Transcendences

Between limits and possibilities

One of the most natural of human desires, a desire that is arguably at the very centre of everything we are and do, is the desire for transcendence. But as with all natural things, all apparent givens, this desire is part of the background of life. It is therefore easily forgotten and easily misunderstood. Against the grain of this forgetting and misunderstanding, though, I want to briefly interpret this desire by suggesting that transcendence is not a simple, singular thing. There is no mere desire for transcendence since it always involves a gathering of various desires for various transcendences. The desire for transcendence exists as a kind of polyphonic harmony within and beyond the human soul that forms according to three different modes. There may be, and likely are, many specific desires that can be accounted for within these modes, but these modes remain consistent and universal.

To explain what I want to explain, I draw here on the thinking of William Desmond who, in his masterful work God and the Between, articulates three kinds of transcendence—what I have suggested as three modes of transcendence. To understand these better is, I believe, to have a way to understand how our particular desire for transcendence might be taking shape. This can also help us to notice in what ways our desire for transcendence may be distorted and corrupted. It may also help us perceive, if only in a very provisional manner, how to set our natural inclination for transcendence on a better course.

To reflect on this, I want to look at a tragi-comical example in the form of the scene between Mowgli and King Louie in Disney’s The Jungle Book (1967), where King Louie the Orangutan breaks into song and admits something of how he perceives transcendence.1 The comical ape, perhaps a symbol of man’s primate past, sings about the fact that, even though he is a king, that is not enough for him anymore. He’s “the jungle VIP” but he’s got a problem. He’s “reached the top and had to stop”—and that’s really started to get his goat. The poor king is at the very pinnacle of the evolutionary order of things but he wants more. In fact, he wants to be “a mancub.” He wants to “be just like the other men.” The joke is on him, of course. He can’t not monkey around, but he doesn’t know this—yet.

We are all likely to feel something of what Louie expresses in the scene, though. If we were to arrive at a specific state of being at the top of a hierarchy only to be told that we’ve reached the end of the line, we’d be just as bothered as he is. It may turn out that Louie is mistaken, though, as I get to in a moment; in that case, his perspective on transcendence may be at fault. But how can we tell? I’ll get to that too.

Transcendence exists, in the first place, as a simple sense of otherness. Call this first transcendence. Things transcend each other, just as they transcend us, by simply being different from each other and different from us. A cat transcends a dog by not being a dog. A rat transcends a blob of ice cream by not being a blob of ice cream. I transcend you by not being you, just as you transcend me by not being me. This first transcendence functions horizontally. It functions non-hierarchically. The chief mode of its operating is along the lines of hierarchy-free difference, as well as our ability to recognise the limits of any given thing. There is no better or worse here, just different. This is the sort of transcendence that postmodernity is endlessly fond of. The Other always speaks—and we should listen to him or her or it, apparently, simply because it is the Other. This may be part of the truth but to take this as the only kind of transcendence is worrisome. It places a false limit on the meaning of transcendence. There is an Other, of course, but there is also a Self, and there are networks of relationships not reducible to simple binaries. To know this, however, is already to be stumbling into second transcendence—we’ll get there shortly.

Since our consciousness is structured along the lines of metaphor and analogy, we cannot help but think of everything in terms of other things. Still, first transcendence involves the recognition that there is no way to simply reduce things to each other. Things stand in (at the very least) a horizontal relationship with each other and, in this, they raise several questions: Why does this other thing exist? What makes this specific existence possible? Why is this thing like this and not like something else? Why are there beings and not nothing? Embedded in such questions is the mystery of existence itself. Everything feels terribly contingent and yet there it is, manifesting itself as itself and not as something else. As this would suggest, the very possibility of further transcendence is opened by this basic first transcendence, which Desmond nicknames T¹.

