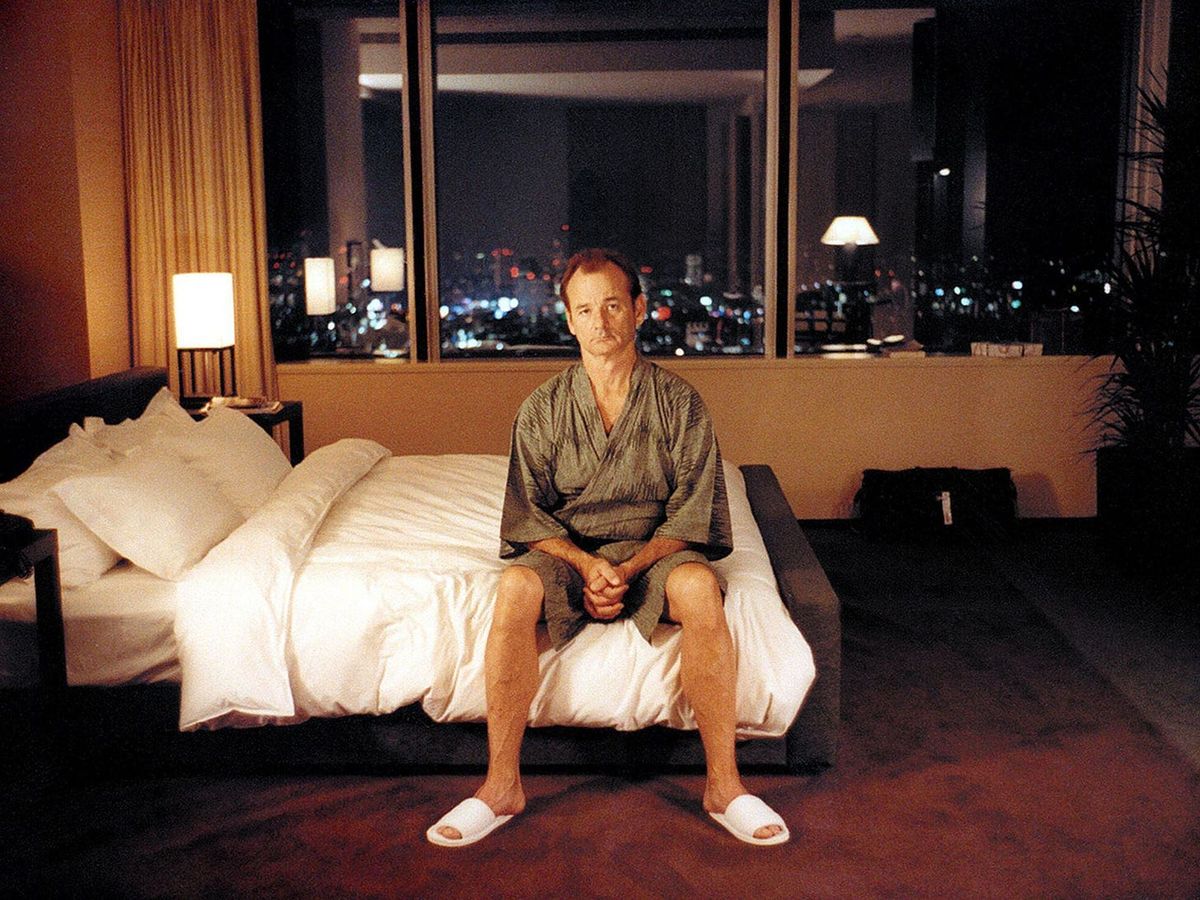

Hollywood adored the midlife crisis movie because myriad social and political themes could be woven into the narrative, as they did in American Beauty, Falling Down, Lost in Translation, City Slickers, The Incredibles, Wild Hogs, Thelma and Louise, Father of the Bride, Tin Cup and, indeed, most of Jack Nicholson’s career after 1980.

The massively popular and not overrated television show Breaking Bad is a later entry into the canon and probably responsible for the slight bump in the term’s usage after 2010. In the interestingly named Walter White we see once more the humdrum life of a middle-aged white man who has done everything society wanted of him but, in the end, feels profoundly unfulfilled until he is diagnosed with terminal cancer and begins life anew as a meth-cooking kingpin.

The midlife crisis man awakes one morning stares into the bathroom mirror, and wonders when the attractive young go-getter turned into the decaying husk he now sees looking back at him. He has a job he despises, kids who don’t appreciate him, and a materialistic wife who doesn’t understand him—long gone now, as Pink Floyd put it are ‘‘nights of wonder’’ when the taste was sweeter.

