The United States, The World Bank and The IMF: Partners In Power

Introduction

The World Bank and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) were founded at the Bretton Woods conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in 1944. These multilateral institutions wield tremendous power and influence across the world today. Indeed, depending on how you look at it, they can legitimately be said to be more powerful than most small and even medium sized countries.

The IMF’s original purpose was to maintain the newly formed fixed exchange rate system, as well as overseeing the stability of the market by assisting countries who had problems with their balance of payments position. In the beginning, the World Bank’s stated aim was to aid the redevelopment of Europe and Japan in the aftermath of World War II and to foster economic growth through lending. The two organisations were founded as the main pillars of the new American-centred, global monetary system, tasked with maintaining stability in the global economy. Over time, however, they would assume a much more imperialist role, essentially helping to build America’s informal empire around the world, a role very different from the one first laid out at the Bretton Woods conference. Ultimately, the World Bank and the IMF are just proxies for U.S. power and influence around the world.

Though the World Bank’s mission statement is full of the usual globalist slogans on “sustainable solutions”, “reducing poverty” and “sharing prosperity”, in reality both institutions are designed to regulate the flow of private capital into the U.S. and to consolidate power and influence across the world for America.[1]

That is, the World Bank and the IMF are conduits of American political, corporate and economic power which, along with other facets of the American empire, contribute greatly to finding new markets overseas for U.S. goods and capital to circulate in, to open up these markets to U.S. corporations (in particular to acquire their raw materials and natural resources) and to consolidate new capital flows into the United States by facilitating loans to lesser developed countries in U.S. dollars. Doing all of this informally builds the American empire by bringing other countries into the United States’ sphere of influence.[2]

In order to properly demonstrate all the above, I will be releasing a series of articles laying out how the U.S. accomplishes its goals using various arms of the American empire that all work and coordinate together to bring about these ends. It is important to say in advance that not everything will be covered in this article alone. This article is about organisational structure and function of the World Bank and the IMF within the American empire and how they consolidate American power overseas. Future article in this series will deal more directly with the many overseas interventions by the United States, which I plan to look at in considerable detail.

The World Bank, in particular, is largely an American creation, but in a sense both institutions can manoeuvre and operate in a way that would be problematic or politically inconvenient for a sovereign government, especially one that just happens to be the leader of the free world and the global hegemon as well. On an organisational level the Bank is dominated by the United States in terms of how it is structured, its voting practices and which policies are approved.

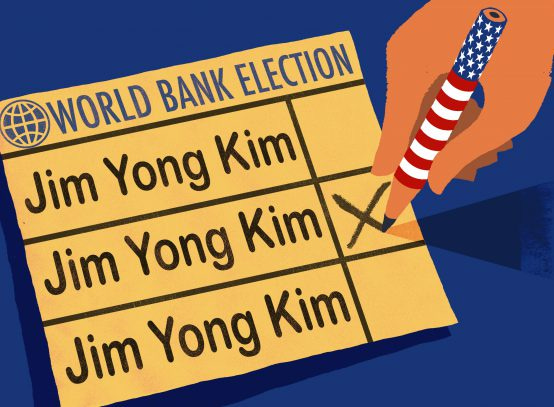

Contrary to all democratic conventions, the president of the World Bank is personally chosen by the President of the United States and there is no greater reveal as to the real intentions of the World Bank than this. The Executive Directors of the World Bank have little say in who is chosen and, whilst we can only speculate, one imagines that the Federal Reserve, the Treasury and perhaps even the State Department almost certainly do have an influence on who is eventually selected. This is because all the previous World Bank presidents have deep ties to either the U.S. government, Wall Street, corporate America, or a combination of these. The president of the World Bank has almost always been an American citizen (with one exception in 2019). In fact, it wasn’t until 2012 that a non-American had even been nominated for the position. Here is a list of the first five presidents and their respective backgrounds:

Name Background

Eugene Meyer Chairman of the Federal Reserve

John J. McCloy Assistant Secretary of War

Eugene R. Black, sr. Bank executive of Chase Manhattan

George Woods Bank executive with First Boston Corporation

Robert S. McNamara Secretary of Defence, President of the Ford Motor Company

Other notable appointees have come from Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, the Bank of America and Bear Stearns all of which are powerful banks that, it almost goes without saying, wield tremendous influence over the global economy. In one instance, James Wolfensohn even became an American citizen in order to apply for the position in 1980.(Toussaint, 2008, p.185).

