Through The Upper Country

Pierre d’Iberville And The Hudson Bay Expedition

Editors Note:

Canada, it’s early history and it’s people, was shaped by the twofold struggles between it’s people and the hostile environment, and between it’s peoples for dominance. The story of Pierre d’Iberville is a great window through which to observe both these struggles at their most primal. The Red Ensign asks the reader to take the opportunity to reflect on who we are, and all that we could be again.

West of Montreal the Ottawa River winds slowly northward through the Laurentian Highlands. It passes by the limestone cliffs of Parliament Hill and continues for a while through a broad, fertile valley before narrowing suddenly just north of its confluence with the Petawawa River. From there it goes north through a thick, dark forest of pine, spruce and fir, with little hamlets and cottages clinging to its waters, before broadening into Lake Temiskaming and curving west into the frozen vastness of northern Quebec. Here the soil all but disappears, and the muskeg-choked waste of the Canadian Shield begins to dominate. From there to James Bay lie three hundred miles of rock, swamp and woodland, dotted with thousands of lakes and cut with as many rivers and streams. This is the Pays d’en Haut, the Upper Country, the cold, silent land that stretches on and on west of the St. Lawrence. Even today it is rough, inhospitable country, sparsely populated and difficult to traverse.

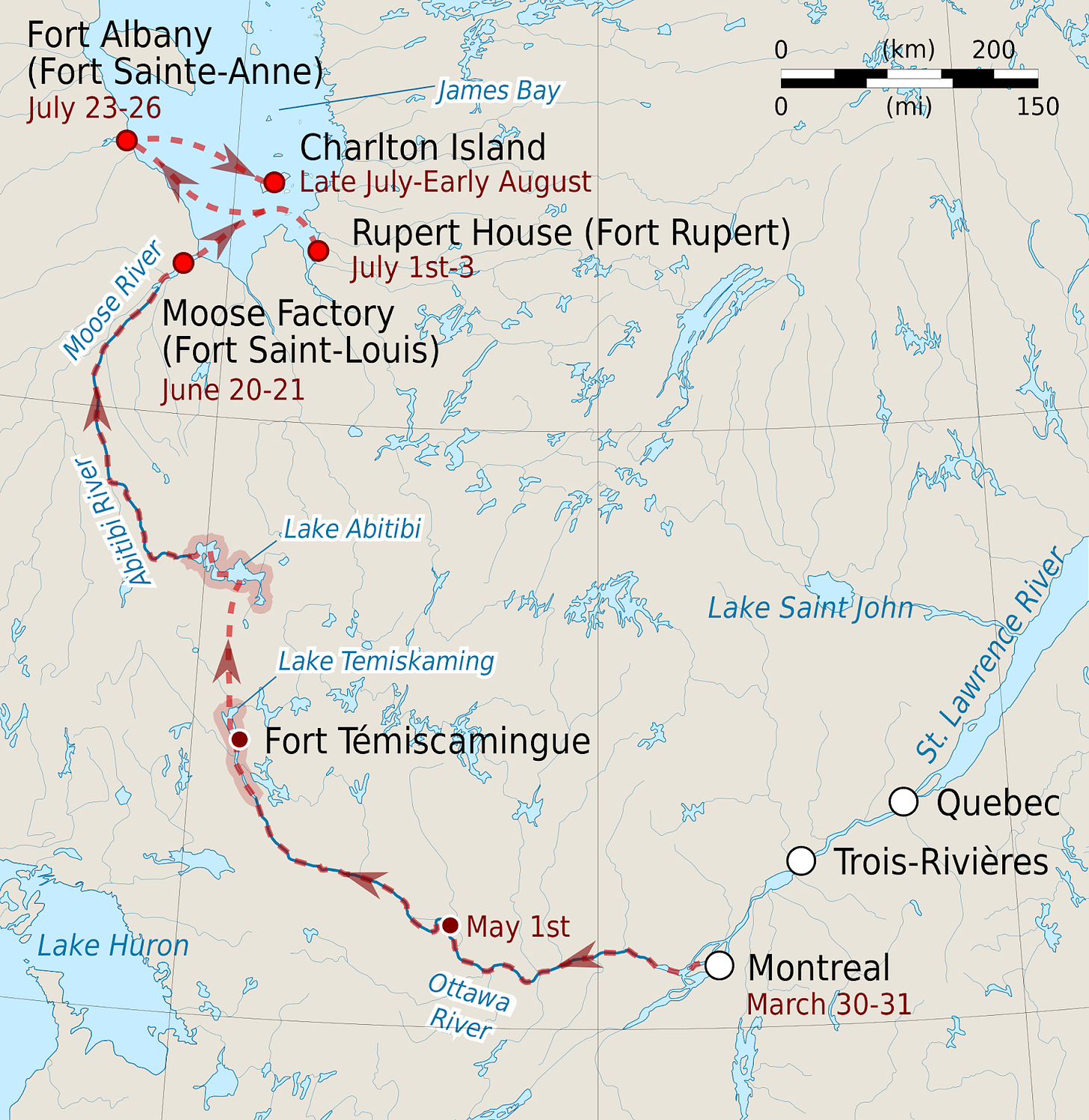

Three-hundred-and-thirty-seven years ago at the end of March, just over a hundred men left Montreal and began a gruelling eight-hundred-mile trek through this harsh uncharted wilderness. In the empty vastness of the Pays d’en Haut they would encounter impassible bogs, deadly rapids, sheer cliffs and unpredictable weather. This intrepid company had as their sole objective the capture of the three English forts in James Bay, built and manned by employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The English presence on the Bay had begun over fifteen years before the expedition was launched. Under a royal charter from Charles II the Hudson Bay Company established several forts on James Bay at the mouths of the Albany, Moose and Rupert rivers in the early 1670s. The natives of the Canadian Shield were thus incentivized to follow these rivers north to trade their downy subarctic furs instead of making the treacherous southern journey to Montreal. Over the next decade and a half the French lost almost all access they’d once had to the northern tribes, and were further troubled by the presence of an English outpost on their northern border in addition to populous New England to the south.

Something had to be done, and in the winter of 1686, a plan was finally hatched. The Marquis de Denonville, then governor of New France, charged the Chevalier de Troyes, a French army captain who had arrived in the colony the previous summer, with leading a party north through the empty reaches of the Pays d’en Haut to capture the English forts on James Bay. They were to travel by snowshoe and canoe, trudging across the Laurentian ice as long as they were able before riding the snow-swelled Abitibi down to James Bay.