Fifty years before Walter White broke bad, American sociologist William Whyte wrote in The Organizational Man

“Man exists as a unit of society. Of himself, he is isolated, meaningless; only as he collaborates with others does he become worth while, for by sublimating himself in the group, he helps produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Like James Burnham, Whyte posits that the future belongs to managerial organizations regulating every facet of life. Man will become naught but a node in a network, he will sublimate his ego and individualism to it, or at least recast himself within its mold. It is a world of boxes and cubes. He leaves his box house in his suburban grid and travels in his box car to sit in his office block and stare at his box screen. His life will be reduced to a financial calculation and a series of payments predicated on him reliving the exact same set of routines over and over again until he reaches such an age that the system has finally squeezed every last drop of energy out of him and will allow him to retire on his already mapped out pension plan.

It is perhaps tragically ironic that in the 2020s the life of the Organizational Man is viewed with such awe and envy. Where Whyte saw the highly regulated worker ant filling his role in a super-organism, today’s online right sees a homogenous world of happy families and abundance in crime-free neighbourhoods. Something seemed to have gone terribly, horribly wrong.

The challenge of such a tightly regulated system is to account for individuality. Adam Curtis, in his documentary The Century of the Self, traces the interplay between the 60s Cultural Revolution and the wider organizational superstructure of America. The Organizational Man and the Marcusian Left were seemingly at odds with each other and a synthesis was needed to bring the tension to a conclusion. Here of course the Baby Boomers enter the story — which they must because it seems to me the concept of the midlife crisis is essentially a phenomenon specific to the Boomer generation.

The youthful Boomer’s rebellion against the ‘‘System’’ which in actuality means the conformist world of the Organizational Man, aimed to liberate the individual from the suffocating life on offer in the richest, most plentiful society in human history. If left unchecked such sentiment and ideology could begin to break the system and thus to avoid turning America into one giant hippy commune containment was needed to redirect the energy back into the superstructure. But how?

The answer to the riddle was to commodify individuality itself. Goods and products would transcend their utilitarian purpose and become conduits of self-affirmation and expression. Nike trainers were no longer for running in, they were symbols of freedom. We are all stardust, and we are golden, and now giant corporations and Wall Street are going to help you bask in your own specialness and uniqueness. Rebellion and revolution would become profitable subcultures and everyone would have a mass-produced Che Guevara t-shirt for $11.99. Anger, rage, and the yearning to ‘‘be different’’ would be provided by the managerial superstructure as consumption and product. The system would absorb all critiques and deconstruction of itself and sell them back to you, sometimes at half-price bargains too.

In this way, a young idealistic, anti-establishment Hillary Clinton can seamlessly transition into the epitome of the swamp creature.

As a cultural trend, the midlife crisis begins with the Boomers entering middle age and ends with them entering their dotage. All of the old critiques against the system, the yearning for individuality, and the rage against conformity were let loose one last time. It is the realization that all the ideals are fed back into the system and what is looking back at you from the mirror is the Organizational Man you once revolted against — except you have a collection of CDs that signal your non-compliance.

It is telling that the quintessential Generation X personality, Kurt Cobain, would go mad in his attempts to break through the containment trap. The more unhinged and vitriolic his music became, the more it sold. And it is here, perhaps, that we can understand why the midlife crisis seems to be ending with the Boomers; Generation X and Millennials never had the ideals of the Boomers, to begin with, and neither did the subsequent generations enjoy the heights of the post-war boom years. To look retrospectively back on the 90s is only to be reminded of an age of cynicism and postmodern snark. Indeed, it was in large part to live through the age of the Boomer midlife crisis.

A film such as City Slickers does not resonate with audiences today because its assumptive criticisms of the banality of Middle-Class suburbia seem redundant in an age where few people under 30 will ever own a home, let alone enjoy the 2.1 children and wife. The 1993 film Falling Down is also grounded in the Organizational Man’s rebellion but it, unlike City Slickers, absolutely does resonate today. In Falling Down the dream of suburbia has become just a distant ideal and memory in a world of inter-ethnic crime, squalor, and civilizational decay.

To answer the question of why the midlife crisis is a fading cultural trend we must understand that it isn’t actually a universal or permanent feature of life but rooted squarely in the life cycle of the Baby Boomers, their ideals, and frustrations. However, it is also to recognize that the time for such indulgence is over and real life and struggle are finally re-entering the story of modernity. The tightly ordered world of the Organizational Man is viewed with envy by today’s online right because its rejection is all that anyone has ever known — the lament is a permanent state of Being. Very few people under fifty have the luxury of lamenting how boring their life is in a three-bedroom semi-detached house with two kids and a garage. Neither did they have the prerequisite ideals that would view such a life with contempt.

This is not, however, just another bash-the-boomers exercise routine. The midlife crisis trope featured valid questions about finding meaning within modernity, and that is a question that remains unanswered, even as the superstructure begins to fall apart around us.