Before we get to a further mode of transcendence, though, it’s helpful to see T¹ at play in our example of King Louie. He sees Mowgli as a model for transcendence simply in his otherness. He transcends Louie in his sheer exteriority. He is not Louie and this is what Louie likes about him. On the one hand, this sense of transcendence may be a helpful guide to our transcending, as would be the case when a disciple wants to emulate his master in order to be better than he (the disciple) currently is. On the other hand, though, this first transcendence can be misleading. We may attach a false hierarchy to the brute fact of difference, as Derrida does in order to force the world through the meatgrinder of deconstruction. As a result, a certain uniqueness in the otherness of the other can be mistaken as a directive. Instead of seeing the other as the other, a secret command seeps in. You should be the other. René Girard calls this metaphysical desire. It is the desire to possess the very being of the other. King Louie sings about it: “Shoobedoo, I wanna be like you, oo, oo. I want walk like you, talk like you,” etc, etc. It sounds so cheerful. What’s so bad about that?

It seems obvious to me that this sort of thing is dominant in influencer culture and consumerism in general. The influencer adopts signs—the appearance—of a certain lifestyle and then, by appealing to our natural mimetic desire, encourages his or her audience to embody those same signs. But signs of this sort of transcendence are everywhere. People might change their worldview or adopt a different ideology or may even alter their appearance in significant ways, not because it offers real transcendence but because it offers a false transcendence. They feel so similar, after all, that the difference may seem negligible—although it is not. Someone might convert from Calvinism to Catholicism, for example, or from Christianity to atheism, less because of their attunement to an authentic drive to attain a higher awareness of the truth than because the new worldview provides tools for reflecting on and often negating their previous worldview.

This is often the logic behind being “whatever-pilled”—red-pilled, blue-pilled, black-pilled, light-pilled, woke-pilled, and so on. The metaphor of waking up from the Matrix is the primary cultural reference here but this sets up the erroneous assumption that waking up necessarily means waking up to reality. But that we wake up to reality is not a given at all. This much should be obvious by the fact that, in the end, the fourth (and rather atrocious) Matrix movie essentially endorses a view that there is no escaping the Matrix. There can be no true freedom of the mind either: what matters, for the Wachowski who ended up making that movie, is not transcending the Matrix but ensuring that you get to be the one in charge of the system of control. The Gnostic tale many supposed was embedded in the first film gets retconned into a trans allegory: immanence was always the point, not transcendence, apparently. But what a sad and cynical story. Power, not truth, is ultimately what matters in this view and power, as we all know, is a terrible measure of what is true. As this suggests, we may very well ‘wake up’ to a new illusion: the experience can be so dramatic that it may feel like a real awakening. Or awokening. It may really be the case that we have fallen into a deeper state of dreaming.

That which transcends us in its sheer exteriority is experienced as both a limit and a possibility, and relating rightly to these two dimensions of the experience is essential to relating rightly to the world. In fact, limits and possibilities accompany all aspects of transcending. The otherness of a guitar, for example, the very limit imposed on me by its guitarist otherness, invokes in me a desire to play, a desire for a specific, bounded arrangement of possibilities. But I can only play the guitar as I am, in keeping with certain limits within my being—the limit of having learned to play left-handed, for instance, and especially the awful limit of my not being a very good guitarist. I will never play the guitar like Leo Kotke but this will not destroy the fact that I rather enjoy the combination of limits and possibilities that the instrument presents to me and within me.

I think this is what St. Paul means in his first letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor 7:20): “Each person is to remain in that state in which he was called.” I don’t think he means that we should insist unquestioningly on stasis over change but that we should confront the fact that any changes we undergo will largely be incremental and in accordance with where we find ourselves. A caterpillar may turn into a butterfly but it cannot turn into a mongoose. That said, authentic conversion is possible—I have seen it in others and experienced it in myself. However, many of the changes and micro-conversions we go through in our lives have little to do with real transcendence and everything to do with the restlessness we all carry with us that refuses to let us stand completely still. Without a higher sense of transcendence, third transcendence discussed below, there is no way to tell the difference between a difference and genuine transcendence.

But we should first look at second transcendence before getting to third. Desmond nicknames this T². This refers to self-transcendence. Where T¹ focuses on transcendence as determined externally, T² focuses on the interior dimension of transcendence, the natural inward desire to transcend. Hegelian self-mediation has the stench of just a little too much T², although the great man at least tries to make room for T¹. While T¹ seems to confirm the Girardian thesis that all desire is mimetic—desire is emulated, borrowed and/or copied—T² suggests that perhaps not all desire is mimetic after all. We do, after all, possess a natural will to become; that is, an innate desire to determine the nature of our own self-transcending. There is, in this second transcendence, a sense of real freedom. We can reach beyond ourselves. We can will-to-power our way into some equivocal or determinate beyond. How lovely.

