The psychopolitics of mimicry

On the destruction of the human being and the plague of identities

Recently, a TikTokker showed how limb lengthening surgery made it possible for him to go from being five feet five inches tall to six feet tall. Mary Harrington perceptively and hilariously suggests that the TikTokker in question is a male-to-male transitioner. Nowadays, as life starts to resemble performance art more and more, all kinds of people are using surgeries to change their appearance. Life is risked, sometimes lost. Limbs are risked, sometimes amputated. Of course, plastic surgery has been mainstream for a while now. But it is increasingly used for so-called gender-affirming and identity-affirming purposes. Medical science has become highly consumable; a way to signal not just that you selected your identity from a list of available options but also that you are one of the elites who could afford to do so. Is there an upper limit on what people are willing to do to alter themselves as they sacrifice themselves on the altar of self? The answer seems to be: not yet. And gender is not the only available arena within which identitarianism can play out.

Palm line surgery is now available for people who believe in palm reading but don’t like what their natural palm lines say. Add a ‘wealth line’ or a better ‘love line’ if you like. Pokertox is botox for poker players. Ear cropping, also known as elfing, can make you look like, well, an elf. Human-to-elf transitioning is now a thing. “Doctor, doctor, I think I’m an elf,” says the patient. The doctor replies, “What can I do for you today, Legolas?” If you don’t like how your belly button looks, umbilicoplasty can turn your ‘outie’ into an ‘innie’. There’s foot filling and dimpleplasty and tongue bifurcation, too. And that’s not all. It’s even possible to have surgery to permanently change your eye colour, despite the risks of severe eye damage and even blindness.

That some have assumed gender identities to be where the identitarian question or quest ends has been, it seems, rather naive. Already people have started to self-identify as animals and plants and foods. “There’s a girl on TikTok who explains very seriously that her gender is bird,” writes Mary Wakefield on this, “a cardinal specifically” with “ey/em pronouns.” Wakefield continues: “several people I’ve found identify as cake.” The bird girl, in particular, apparently experiences gender dysphoria around her mouth because birds have beaks. Anyway, what is perhaps most difficult to understand is why any of this is happening at all.

The obvious answer is that it’s complicated. What isn’t complicated these days? But, no matter the complexities and the genealogical ups and downs and detours, I think it’s possible to offer a fairly straightforward answer even if it requires a little explaining. The answer is this, and the explanation is below:

When people no longer have any metaphysical grounding, they become subject to mimetic desire alone.