Conversely, the head of the IMF has always been a European (normally a politician, central banker, or lawyer) and the IMF “number two” has always been a U.S. citizen, whose influence within the institution is highly significant.

Additionally, both organisations are located in Washington D.C., right next to the White House. Not only that, as if to underline the point, the buildings of the World Bank and the IMF are linked together by a tunnel that runs from one building to the other. John Maynard Keynes wanted the institutions based in New York and out of reach from Congress (Keynes originally wanted them based in London but that idea never came to pass).[3]

Éric Toussaint, a Belgian political scientist, believes that the U.S. Treasury is the uncontested master on board, with the power to block any change contrary to its interests. It is worth noting that the Soviet Union did not ratify the Bretton Woods agreement believing that the twin institutions were simply “branches of Wall Street”.

So in conclusion, the president of the World Bank is chosen by the president of the United States (with input coming from various government departments), it is always an American citizen who has deep ties to Washington, Wall Street and corporate America and both the Bank and the IMF are located in Washington D.C. No further comment is necessary, I feel.

For the World Bank, voting rights are determined according to how much money each member state contributes and the distribution of these voting rights determines how much relative power each member has. Originally, the distribution of votes clearly reflected U.S. and British supremacy across the two institutions: In 1947, these two countries together had over 48% of the votes. Currently, the U.S. and its allies such as Germany, France, the UK and Japan have the most voting power. On the World Bank’s Board of Governors, the U.S. is the most dominant party. The voting structure of both organisations has been revised numerous times since then, most notably to increase the voting shares of Saudi Arabia, India and China.

Crucially however, the voting structure ensures that in both institutions the United States has a built-in veto for all major decisions.[4] The U.S. has imposed an 85% majority vote for all major decisions but because the United States is the only member state with more than 15% of the voting rights they have a built-in veto and can stop the institutions from taking action that doesn’t align with their interests. Despite the U.S. voting share decreasing over time, it retains the effective veto regardless. Conversely, many of the most populous countries in Asia and Africa have little sway and influence in the Bank.

Eric Toussaint highlights that the United States has used its influence to ensure that loans are not granted to produce goods that will compete with similar goods that the U.S. manufactures and exports. This includes palm oil, citrus fruits and sugar. Loans to India and Pakistan for their steelmaking industries were reduced and the same action was taken against Mexico and Brazil’s respective steel manufacturing industries as well.[5] Additionally, loans are granted for oil drilling but not oil refining, an industry that the United States dominates.

In many ways, the relationships that the U.S. has with the two institutions is an open secret. In a book commissioned by the World Bank marking its 50th anniversary, it states that:

“The United States has viewed all multilateral organizations, including the World Bank, as instruments of foreign policy to be used for specific U.S. aims and objectives.”[6]

In 1988, in a letter to the Republican leader of the House of Representatives, President Ronald Reagan admonishes the Bank for committing funds to countries that are strategic allies of the United States:

“The Bank commits the vast majority of its funds in support of specific investment projects in the middle-income developing nations. These are mostly nations (such as the Philippines, Egypt, Pakistan, Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, Argentina, Indonesia and Brazil) that are strategically and economically important to the United States”.[7]

Source of the World Bank’s Funds

The source of the World Bank’s funds is itself a highly murky and contentious issue. Its official website makes vague claims that it sources its funds from “capital markets” and “financial markets”.[8] However, this is much of a muchness, really, because firstly “financial markets” could literally mean anything and “capital markets” simply come under the broader category of investment banking and all the major banks and financial institutions engage in investment banking to some degree or another (also, all big banks have a capital market division of some kind). The biggest investment banks are as follows:

1) JP Morgan Chase

2) Goldman Sachs

3) Bank of America

4) Morgan Stanley

5) Citigroup

And what do all these banks have in common? As you may have guessed they are all, of course, American, indeed nine of the current top twenty investment banks are American banks.[9] Thus the full network effect of all of this means that the World Bank and IMF, which are largely U.S. dominated organisations, act as intermediaries that create new channels of lending for major U.S. banks who provide loans in U.S. dollars (and U.S. dollars only) to developing countries. The interest repayments represent a parallel revenue stream for the U.S. as the debtor countries must pay back both the principal and the interest. It is estimated that between 1970 and 2007 developing countries paid $7.1 trillion in interest alone.[10]