Clearly, there’s something of both T¹ and T² in being “whatever-pilled.” There is also something of an evaluative hierarchy here in the combination of the two transcendences. The former worldview is deconstructed to give way to a worldview that has its own advantages. But there’s a danger in this. The danger is that the limits of the new ideological “pill” aren’t recognised. “What radicalised you?” is a question that is often thrown around today in reference to the fact that, all too often, the pull into new ideological terrain is merely a reaction against the bothersome aspects of the old ideological terrain. The new “pill” is often only a way to perceive the failures of the previous worldview but it is not necessarily the way. The experience can be so liberating, though, that it can feel more transcendent than it is.

The #walkway movement I saw trending a while back is one potential example of this. So many people ended up on the political right mainly because the new left is filled with loonies and lunacy. No doubt, such a movement could mean the recovery of genuine principles. In such a case, perhaps it is redeemable. But mere reactivity is a sign that further reactivity is likely, especially where negative freedom is the only kind available to the liberal psyche. Who is then to stop another totally different kind of #walkingaway from happening at a later date? Essentially, a certain T¹ and T² combination can land a person in a new Matrix. One illusion may be substituted with another. Without teleology, we become victims of a mere process.

Still, second transcendence is a natural component of our lives. We all have the desire to not only persist in our being, which Spinoza named the conatus essendi, but also the desire to grow. This is biological but not just biological. Just as children naturally want to get bigger and stronger, they naturally look at their parents and elders as potential prophecies about themselves. They naturally find not only an exterior sign of transcendence (T¹) but also find within themselves the capacity to become more (T²). Certainly, this is something of what Nietzsche was indicating by his famous paradox: become what you are. Our becoming goes ahead of us and calls out to us to reach beyond ourselves, to grab hold of what we are yet to be. We feel that we have a destiny, even if we do not always know what to make of it.

Second transcendence points to what is true, although it cannot ultimately stand alone. It is possible to pick up healthy habits, to train our bodies and minds and spirits. We can become physically fitter and we can become more virtuous: more patient, more honourable, more courageous. But we can be misled by second transcendence, too, as we can be misled by that equally natural first transcendence. Louie is, once again, a decent example of this. He wants to be a mancub. But the joke is on him. He cannot be a mancub, no matter how hard he tries. Acquiring “man’s red fire” won’t do what he thinks it will. His destiny is not the same as Mowgli’s. He has confused T¹ and T². He thinks that his own natural desire for self-transcendence will be best accomplished by being what he is not. Again, St. Paul: “Each person is to remain in that state in which he was called.” To deny this is ultimately to fail to seek self-transcendence; it is to seek self-negation instead. Far from confirming the value of the seed that gives rise to the oak tree, it is to betray it. False transcendences always betray being.

There is another way that this second transcendence may be misleading that I should point out, especially since it is so prevalent in Western culture. I’m thinking of the case of self-help literature, which seems to be the literature of neoliberal consumerism. The literature is part of an entire industry. I know there are genuine merits to attempting self-improvement, and this is not what I am taking aim at. I applaud any real attempt at growing as a person. But, as the always-perceptive writer Caleb Caudell has noted, one of the reasons that the self-help and advice industry “are so compelling to so many” is “not because people want to change, but because they enjoy the feeling that they could.” The authentic effort to improve is soon corrupted by the culture of expressive individualism.

Caleb Caudell @LitMiddleSelf help and the advice industry are so compelling to so many not because people want to change, but because they enjoy the feeling that they could11:03 PM ∙ Nov 5, 2022

This is to say, our feelings towards any kind of transcendence can be fantastically misleading. Every authentic expression of transcendence has its counterfeit double. We may rely too much, as Desmond notes, on our conatus essendi—the grasping desire for existing—and not enough on the passio essendi—the letting-be and suffering of existence, which has its own rhythms and gravitational graces. Some growth is natural but the temptations of false transcendence need to be resisted.