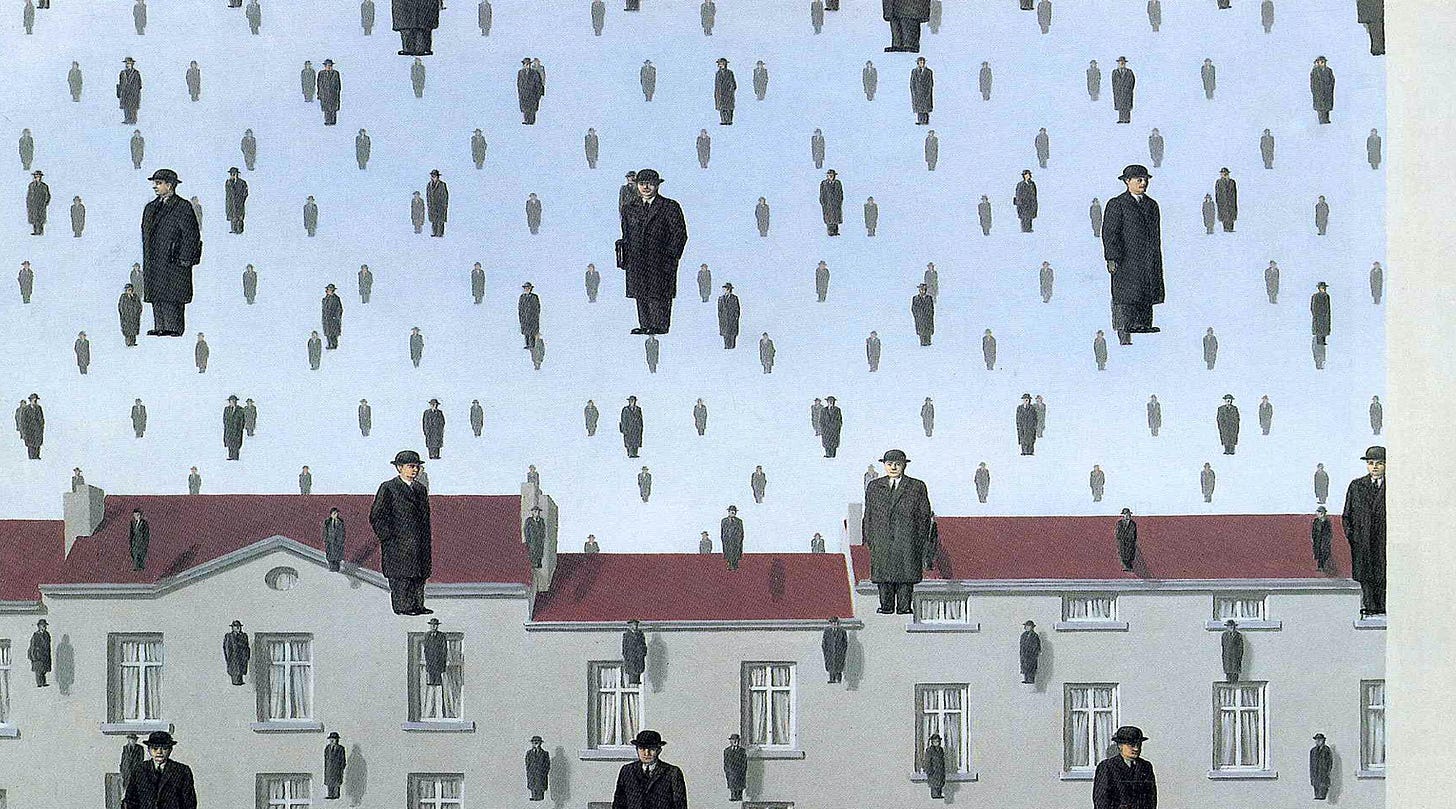

In other words, identities gather like flies around the recently murdered corpse of essential personhood. Here, then, is an attempt to explain the plague of identities with reference to mimetic psychology. I am well aware that mimetic psychology doesn’t explain everything but what it does explain is worth our attention.

To understand the identitarian phenomenon as social currency and social contagion, we must pay close attention to the question of desire, especially unconscious desire. As Pablo Bandera writes, “It is irrational to consciously desire something that will do us harm,” which is what identitarianism often leads to, “but a latent mechanism hidden below the cognitive radar of conscious thought, and rooted in causes that occurred perhaps years ago, need not be rational with respect to what is desired now.” Desire is not merely appetitive. It “should be understood in the broader sense as that which motivates attitudes and actions in general. My desire is not merely a statement of what I want but why I want it and under what conditions that wanting is created and sustained.” Desire precedes motivation and action. It shapes our emotional states and directs our lives.

It’s always been a temptation to think of desire as an individual thing, just as it’s always been tempting to think of identity as an individual thing. However, in modernity, this has been mistaken as the only way desire works. Liberal moderns assume that we can attribute desire to autonomous individuals who operate autonomously. And yet the blatantly non-individual character of identitarianism in all its forms is there for all to see. Socialisation and over-socialisation are inescapably part of this, especially considering that in a previous age declaring yourself, in all seriousness, to be a bear or a leopard would have landed you in a looney bin. Now, it is almost considered pathological to suggest that your given humanness is ontological and that your biological sex, for one thing, is permanent. Identitarianism is so tribal that the derivative nature of identity and the desire that sustains it should be obvious to everyone.

This proliferation of identities would never have taken root if it hadn’t been for the way personhood became rationalised, and thus not just misunderstood but in fact obliterated, by the myth of the atomised self. The myth was formulated at the start of modernity. And, as Michelle Schumacher argues in her book Metaphysics and Gender (2023), the myth has become further entrenched through the reversal of an old metaphysical formula. The ancients believed that essence, meaning the nature of being, precedes existence, meaning the fact of being. This is an echo of another formula, which holds that actuality precedes and conditions potentiality. The common sense idea holds that things have natures that govern what’s possible. But Jean-Paul Sartre articulated and advocated for inverting the old doctrine and famously proposed, specifically with regard to people, that existence precedes essence. He may have just been wording the Zeitgeist but, anyway, the idea stuck.

He suggested that the fact of one’s being (existence) is more significant than the nature of one’s being (essence). To support this inversion, he had the help of some friends, including fairly large quantities of irrationalist voluntarism and nominalism. You would need the world to become discarnately digital, too, to prevent physiology from announcing itself too loudly in opposition to the voice of the unworlded purely psychological self. It’s much easier to proclaim that you self-identify as the square root of thirteen if you aren’t quite attached to your body. Unfortunately, there was and remains more than enough of all of this to help the speculative grifting of identity ideologues.