The origins of this go back to the 1970s. In the 1970s, a series events occurred that would reshape the global economy forever. In 1971, President Richard Nixon removed the dollar’s link to gold, ushering in the system of floating, fiat currencies and as a result money creation no longer had any constraints, and this system has lasted to this day. In the mid-70s, the petrodollar agreement was ratified between the United States and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the terms of which stated that a portion of the profits from oil sales by OPEC nations be reinvested into the U.S. money markets through the purchase of U.S. debt securities via Wall Street.[11] Suddenly, all the major banks were awash with surplus dollars, this excess liquidity would be used to make loans to less developed countries with the World Bank and IMF acting as intermediaries between commercial lenders and the developing world.[12] The primary architect of this was the new World Bank president at the time, Robert McNamara; World Bank lending increased from $953 million in 1968 to $12.4 billion in 1981, as major Wall Street banks saw their Third World loan portfolios rise exponentially. A key component that enabled all of this was that the Bank and the IMF intentionally courted corrupt military dictators whom they knew would be partial to large loans regardless of the repayment terms and conditions or the long-term effects that such loans would have on the country and the people. Alex Gladstein notes that “between 1976 and 1983 the amount of IMF lending programs doubled.”[13]

It has been suggested by Alex Gladstein of The Human Rights Foundation that the World Bank acts as an intermediary between commercial lenders and the developing world but does so in a far more usurious and predatory way than one might first expect. That is, the Bank borrows from the big banks in capital markets at, say, 5% interest and lends that money to developing countries at 7 or 8% interest. On an intuitive level at least, this seems to make sense when you look at the net capital inflows and outflows into the developing world; when all the flows are totalled up the stark reality of the situation is that between 1960 and 2017 there was a net outflow of capital from the developing world, about $62 trillion.[14] So World Bank and IMF programmes provided $62 trillion of capital inflows into the developed world, it only stands to reason that the vast majority of this would be to U.S. banks.

1980 Latin American Debt Crisis

When countries take out dollar-denominated loans with the World Bank and the IMF this leaves them at the mercy of Federal Reserve monetary policy and the United States more broadly. Moreover, when the Federal Reserve raises interest rates the interest rate on outstanding loans increases as well and the consequences can be devastating. This is exactly what happened in 1980 when Paul Volcker, then the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, raised interest rates to 21 percent in a bid to end America’s long-term battle with inflation. Known as the Volcker shock, this caused tremendous economic and political damage throughout the developing world. Countries that had borrowed large amounts from the World Bank and the IMF were the worst affected as the interest payments on their outstanding loans soared. Countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Venezuela all experienced, to different degrees, severe problems to do with hyperinflation, steep currency devaluation, capital flight and crippling debt. Excessive loans from the World Bank were very much at the centre of the crisis, in the case of Brazil and Argentina these loans were made by military dictators that the U.S. had helped bring to power in the first place.[15]

When the IMF stepped in they demanded that aggressive policy prescriptions be implemented as a precondition for financial assistance, essentially these austerity programmes redirect capital and resources from the from the people to the market. Policies include: cutting public spending, privatising public utilities and social services and deregulating industry. Invariably this meant more pain for the people: UNICEF found that these programmes led to "reduced health, nutritional and educational levels for tens of millions of children in Asia, Latin America, and Africa". The policy prescriptions had catastrophic consequences: per capita income declined tremendously and both crime and poverty spiralled out of control. It led to an exodus of people fleeing Mexico and Central America heading north to the United States, a problem that continues to this day.[16]

This is what can happen when nations take on dollar-denominated debt with American lenders under the auspices of allegedly impartial, multilateral organisations like the World Bank and the IMF. This is also illustrative of the full network effect of being locked into the dollar system, something l have outlined elsewhere in detail and the dangers of a system wherein the central bank can determine the value of money, as they control both the supply of money and the interest rate, essentially by diktat. Though the role of the central banks and the broader dollar system are different topics, I wanted to allude to them briefly nonetheless as there is some overlap with the World Bank and the IMF as these organisations are, to a large degree, facilitators of this system. Ultimately, every level of this system has the imprint of the United States on it.