De Troyes contributed thirty French regulars to the company, and raised the remaining seventy men from among the Canadians. Among them was a young man of seigneurial birth, Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, and his brothers, Jacques de Ste.-Hélène and Paul de Maricourt. Pierre d’Iberville was only twenty-five years old at the time but was selected as the second lieutenant of the group, and as a result was responsible for the lives of a large number of men. It was a role he accepted with honour and, as it turned out, was more than capable of playing.

Already at his young age d’Iberville was an accomplished seaman, having trained with the French navy from the time he was fourteen and captained several transatlantic voyages by the time he was twenty-two. He was a tall, broad man, fair of hair and face, universally described by his contemporaries as handsome, athletic and cool-headed. Few in New France had cut a more dashing figure than d’Iberville since Champlain first made his way up the St. Lawrence eighty years before. He was strong, capable, and well-liked by all he knew, and was thus the perfect choice as a lieutenant in de Troyes’ company.

The party set off from Montreal on the thirty-first of March, travelling by snowshoe over the frozen Ottawa river. Their trip up the Ottawa was fraught with a number of difficulties. In the first two days several men fell through the ice and had to be rescued. Rain and wind lashed them, forcing them to stay put for days at a time. A man cut his finger off, another burned his hand, and several fell ill with diarrhœa. At the infamous Long-Sault rapids near Carillon, Quebec, less than a week into their trek, two men got drunk, lost their canoes in the rough water and began arguing to the point where they threatened to kill one another. After de Troyes had arrested the two men and taken their brandy ration away, d’Iberville, in a show of his physical capabilities, went out into the rapids to retrieve the canoes. His skill as a canoeist was unmatched among those in the company, so he was able to collect both vessels, “which he restored for service as best as he could.”

For weeks they journeyed on “through woods dreadful in their loneliness,” taking in the solemn grandeur of the pristine Canadian wilderness. They met several Indians, whom they befriended and took along as guides. On the nineteenth of May they arrived at Fort Temiskaming, an outpost of the fur-trading Compagnie du Nord, for whose benefit the entire expedition had been organised. There they spent some time recovering before setting off once again on the twenty-fifth. The company had hardly departed the fort when they were caught in a forest fire; remarkably, they emerged more or less unscathed, losing only one canoe and no lives. On the second of June they had arrived at Lake Abitibi, deep in the largely uncharted reaches of the Pays d’en Haut. They were, as far as anyone knows, the first white men to dip their oars in the lake’s waters, so they constructed a small fort on its shore and left four men to guard it while they carried on into the wild.