With the Sartrean inversion in place, a number of other inversions become possible. In ethics, the subjective usurps the objective and personal preferences undermine any shared ethos. Self-interest becomes more important than the common good. In language, you may as well spell words any way you want because how you use language can be entirely up to you as an individual. In artistic creation, notions of standards of excellence can be discarded. In general, in fact, standards are thought to be worryingly totalitarian. In the realm of epistemology, desire can become more important than understanding, which is what the trans movement’s phrase ‘my truth’ ultimately means; it means that essence, which is known, is entirely subservient to existence, which is wanted. Several other things are upturned as well: ideas negate reality; gender usurps sex; culture supplants nature; and creatures displace God. In short, the given is rendered if not irrelevant then certainly pretty close to unimportant. Theory and personal opinion are, for conscious and unconscious Sartreans, more real than reality.

The general acceptance of the overthrowing of essence by existence means that one has to achieve one’s own being. As Byung-Chul Han argues, our very understanding of freedom has been so eroded that our subjectivity no longer means being subject to anything; it means, rather, that subjects must make themselves. The subject becomes a project. We must all be self-made men and women, even if that means being made-up men and women. We no longer require systems to exploit us since the goal of self-creation has become so ingrained that self-exploitation is now not just normal but advisable. Today, everyone is an “auto-exploiting labourer in his or her own enterprise.” As Han writes,

“Today, the distinction between proletariat and bourgeoisie no longer holds … Literally, ‘proletarian’ means someone whose sole possessions are his or her children: self-production is restricted to biological reproduction. But now the illusion prevails that every person—as a project free to fashion him- or herself at will—is capable of unlimited self-production. This means that a ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ is structurally impossible. Today, the Dictatorship of Capital rules over everyone.”

So, form follows funding. Money reigns over nearly everything as the goal and enabler of total self-redefinition. Only the rich or those who grow up in wealthy societies can surgically alter their bodies to fit the picture they have in their heads. The plague of identities is most pronounced in countries that are very well off. To reference Baudrillard’s observation, the problem is American; and because America is the heart of the media engine, the problem is now everyone else’s as well.

But only the privileged, shielded from the real by simulacra, can wrap themselves in the illusory surface of another body’s appearance or declare themselves to embody the spirit of a wild cat or an ogre. Poor kids in Africa aren’t lurching at every opportunity to don imaginary labels. “Obey your thirst,” said the old Sprite commercial. “Obey the surface,” says elitist liberalism now. The social conditions established on the basis of modern individualism are set up, as Charles Taylor argues in his A Secular Age (2007), such that no belief is adopted naively, not even belief in the inalterability of your own biology. A recent article I saw declares that ageing is natural but soon we may even treat age as a disease. Every belief, even the belief in the human as such, can feel optional in our time. In keeping with the ideology of self-manufacturing, belief is now guided by little more than a flimsy sense of preference.

All of this is a mythical construction. The myth of modernity is the myth of the atomised individual. I use the word myth here to mean that the whole thing is a coverup for a deeper and much more sinister set of happenings. The modern myth is brilliantly symbolised in H. P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror, especially in how he sets up a radical gap between the isolated self and a sort of awe around the Elder Gods. He suggests a reality in which the individual is absolutely and radically alone; and thus, in Cartesian fashion, incapable of communion with the other. The other shows up as something horrific. Otherness is so overwhelming that it can drive the individual to madness.

This reveals that madness is already so embedded within the Cartesian ego that a person can declare ‘my truth’ without having the vaguest notion of the truth. To assume such detachment from worldly existence is already insane. It is insane because it isn’t true. It is a mythical coverup, among other things, of the fact that personhood is essentially non-individual. No amount of existence-preceding-essence-propagation can undo this fact. It is only by understanding the non-individual character of personhood that we can properly understand how the notion of the individual conditions a plague of identities. Note, some of the identities available are not necessarily going to be contagious. Very few people are likely to want to identify as a dragon, for example. But the fact that identity can be entirely elective is nevertheless contagious. Add rivalry to the mimetic contagion, and soon electing a uniquely different identity becomes a command.

In practice, none of this makes people freer. Just because we can and therefore somehow must make things up as we go along, means that there is no given order to meaning. Personhood is not even considered in terms of lower, middle and higher faculties as both Plato and contemporary neuroscience suggest. Wisdom is scapegoated and the result is a world of whims and urges coagulating around fashionable declarations of unbridled egotism. We shouldn’t be surprised, perhaps. Think of the classic interpretation of our age by Jean-Francois Lyotard; postmodernity means incredulity towards metanarratives. But incredulity towards metanarratives simply ends up in excessive credulity towards micronarratives. When the given is not taken as the source of meaning, we must look for meaning elsewhere. And where do we look? To each other, of course. But to understand this more fully, we need to have an understanding of how desire works with regard to the other. We need what René Girard and Jean-Michel Oughourlian call a mimetic or interdividual psychology, which describes the modern proliferation of identitarian crises better than most other paradigms. It explains why we want what we want and under what conditions such wanting is created and sustained.