1997 Asian Crisis

It was a similar story during the 1997 Asian financial crisis that swept through South East Asia and South Korea. The origins of the crisis are debated to this day, many feel that it started when investors, worried that local currencies were about to collapse, pulled their money out of the Asian markets leading to significant capital flight away from the continent and to speculative asset bubbles in real estate popping. Asia was caught in a self-reinforcing vicious cycle: the more money investors removed from the markets the further local currencies in Asia declined in value, assets and investments would decline as a result and this led to foreign investors pulling more money out of the Asian markets before the cycle repeated again. In one year alone, $600 billion disappeared from Asian stock markets, GDP contracted sharply (13% in Indonesia, 6.7% in South Korea, 10.8% in Thailand) and unemployment soared (23 million people were left unemployed across the region).[17]

The IMF did not get involved until conditions had deteriorated so badly that the countries affected had no choice but to accept their terms and conditions for help. The IMF would use the crisis as leverage over the affected countries, allowing western countries, their banks and their corporations, cut-price access to their assets. Hot flows of speculative capital had caused the crisis, capital controls were the obvious answer, but the IMF refused this idea. Tariffs and other protectionist barriers were to be removed and so were subsidies, governments had to drastically cut public spending too. As a result of the IMF’s austerity measures more chaos ensued, markedly similar to what unfolded in Latin America in the previous decade. At the height of the crisis, Thailand was losing 6,000 jobs a day and South Korea lost 300,000 jobs a month, a result of the IMF’s demands for governments to cut spending and to raise interest rates.[18] People trafficking, prostitution and suicide all increased as a result. However, for Asia the pain and the humiliation was not over. As a result of the IMF’s economic restructuring policies that mandated lifting the ceiling on foreign investment and other liberalisation policies which, along with collapsing local currencies, meant that many of Asia’s struggling companies and banks were now available at rock-bottom prices. Major American banks and investment firms pounced, increasing their overseas portfolios for pennies on the dollar; AIG bought Bangkok Investment, JP Morgan bought a stake in South Korea’s Kia Motors, Merrill Lynch bought Thailand’s Phatra Securities. South Korea was hit particularly hard; Daewoo, once valued at $6 billion, was sold to GM for $400 million whilst various divisions of tech giant Samsung were broken down into smaller entities that were then sold off. General Electric, Coca-Cola, Procter and Gamble, Nestle and others all benefited from these mergers and acquisitions.[19] Public utilities were also sold off as well, all in all 186 purchases took place in the name of free trade and stabilisation policies by the IMF. As a result of the crisis, it is believed that 10,400 people committed suicide in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea (at the height of the crisis 38 people per day took their own lives in Korea).[20] Riots turned deadly in Indonesia and the Chinese community suffered the worst of the violence with around 1,200 people killed whilst Islamic separatist movements grew in parts of Indonesia and the Philippines, a result of the government being forced to reduce spending on law enforcement.[21]

The similarity between Latin America in 1980 and Asia in 1997 is striking; though the crisis in Latin America centred around loans and debt and the Asian crisis around foreign direct investment being removed the outcome and the aftermath of the twin crisis were similar: local currencies declining in value, economic contraction leading to increased unemployment and rising poverty and assets being sold off to overseas investors for pennies on the dollar with the IMF being the arbiter of all this. Far from being a stabilising institution for good, the IMF acted as a mediator between struggling nations and the banks, corporations and governments of larger nations who profited considerably from the crises.

An independent study from The Review of International Political Economy adds further evidence to the political dimension of the IMF. This study points out that, along with the 1,550 debt relief programmes provided by the IMF to its 131 member countries from 1985 to 2014, as many as 55,465 additional political conditions were attached to these programmes.[22]

Debt as Bondage

This leads us nicely to another point that should be emphasised and that is that many countries become trapped in an endless cycle of debt. The idea of debt as a means of bondage is underlined by Cheryl Payer in her book Lent and Lost, Payer says:

“at some point the borrower has to pay more to his creditor than he has received from the creditor and over the life of the loan this excess is much higher than the amount that was originally borrowed.” (Payer, 1991)

When countries are struggling to repay their debts the Bank recommends taking on new loans with supposedly more favourable terms for repayment. This form of debt bondage keeps these less developed countries firmly within America’s geopolitical orbit but causes them long-term harm in the process. Eric Toussaint says “Plainly, this was the start of the vicious cycle, where new debts serve to repay old ones, both in practice and in theory.”(Toussaint, 2008, p.145) Ultimately, the IMF ensures that countries don’t actually go insolvent: They simply take on new loans to service the old ones and the debt cycle continues.