Equally important to notice is the perfect storm of T¹ and T² that arises in belonging to a group. Of course, a group of people can be a powerful support for real transcendence. But in an age in which real transcendence is so readily denied, the crowd, even the virtual crowd, becomes a terrible temptation to us to get stuck in our illusions. Moreover, in an age of alienation, the need to belong gains an urgency that is often impossible to resist. Why resist what will take the loneliness away? All I will say to this, for now, is this: truth is seldom urgent. Like love, it is patient and kind and not envious in the least. It does not boast and is not proud. Yes, I’m quoting St. Paul again. He knew a thing or two.

In all of the above, what should be clear is that transcendence is not a simple given to be reduced to our most immediate intuitions. We cannot merely assume that our current understanding of transcendence is right. The adolescent who assumes that she will transcend herself by self-identifying as non-binary or even as a boy, for example, is nothing but deeply and tragically deluded. Perhaps she recognises something true in some otherness that she cannot experience for herself and yet she sees this truth only through the lens of self-annihilation. She may want to be born again, so to speak, but her mistake is the same as Louie’s. She takes the wearing of particular signs, the adoption of a passable surface, as sufficient for covering over or perhaps healing deep wounds. She mistakes a deep self-othering, a self-loathing, a denial of her being (the denial of T²), as correct.

But genuine second transcendence, which is discernable only when we get past our pain, makes accessible a profound possibility: the acceptance of who and where and how we currently are. Genuine T² includes the recognition of a certain limit to certain aspects of transcendence and a realistic sense of possibilities. We might recognise, for example, that there is something remarkable in certain dimensions of T¹ without assuming that we ought to relinquish ourselves for its sake. It is possible to admire the qualities of someone else without assuming that we should become them. I admire Leo Kotke’s guitar playing, as I’ve suggested, but I will never be Leo Kotke.