Human desire is not autonomous. A person “cannot draw his desires from his own resources,” says Girard; “he must borrow them from others.” Desire does not spontaneously arise within us but is mimetic. Desire is mediated by and through the very other that has been designated as irrelevant to the modern self. This simple idea wrecks the usual understanding of desire as having a linear structure, with a direct connection between the desiring subject and the desired object. In reality, desire has a triangular structure. It exists between the subject, the model, and the object of desire.

We have basic biological needs and urges, of course, but mimesis transforms these. I need to eat, for example, but my desire is mediated to suggest that I should eat certain things rather than others. If I am thirsty, I need water. But mimesis might suggest that I need Perrier or Evian. While there are complexities to this process, the basic premise holds that even if unmediated appetites exist, unmediated desires do not. Nothing you want is yours to want alone. The idea of absolute self-determination is absolutely wrong. This much should be obvious, for example, simply in the fact that so-called gender transitioners affirm the gender binary. What they are emulating is absolutely clear to everyone, including themselves. Desire means mimicry. Psychopolitical desire means mimicry on a large scale.

Mimetic desire is at work in even the most commonplace of human actions. Take the simple example of a handshake. Two men meet up. One of them holds out his hand and the other imitates the same gesture. They shake hands and this establishes that both of them, in this reciprocal mimetic action, are on good terms. It takes no effort to see that this little social interaction is mediated by tradition. Somewhere along the line, the gesture was developed as a way to say, “Look, I don’t have a weapon in my hand. I’m not here to hurt you.” In this action, mimesis is a positive force. It is the foundation of positive reciprocity. But mimesis can be a negative force as well. Rivalry, and even vengeful animosity, stems from mimeticism as much as friendship does.

Mimetic desire is a theme with myriad variations. It can be gentle or ferocious; it can bring people together and drive them apart. As Oughourlian writes, “desire is always, in variable proportions, a cocktail of complicity, attraction, affection, and love on the one hand, and of rivalry, repulsion, and aggression on the other, and the latter can reach extremes of hatred and violence.” Nevertheless, whatever the shape of mimesis, personal desire is always saturated with otherness. To be in the grip of desire is to be bound to the other through whom our desire has taken shape.

A good example of someone who gets extremely close to seeing the truth is found in a post by a nameless Redditor. The post was filed under the question, Can you suddenly become transgender? After learning of a certain influencer who was undergoing hormone replacement therapy, the Redditor “got a sudden signal” from their brain saying, “You’re trans now.” The Redditor goes on to explain this as follows:

“The thought has been haunting me since that moment. I don’t know what to do. I never had any thoughts on the topic before, I’m pretty progressive and watch progressive content creators and have many LGBT friends, trans people included and have listened to podcasts with trans people as well, etc. but I never had such a thought and felt pretty good with my body and who I am. I don’t feel good with this idea, I don’t feel like it’s ‘mine’. It feels like an alien body taking over mine. Has anyone felt like this before? I will be very thankful for your help.”

In this specific case, mimetic psychology really can help. Arguably, the person here has discovered the truth of mimetic desire but not a way to articulate it. It is a desire shaped by a general field of social contagions within which he or she is totally immersed while experiencing it still as alien. A similar idea might apply to someone who claims to be an animal trapped in a human body. It might even apply to someone who claims, “You know, I’ve always wanted to be a banker!” The desire is experienced as if it is his or her own desire and yet there is, on closer inspection, something odd and alien about it.

The ideology of can, described by Han, gives rise to a seemingly inescapable must. No thought is given to the possibility that acquiring a desire, via mimesis, leaves the person with a choice. Actuality is gone, so the dictatorship of potentiality becomes (nearly) everything. Note the implicit denial of psychological depth. Note, too, how conformist and shallow the impulse is here. This, in fact, is one of my main concerns with the way mimetic desire is so commonly styled in our time. We are made for a rich and expansive life but the general ideological frame of our time suggests that our desires should be cut down to a more politically correct size.