Even Nelson Rockefeller, a former vice president, once said:

“Many of the countries are, in effect, having to make new loans to get the foreign exchange to pay interest and amortization on old loans, and at higher interest rates.”[23]

Many countries get trapped in a debt spiral when then enter into agreements with the twin institutions. That is, they need to keep borrowing from the Bank and the Fund in order to service their existing debts. There are countless examples where this has happened. A good example is Bangladesh, whose debt has grown from $145 million in 1972 to $95.9 billion in 2022, a result of having to service existing debts by taking out new loans.[24]

The Philippines is a good example of a country that became trapped in the debt spiral of the World Bank and the IMF. After the Second World War, the Philippines experienced strong economic growth and a good standard of living to match. When the twin institutions came along, however, capital controls were scrapped, the debt ceiling was lifted and president Ferdinand Marcos began ignoring the state legislature and governing by decree. Basically, the economic model that had worked so well for the Philippines had to be abandoned in order to accommodate the World Bank and the IMF. From the 60s onwards, the Philippines started borrowing substantial sums from the World Bank and by 1985 the country's total external debt was over $26 billion. After the onset of the debt crisis in the early 80s, existing debt repayments soared as a result and the Philippines was trapped in a vicious cycle of borrowing and debt that continues to this day. IMF policy prescriptions included having to float the peso, increasing taxes, cutting public spending and removing tariffs; basically, redirecting large amounts of much needed capital from the public sector in order to service existing debts. These policies had an incredibly destabilising effect on the country leading to increased poverty and income inequality across the archipelago.[25] As basic law and order gradually broke down; Marcos increasingly relied on violence and terror to silence his opposition and hold onto power.[26]

Zambia is another country that has fallen foul of World Bank and IMF policies. Being forced to remove food and agricultural subsidies has led to “stagnation and regression instead of helping Zambia’s agricultural sector.” The removal of tariffs in the textile trade has wiped out the textile industry in the city of Ndola; in 1991 there were 140 textile factories but by 2002 there were just eight. Privatisation has led to poverty, asset stripping and rising unemployment. Plans to privatise the state-owned electricity company (ZESCO) and state-owned bank (ZNCB) met with fierce resistance from the public but the IMF effectively held the country to ransom saying Zambia could lose $1 billion in debt relief if it did not go ahead with the proposed plans for privatisation.[27]

I could probably go on ad infinitum with example after example of countries who had similar experience with the twin institutions as Bangladesh, Zambia and the Philippines have had. The World Bank and the IMF see increased international movement of capital as an inherently good thing so it encourages it regardless (which is somewhat obvious as most of these inflows go directly to American banks and organisations). Ultimately, the more debt a country takes on the more dependent they become on lending institutions like the World Bank and the IMF, it is a vicious cycle.

What is also highly significant, and highly controversial too, is that a large percentage of the loans made by the Bank and the IMF are done to facilitate the extraction of raw materials by multinational companies (often American or western ones) to be exported to international markets. Loans are granted to nations who then contract large, global corporations to construct the necessary infrastructure like roads, tunnels, ports, bridges etc. that makes the mining and excavation of minerals and raw materials possible, these projects are not undertaken to improve the lives of the local people in those regions. These raw materials and minerals are needed by corporations as they are critical components for electronics, cars, consumer goods and for general consumption. In a sense, multinational corporations benefit twofold from this arrangement: construction and engineering companies are contracted for the development and infrastructure projects and then when these resources are mined they are then placed on international markets for the benefit of another group of corporations. As former President Richard Nixon once said: “Let us remember that the main purpose of aid is not to help other nations but to help ourselves.”

Catherine Gwin says that between 1947 and 1992 the United States had an outlay for the World Bank of $1.85 billion but that the World Bank made loans of $218 billion, though precise figures were (and still are) unavailable she says that it is only reasonable to assume that these loans would have generated large contracts for U.S. firms.[28]

So, in summary, the World Bank, an institution that is largely dominated by the United States on an institutional level, helps facilitate loans from U.S. commercial banks to less developed countries in U.S. dollars. These loans are then used to bring in multinational companies who extract these raw materials and natural resources for export. I don’t think I need to add much more on this.