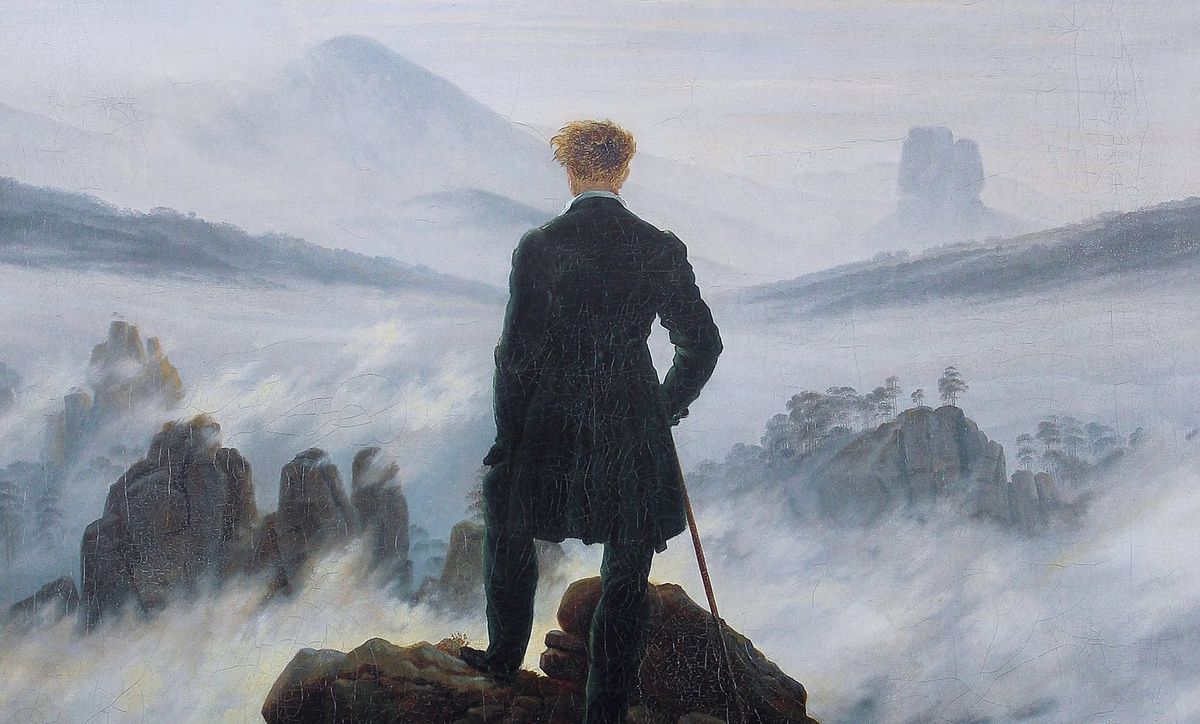

However, to see the truth in our transcending, we need to note a higher level of transcending. This would be—at last we get to the crux—third transcendence, which Desmond nicknames T³. This is “original transcendence as still other—transcendence itself, not as the exterior, nor as the interior, but as the superior. This would be a hyperbolic sense of transcendence, bringing to mind the question of God beyond the immanence of transcendences in nature and human being.”

First and second transcendences both beg the question of why there is transcendence, not mere brute thereness. Why must the tadpole become a frog? Why must a frog (symbolically, not literally) become a prince? Why must self-help literature exist at all? The answer: because there is within the deep structure of reality a call for transcendence that exists beyond first and second transcendences. Even Darwin saw this, even if he did so through a reductionist and ultimately immanentising lens.

What perennial tradition says of this is simple: we exist for God. We are called by God towards our highest good. And our highest good is not in competition with God, either, in the end, since the gap between his Being and ours is infinite and insurmountable. For us to achieve the highest ends for which we were made is therefore to achieve union with the divine. This is not to somehow transcend the limits of the human but to finally appreciate and conform to those limits. The human is a limit and a possibility, after all. This is partly why Christianity insists on Christ as true man and true God: perfect union means perfect transcendence, and this means becoming what we were always made to be. Nietzsche saw becoming what we are as inherent in T¹ and T², but the truth is that these need a third transcendence to be what they are.

We feel this natural desire for third transcendence even in its demonic form in King Louie’s song. His desire to take hold of “man’s red fire,” such a Promethean urge, is mistaken in some ways. And yet it still recognises the truth of third transcendence. It is only by a third transcendence that we can measure the truth of the first and second transcendences. This is a transcending power that cannot be subjectified or objectified but which, as Desmond writes, “stands guard over all our thinking, and the thinking of what is other to our self-determination.” Still, it is telling that the Promethean urge is essentially destructive. What Louie admires is not man as he truly is—indeed, he does not even admire monkeys for what they truly are. Rather, he admires a degraded version of a man: the man who will set fire to the world. Louie reflects into Mowgli a false sense of himself, too. Mowgli therefore also needs to have his sense of transcendence placed in check. And we do too. Constantly.

Modernity and its aftermath have tended to more than imply that T³ is not possible, though. As a result, T¹ and T² are more easily mistaken for T³—and endless permutations of false transcendence have been the result. Most forms of being “whatever-pilled,” for instance, play out the dominant culture’s resistance to T³ and so end up being refusals to travel past the limits of their own perspectives. Everyone ends up waking up to another Matrix. This is partly why tribal affiliations have such a tight grip these days. They are the best substitute we have for something that holds us together (T²) while pulling us beyond our limits (T¹). But any substitute for genuine transcendence is ultimately no good. After all, to rely on substitutes is ultimately to forsake all transcendences—T¹ and T² included. This is one reason why those who have only T¹ and T² at their disposal tend to adopt a degraded vision of life. To attempt to rise without receptivity to the grace of a Genuine Otherness, which draws us beyond ourselves, is like attempting to yank ourselves out of a bog by our own hair, as Baron Munchausen does.1

It is a strange and sad sign of our times that I need to point this out but point it out I must. I am, for the record, refusing the racial reading that has haunted this scene since its early days. This is not how I first encountered the scene as a child. In fact, I think that anyone who wishes to read the scene along racial lines is depraved. The producers famously elected not to cast the great Louis Armstrong in the scene, despite being fans of the man’s music, because they didn’t want the scene to contain any potentially harmful messaging. I am glad they made that call. I take this alone as a sign that we do not have to degrade what was never intended to cause hurt and division by looking at it askew.