What I want to stress for now is the role of capital in structuring our mimetic relationships. Liberalism and capitalism exist in a thoroughly co-dependent relationship. This is most evident in how the cultural openness of American leftists conspires with the market openness of American rightists as two sides of the same thing. On the side of the liberal left, all common relationships and bonds are actively attacked and even obliterated. On the side of the liberal right, the resulting fragments are picked up by capital and reconstituted in the image of whatever happens to come to mind. Woke capitalism is an apt name for this collusion. Commonly, leftists, in the throes of psychological projection, see how capitalism is a problem. But they fail to see, generally at least, that their own approach to destroying the given is what allows capital to gain ground. They fail to notice, therefore, that the myth of the individual is at play, building reality bit by bit, one consumable fragment at a time. Meat-Lego becomes easier with money reinforcing the myth of the atomised self. Well, the old name for money or capital is Mammon.

In his sermon on the mount, Jesus explains that you can’t serve two masters. You will either serve God or Mammon. The latter word came to be associated with a pagan god, although this may have been an error. Maybe Jesus just meant wealth and not some weird deity but what remains significant is the essential opposition. There is no third option; no middle ground. Either you accept that essence precedes existence or you end up believing that existence precedes essence. Either you accept that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts or you attempt to strive for make-believe wholeness by constructing a world out of bits and pieces. And if you side with the latter, you inevitably side with money.

Money has no being, no essence. The history of money is, in fact, a history of a thing becoming increasingly detached from any essential, usually material, reality. It now ‘exists’ mostly as data; its apparent ‘reality’ is determined by mimetic agreement alone. We ‘make’ money because its existence precedes any essence. Divorced from essence, it perpetuates the idea that untethered desire is all you need. If you have the money, you can do whatever money will allow you to buy. You can place your body onto the altar to the gods of the medical-industrial complex. On that altar, your former self can die and a new self can be resurrected. Is this not the materialist version of being born again? Salvation by memes.

As Girardian thinker Jean-Pierre Dupuy notes, “One cannot make money by going against the [mimetically constituted] crowd.” Recently, as Hannah Barnes examines in her book Time to Think (2023), about the catastrophic failures of the Tavistock Clinic’s Gender Identity Development Service for Children (GIDS), it became clear that money played the largest role in perpetuating risky treatments that had no basis in reality. The science was shoddy; the evidence of the effectiveness of so-called gender-affirming care was non-existent; the issue of what was ultimately best for those who came knocking at the Centre’s door was irrelevant. As Barnes notes, doctors couldn’t really answer whether they were “treating children distressed because they were trans, or children who identified as trans because they were distressed.” Camilla Cavendish writes for the Financial Times, “This lack of interest seems to betray a wilful failure to safeguard the wellbeing of the children involved.”

Willful failure seems like the understatement of the century but it is perhaps what we should expect given the state of global culture. Society, devoid of any given hierarchies of meaning and ethics, has agenda dysphoria. When no one knows what’s worth emulating, anything might be emulated. All forms of identity-mongering and identity-fundamentalism seem to indicate widespread and ever-increasing social instability. Identities may often be attempts to anchor the self in a constantly fluctuating world. If you’re lost and confused in all other respects, at least you can be sure of something that is yours. You made it, or so the IKEA-effect of identity politics will have you believe. But, actually no. You didn’t make it because desire is mimetic, copied, or borrowed. Sometimes, perhaps too often, desires are emulated that do not have any deep rationality behind them. They answer a question, although not nearly as well as the question can be answered. But to better understand how mimetic desire works, we must have a sense of the dynamics of the one desire that rules them all, which Girard calls metaphysical desire.

In Deceit, Desire, and the Novel (1961), Girard claims that all mimetic desire is, at its root, metaphysical desire. This means that every mediated desire—large or small and to lesser or greater degrees—is ultimately subservient to a larger, controlling desire ‘to be.’ Overtones of Spinoza’s conatus essendi can be found in this, with the basic principle being that we don’t only want to keep existing but also want to enhance our existence. We want ‘to be’ but also ‘to be more.’ The insight Girard adds to Spinoza’s idea is that desire endlessly plagiarises the desire of another. Even our desire ‘to be’ is not entirely our own. We might say that metaphysical desire is a desire to possess something of the very existence of the other. Taken to the extreme, it may turn into the desire to possess not just something of the other but the very being of the other. Metaphysical desire at its most potent frames the other as a rival to be contended with or as an obstacle to be replaced.

Metaphysical desire is sustained by the natural sense that we are not, in ourselves, complete. We lack being. This does not mean, however, that we are this lack. After all, to feel lack is to possess a measure of being. If I feel hungry, for instance, it is because I have sufficient being to be able to experience the feeling of hunger. But I still feel that I am not self-sufficient. I rely on what is not me for sustenance. We can mistakenly over-identify with our sense of lack, though, such that a question of a passing desire being met or contradicted can turn into an issue of identity. A person mistakes the lack for who they fundamentally are and is therefore set up to regard the answer to this lack as absolute.