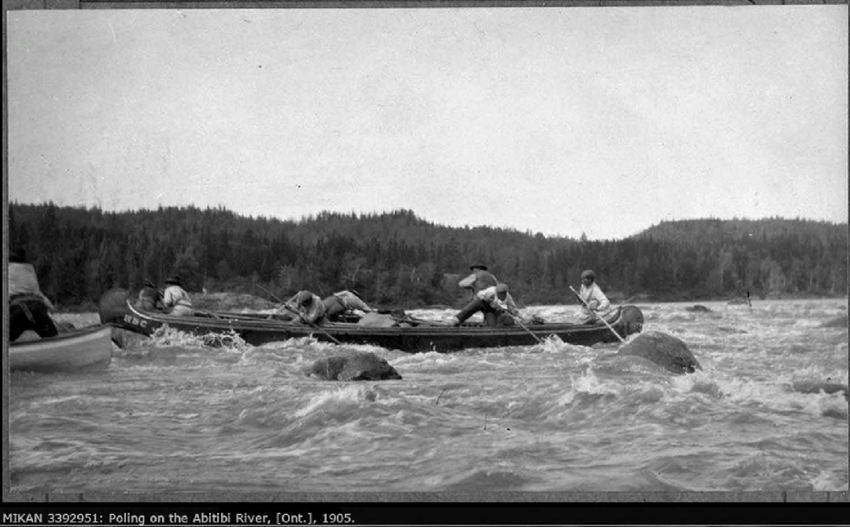

By now they had entered into “a country of rocks, full of lakes”, through which the Abitibi River winds its frigid course to Hudson Bay. This leg of the journey would prove deadlier than any other; the Abitibi roars through deep canyons and flows swift and white over sharp rocks. Runoff from melting snow in the north woods ensured that the water would be higher and faster than normal, making the many rapids along the river all the more frightening for the company.

It was under these conditions that disaster struck for d’Iberville and “one of [his] best men,” a young Canadien named Noël Leblanc. On the tenth of June, as they attempted to run a rapid, their canoe capsized, throwing both men from their seats and dragging them underwater. D’Iberville was able to escape death only through sheer force of will and physical strength by swimming through the rapids to de Troyes’ canoes, but his companion, unable to swim, never resurfaced. The young seigneur lost all of his supplies in the accident, and was no doubt shaken by the loss of his companion Leblanc, but he pressed on, determined to capture the English forts and reassert French control over the North.

On the 19th of June d’Iberville and the company of de Troyes finally arrived at the mouth of the Moose River, where the fort of Moose Factory stood between James Bay and the boggy black-spruce wastes from which he and his companions had emerged. De Troyes ordered them to halt some distance from the fort, while a small party was to reconnoitre and report back with what intelligence they could gather. D’Iberville and the Sieur de St.-Germain, captain of the guides of the expedition, led the reconnaissance party through the thick woods to Moose Factory.

They returned to de Troyes in the evening to make their report, and the following day began the conquest for which they had set out from Montreal in the first place. It could scarcely have gone better. The company took Moose Factory completely by surprise, with the seventeen men inside (none of whom were soldiers) surrendering after only half an hour. From there de Troyes led the company on to take Rupert House at the eastern end of the bay. There d’Iberville distinguished himself further by leading an attack on the English ship Craven, at anchor nearby. He and his men approached the unsuspecting vessel during the night and climbed aboard: they captured it quickly and without losing a single man. From there he sailed it under an English flag to Fort Albany, the largest HBC fort on the bay, and unloaded the cannon which he and de Troyes had taken from Rupert House. After bombarding the walls for the better part of an hour, the governor emerged and negotiated surrender with de Troyes. The battle was over, and James Bay firmly in French hands.

D'Iberville had come into his own as a warrior, explorer and leader on the Hudson Bay Expedition. Though his life had been threatened multiple times during the voyage he had kept his head and braved the many trials of the merciless North. He was baptised in both fire and water, and emerged a strong and capable man, the very picture of Canadian heroism. His actions during the expedition made such an impression on de Troyes that he was left to govern James Bay after the former returned with half of the company to Montreal. Though d’Iberville left the bay in the summer of 1687, he would later return in 1688 and 1697 to successfully defend it from English attack. Most of James Bay remained in French hands until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.

The young d’Iberville went on to have perhaps the most distinguished career in service to New France of any member of de Troyes’ company. He travelled from Newfoundland to the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico, with the cannon and the compass serving alternately as his tools of trade. Despite the breadth of his voyages, it is unlikely that he ever forgot the eighty-two days he spent fighting his way through the unforgiving wild of the Pays d’en Haut, and that he remained a proud Canadian, made tough and resourceful by his battle against the wilderness, until he breathed his last.

SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

Journal de l’Expedition du Chevalier de Troyes à la Baie d’Hudson, en 1686 (French)

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville- Dictionary of Canadian Biography (English)

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville by Guy Frégault (French, 1968)

Le Moyne d’Iberville: Soldier of New France by Nellis Maynard Crouse (English, Ryerson 1958)

The First Great Canadian: The Story of Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville by Charles B. Reed (English, A.C. McClurg & Co., 1910)

Subarctic Saga: The De Troyes Expedition, 1686 by Walter A. Kenyon (English, Royal Ontario Museum, 1986)