The Twin Institutions and Dictators

One of the most salient points about the World Bank and the IMF is that they actively work with dictators across the world who are sympathetic to American interests, doing so brings these countries into America’s geopolitical domain even if supporting such regimes is clearly to the detriment of the local people in those countries. Examples of dictators who the U.S. and the World Bank have collaborated with include Suharto in Indonesia, the Somozas in Nicaragua, Mobutu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Marcos of the Philippines, numerous South Korean leaders and Guatemalan presidents too. In fact, even apartheid Rhodesia received loans from the World Bank. As we shall see in future articles, these dictators have presided over endless human rights violations including massacres, genocide, fraud and corruption, state-sponsored terrorism and even civil war. Not only have the United States collaborated with and funded these leaders, in many cases they helped bring them to power in the first place.

The inverse is also true; in many instances not only does the World Bank not assist democratically elected leaders but Washington actually works to destabilise and actively overthrow them; examples include Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala, Joao Goulart in Brazil, the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, Salvador Allende in Chile, Patrice Lumumba of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

I will be looking at these overseas interventions in considerable detail in future articles but here is an overview of some of these interventions and the role the IMF and World Bank played.

The United States sponsored a coup in Guatemala when the democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz began expropriating land held by the United Fruit Company. When Arbenz needed a loan for a vital public infrastructure project in order to help poverty-stricken labourers the Bank refused. After the CIA backed coup, the World Bank resumed lending to Guatemala during a violent dictatorship, a brutal civil war that lasted over 35 years and a genocide.

The IMF made a $43 million loan to the military dictatorship in El Salvador, not long after its forces committed the largest massacre in Central America, this massacre took place in 1981 at the village of El Mozote where the army killed 811 civilians.[29]

The World Bank suspended loans to Chile for three years when the democratically elected leader Salvador Allende was president. The U.S. helped instigate a coup that removed Allende in brutal fashion and brought General Augusto Pinochet to power, a ruler much more sympathetic to U.S. interests. Pinochet, a brutal dictator, imposed violent military rule on Chile but World Bank loans resumed during his reign regardless. Foremost among these crimes was the Caravan of Death; a Chilean army death squad that was notorious for its tactics of violence and terror towards anyone who opposed Pinochet.

The World Bank lent generously to Nicaragua under the Somozas, despite flagrant human rights violations, state-imposed terror using the infamous National Guard and widespread corruption. Between 1951 and 1956 Nicaragua received nine World Bank loans. This continued during the 1970s and, like many authoritarian countries, in Nicaragua the money was used to strengthen the hand of the repressive leader and his regime.[30] The Somoza regime’s methods include widespread torture, rape, arbitrary arrest and imprisonment and persecution of political opponents and civilians, some of whom were executed.[31]

In Indonesia, both the U.S. and the World Bank gave generously to President Suharto despite a brutal reign of domestic terror consisting of countless massacres, forced migration, corruption and genocide. It was a similar story in the Philippines where Marcos was supported by the World Bank despite a brutal reign of terror and violence.

Currently, the IMF is assisting Egyptian dictator Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who is responsible for the Rabaa massacre that killed 900 people with a $3 billion package.[32] Meanwhile, the World Bank supported the Ethiopian government that is currently committing genocide in Tigray, leading to a staggering 500,000 casualties, by providing it with a $300 million loan.[33]

Conclusion

The World Bank and the IMF help consolidate and reinforce American power across the world, significantly altering the political and economic landscape in favour of Washington. The loans that they facilitate provide access to both corporations and banks to developing markets, bringing the debtor countries into the domain of the Unites States and building the power of the American empire through both formal and informal means. This author refuses to believe that this is all by coincidence or happenstance, it is by design that all of this occurs.

Likewise, I refuse to concede that it is by pure coincidence that supranational institutions like the World Bank and the IMF, in which the United States clearly has a controlling hand in, can make loans in U.S. dollars and then have its central bank raise, purely by decree it must be said, the interest rate on those loans at a later date for the benefit of the United States and to the detriment of those countries and their people.

It is also important to understand that the broader system that the World Bank and IMF form part of has the unmistakable imprint of the United States at every level: the central bank that issues the currency, the twin multilateral institutions themselves, the commercial banks that they coordinate with and many of the corporations that undertake the projects that the Bank and the Fund design. Once again, this is by design, it has to be.

Both the World Bank and the IMF have a documented history of lending to dictators some of which I have covered here, an important issue that will resurface in future articles. It also needs to be pointed out that all of this contributes greatly to the overall liquidity of the U.S. dollar in the global economy, reinforcing its world reserve currency status to the tune of tens of trillions of dollars. Only President Jimmy Carter has ever really pushed back against the activities of the twin institutions, having suspended aid to several countries for human rights violations in the 80s. The World Bank and the IMF are just two of many channels through which the United States grows its empire. Its weapon of choice is debt and more often than not it is Washington that has its hand on the trigger.