This is to say that sense of lack can be transformed by the current expressive individualism of Western culture. The focus becomes manifesting one’s own self-manufactured sense of authenticity as compensation for lack. This will always turn out to be thought of in the midst of a plague of plagiarisms. Have you ever noticed that those quickest to claim their originality are also the most likely to hold the most average views? You might think that someone identifying as some other animal or plant would be original, for instance, but it turns out that they’re often oddly committed to the status quo. The neuro-divergent students I’ve taught who over-identify with that label are often the most easily duped by the ideological norm. They are conformists par excellence. The invitation to authenticity often opens the door to banalification. All of this is owed to metaphysical desire.

Metaphysical desire can bring peace and harmony. People grow up with heroes they want to imitate, for example. Aspiring to possess something of the being of a mimetic model can be profoundly enriching. This is how we learn. Rivalry between subjects and their heroic models is impossible when two things are in place, namely hierarchy and a sense in people that what they are co-desiring, such as a virtue or some other spiritual quality, is really infinitely sharable. There is no shortage of goodness and love, for instance, which are manifest in so many things and in so many ways. However, where hierarchy is destroyed and where the objects of desire are in short supply, rivalry is rather likely.

This, we should notice, is precisely what has happened in modernity, which is virulently anti-hierarchical and materialistic. Money comes into this again. What is worth purchasing is heavily dependent on what is popular. If tattoos are popular, you are likely to want a tattoo just like your friends. If your peers have enough money to get certain medical treatments and enhancements, that’s what you’ll likely want. The potential is presented to the auto-exploiting subject/project as a solution to that sense of a lack of being. What is on offer may not be the actual solution to this lack, of course, but where existence has usurped essence, the question of an actual solution is not generally asked. The dictatorship of relativism holds that if you would prefer to have healthy parts of your body amputated, who is to say that this is really a bad idea?

If we take metaphysical desire as the archetype of all desire, we should notice that it always involves interpretation. Yes, a desire is copied from the other. But it is never an exact replica of an original desire. It is filtered through the person doing the copying. As Oughourlian says, “if interdividuality determines the psychological and psychopathological destiny of human beings, those human beings nonetheless enter into a mimetic relationship with a particular history and structure.” Different people respond to different mimetic inputs differently. The process is analogous to that of a number of artists all depicting the same object at the same time. The result is not several identical works but several non-identical repetitions. Each artist imitates the form of what they are depicting in a unique way, with imitation being a process of adding and subtracting and translating. Gains and losses in the negotiated meaning of any emulated desire are similarly inevitable.

One can aspire to the brilliance of a hero while fully recognising one’s limits with regard to achieving the same greatness they have. The right interpretation of our own metaphysical desires should involve certain metaphysical commitments, including a commitment to be true to the specifics of our own lives and our own embodied limits. However, if metaphysical commitments are done away with, whether consciously or unconsciously, the Barbie-esque tagline becomes fully operative: “You can be anything.” In other words, as you ‘produce’ the ‘product’ or ‘brand’ of yourself and/or your identity, any limits in actuality can be ignored in favour of potentiality. Real limits don’t go away, of course, but what is ignored becomes as good as irrelevant to the identity manufacturer.

This is another way of saying that we can and often do misinterpret the desires we copy, just as we can often misinterpret our own desires. We can mistake bad desires for good ones just as we can mistake unattainable goals for attainable ones. Inevitably, misunderstanding will be at work in desire. Our perceptual capacities are creative, after all, and not merely receptive. Moreover, we tend to forget that our desires are derived. Often, in the very moment we take on the desire of another, we assume that it is our own desire and not theirs. There is some good in this. By taking on the desire of the other as my own, I am able to act in my own capacity. I am responsible. Still, the derivative nature of my desire is by no means thereby eradicated.

Adapting and adopting the desire of the other creates a new self. This helps us to take on different roles in different environments and surrounded by different people. We contain multitudes if only potentially because we can emulate so many different others. This is the crux with regard to metaphysical desire. The new self shows us that we take on as an issue of identity what emerges, always and everywhere, within the complex play of differences. We care, to use Heidegger’s notion; we take a stand on being on the basis of mediated desire. Whatever meaning we understand is not solipsistically created by us but is, at the very moment it is experienced as meaningful, suggestive of communion with others.

Play, it turns out, is vitally important for healthy desire. Psychologically healthy people tend to derive their own world of desires from multiple models. They also tend to have a definite sense that their own desires are copied, or at least part of a shared world of desires. One example is found in how St. Paul didn’t mind at all when he asked his audience to imitate him as he was imitating Christ. It is a common refrain in wisdom literature to know who and what you’re imitating. Notice where the desires of others are good and then, please, plagiarise with joyful abandon! Part of this healthy way of desiring is an acute sense that others will make up for our own deficits. We do not have to be all things to all people. In healthy desire, there is no envy since gratitude for the given overcomes any sense of lack.

But unhealthy desiring is another thing. Envy takes root, as does pride. The sin of covetousness addressed as the last of the Ten Commandments becomes a priority. The copied desire is interpreted in a distorted way. As metaphysical desire intensifies, desire reifies. A person then starts to fixate on the model’s desires in a way that suggests a false ideal that desire should be copied to the extreme. The self, created by the evanescent desire of the other, is interpreted as something that must be rendered permanent. The desire must be fully embodied.

It is possible to think, for example, of how Nietzsche came to see himself as embodying Dionysus and, which amounted to the same thing, the Antichrist, who opposed Christ. The terrible irony was that he failed to see that Dionysus was not the spirit of the aristocrat that he so wanted to be but the spirit of the mindless, scapegoating mob. In the end, Nietzsche could not settle with being slightly at odds with Christ as his rival; instead, he felt that he had to oppose Christ absolutely. It was not good enough, in his view, to simply copy aspects of the Dionysus cult. He had to become Dionysus. Nietzsche was trans. He was a man-to-god transitioner or man-to-Antichrist transitioner in much the way that Andrew Tate or that stretched-out-guy I mentioned earlier are male-to-male transitioners.

Some people are human-to-banker transitioners. Others are human-to-alcoholic transitioners. Identity-fundamentalisms of all kinds are possible in an age in which the human is essentially contested. History repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as LARPing. And yet the people taking on fake identities do not even have enough of a sense of humour to notice that they’re faking. It is possible, as I am suggesting, to imitate the desire of another with such force that one becomes a fundamentalist with regard to one’s own identity. The more rivalry there is, the more likely this becomes. The more rivalry, the more of an identity-fundamentalist or identity-evangelist one is likely to become. The best way to confirm an illusion, after all, is to get others caught in the mimetic contagion to affirm it. Get some support, even if you have to get it by throwing your toys out of your cot.

Now obviously, there are aspects of ourselves that are more or less stable but it is possible that certain ways of desiring and certain specific desires become far too rigidly fixed when they ought not to be. The forgetting of the otherness of desire that is arguably necessary for allowing each person to take responsibility for their own choices soon turns into a harmful possessiveness over the desire that is subsequently assumed to be, to borrow from J. R. R. Tolkien’s uniquely jealous little slime-hobbit, “my own, my precious” desire. The ancients had a word for this. They called it idolatry. Now we have other words, like obsession, fixation, and addiction. But it seems to me that idolatry is the better word because it connotes substituting a much lower state of being for a higher one. The relative becomes a shoddy replacement for the absolute.

In this idolatrous state, this mode of desiring becomes wrongly fixed, and rivalry becomes increasingly central to the desire of the envious and jealous. Oughourlian points out that “desire appears to be triggered and reinforced by prohibition, while in reality it is mimetically consubstantial with rivalry. Prohibition is but the manifestation of the power of the rival who forbids the object.” To be clear, then, rivalry stems from a shared desire, not from different desires in conflict. Rivalrous people are at odds with each other not because they want different things but because they want the same thing. But in wanting the same thing, difference is exacerbated and soon becomes exaggerated. Binding similarity produces excessive differences. Rigid similarity encourages rabid polarisation. How might one radically differentiate oneself from the other in the midst of what Baudrillard called the hell of the same? The answer: emulate and manifest the extreme opposite of what one is simply to one-up the rival.

The object of desire in this growing obsession with difference—the seeming goal of all the desiring—is often arbitrary. It has no value on its own except as a manifestation of rivalrous mimetic desire. When two people or groups copy their rivals with ever-greater intensity, what sustains the rivalry is not the object of desire—say, Helen of Troy in the Trojan War—but the rivalrous desire itself—the enmity, in this example, between Greece and Troy. At its most intense, metaphysical desire has no object but the rivalry itself; that is, with outdoing the rivalry of his rival. What is especially hazardous about this is that anything can happen. People can get badly hurt in all kinds of ways when rivalry becomes so embedded. This is the ongoing temptation for political absolutists who find themselves unwittingly picking a side not because it fits their values but because it is simply the best shot they have at opposing a side that repulses them, and which they are secretly attracted to. I’ve heard election analysts point out how often their predictions of who will win depend most on just how unpopular their main rival in the running is.