Notes

[1] Who We Are. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/who-we-are.

[2] Prins, N. (2019) Collusion: How Central Bankers Rigged the World. Illustrated. Bold Type Books. P.6

[3] Toussaint, E. (2008) The World Bank: A Critical Primer. Pluto Press. P.45

[4] Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, Picador. P.204

[5] Toussaint, E. (2008) The World Bank: A Critical Primer. Pluto Press. P.51

[6] Toussaint, E. (2008) The World Bank: A Critical Primer. Pluto Press. P.44

[7] Domination of the United States on the World Bank – (2020). Available at: https://www.cadtm.org/Domination-of-the-United-States-on-the-World-Bank.

[8] Getting to Know the World Bank (2012). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/07/26/getting_to_know_theworldbank

[9] Wikipedia contributors (2022) List of investment banks. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_investment_banks.

[10] Gladstein, A. (2022) Structural Adjustment: How The IMF And World Bank Repress Poor Countries And Funnel Their Resources To Rich Ones. Available at: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/imf-world-bank-repress-poor-countries.

[11] Clark, W. (2005) Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar. New Society Publishers. p.22

[12] Spiro, D. (1999) The Hidden Hand of American Hegemony: Petrodollar Recycling and International Markets (Cornell Studies in Political Economy). 1st edn. Cornell University Press.

[13] Gladstein, A. (2022) Structural Adjustment: How The IMF And World Bank Repress Poor Countries And Funnel Their Resources To Rich Ones. Available at: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/imf-world-bank-repress-poor-countries.

[14] Hickel, J., Sullivan, D. and Zoomkawala, H. (2021) “Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018,” New Political Economy, 26(6), pp. 1030–1047. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1899153.

[15] Harvey, B. D. (2022). A Brief History of Neoliberalism by Harvey, David [Oxford University Press, USA,2007] [Paperback] (1st (First) edition). Oxford University Press, USA.

[16] Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, Picador. P.205-206

[17] Toussaint, E. (2008) The World Bank: A Critical Primer. Pluto Press. p.256

[18] Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, Picador. p.344

[19] Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, Picador. p.348

[20] The Economist (2017) “What Asia learned from its financial crisis 20 years ago,” The Economist, 29 June. Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2017/07/01/what-asia-learned-from-its-financial-crisis-20-years-ago.

[21] Klein, N. (2008). The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York, Picador. p.350

[22] Kentikelenis, A., Stubbs, T. and King, L. (2016) “IMF conditionality and development policy space, 1985–2014,” Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), pp. 543–582. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1174953.

[23] Toussaint, E. (2008) The World Bank: A Critical Primer. Pluto Press. P.146

[24] Gladstein, A. (2022) Structural Adjustment: How The IMF And World Bank Repress Poor Countries And Funnel Their Resources To Rich Ones. Available at: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/imf-world-bank-repress-poor-countries.

[25] Hawes, Gary. United States Support for the Marcos Administration and the Pressures that made for Change on JSTOR (1986). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25797880.

pp. 18-36

[26] The World Bank and the Philippines – (2020). Available at: https://www.cadtm.org/The-World-Bank-and-the-Philippines.

[27] Zambia: Condemned to debt, How the IMF and World Bank have undermined development (no date). Available at: https://www.globaljustice.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/zambia01042004.pdf.

[28] Gwin, C. (1994) U.S. Relations with the World Bank, 1945-92 (Brookings Occasional Papers). Brookings Institution Press.

[29] Wikipedia contributors (2022a) El Mozote massacre. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Mozote_massacre.

[30] CADTM (2019) Nicaragua 1979-2019 – CADTM. Available at: https://www.cadtm.org/Nicaragua-1979-2019.

[31] Walker, Thomas W.; Wade, Christine J. (2019). Nicaragua: emerging from the shadow of the eagle. Routledge.

[32] Amnesty International (2022) Egypt: Bitter legacy of Rabaa massacre continues to haunt Egyptians. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2019/08/egypt-bitter-legacy-of-rabaa-massacre-continues-to-haunt-egyptians/.

[33] There’s Genocide in Tigray, but Nobody’s Talking About it (2022). Available at: https://www.thenation.com/article/world/genocide-in-tigray/.