One example of a rivalry that causes tremendous harm to desiring subjects, an example offered by both Oughourlian and Girard, is that of anorexia. As Oughourlian writes, “No man finds a skeletal woman attractive, but [anorexic] women don’t care: they are seeking not to conquer a handsome man but to outdo their feminine rivals in skinniness.” He echoes Girard who writes the following, “Anorexic women are not interested in men at all; not unlike these men, they compete among themselves, for the sake of competition itself.’” The anorexic’s dysmorphia is analogous to gender dysmorphia in that her desire is undeniably at her own expense.

Lionel Shriver rightly sees a strong resemblance between anorexia and the trans phenomenon, rooted in an observation of mimesis: “Both neuroses are clearly communicable.” The essentially competitive nature of the anorexic’s desire means that she will quite willingly sacrifice herself on the altar of rivalry. Here we have a crucial insight not just into the trans phenomenon but into the current pandemic of sexualities. Many know this already, such that what I am about to say will not be at all surprising. Still, it must be said. The entire ideological parade has nearly nothing to do with sexuality and everything to do with rivalry. There is no getting away from the fact that gender ideology manifests everything that Nietzsche and Max Scheler have said about ressentiment. The ideology is rooted, not in positive values, but in an attempt to forge positive values out of negative reactions.

Keeping in mind what I have said about the general irrelevance of the object of desire, one of the strangest facets of rivalry is that when a person acquires what they thought they wanted, they often feel an overwhelming sense of disappointment. This is echoed in the story of Daisy Chandra, who by her own admission has an issue with envy. She explains that when she finally completed her transition, she felt immense dread; and the thought of suicide came up for the first time for her. She got what she thought she wanted and then discovered that she didn’t want it after all. She had acquired her desire and had felt only loss. This is not an uncommon occurrence with non-integrated people. Desire, especially when bolstered by rivalry, tends to fail precisely when it succeeds. It vanishes just when the person possesses the thing they coveted.

As Girard writes, “The disappointment is entirely metaphysical. The subject discovers that possession of the object has not changed his being—the expected metamorphosis has not taken place … The object never did have the power of ‘initiation’ which he had attributed to it.” When desire disappears, when there is no desire to imitate and no possibility of rivalry, depression sets in. One becomes, as Oughourlian writes, “inanimate” and “psychologically numb.” This may be one reason why people who have fought for equality and then achieve it will keep fighting for it as if they are still profoundly oppressed. The victory cannot be acknowledged because to acknowledge it would be to lose any reason for existing. The self, formed in mimetic rivalry, would cease to exist.

Our happiness, by being tied to our mimetic desires, is precariously bound up in the lives of others. Wholesome relationships mean sharing desires. As Girard says, “To imitate one’s lover’s desire is to desire oneself, thanks to the lover’s desire.” We feel ourselves worthy of love when we see ourselves through the eyes of another. Breakups and deaths or simply separation are terribly difficult things to deal with because what is lost is a sense of oneself as lovable in a certain way. The end of any relationship means, among other things, the end of a certain self-created by desire. We are never just left to mourn the loss of the other, then, but are thrown into grief at having lost a significant aspect of ourselves.

This sense of a certain self is, however, also present in unwholesome relationships. It is not just people who get out of good relationships that find themselves wondering who they are; people in bad relationships experience the very same struggle. It is one reason why some relationships persist despite being so terrible. The question will be asked, if only implicitly: Who am I if I am not at odds with this person I am with? The mistake, however, is to assume that you are only one thing. And yet, strong rivalries function like enchantments, telling a person that this self is the only one she has and without which she is nothing. The truth would be otherwise: you will find other ways of wanting and being. It is possible to be integrated.

With rivalrous desire, just as much as there might be a command to imitate the desire of the other, there is often also a prohibition. As metaphysical desire intensifies, the unhealthy desire tends to have these two commands at work simultaneously. The prohibition reinforces the command. This is strikingly shown in a post I saw trending recently. On social media, a young man had written the following, accompanied by a photograph of himself looking decidedly feminine:

“24 years ago when I was 8 years old, I played [and] made flower crowns with a girl named Erin. I got teased badly and remember wanting to be her so badly. 24 years later, I am Erin. And I’m rocking my flower crown.”

Here we have, like a tiny superhero origin story, all the tell-tale signs of a pathological metaphysical desire. The young man, when only a boy, was just enjoying an activity with a friend. But the activity was strongly prohibited by others around him, who mocked him to inform him that what he was doing was not acceptable. What is not explicitly said but is no doubt a component of this origin story is that the original Erin was not as tormented as he was. She was free ‘to be’ in a way he wasn’t. He quickly interpreted her as being equal to the idea of existing in greater measure. In the perfect storm of prohibition and metaphysical desire, a fixation arose. Erin had what he didn’t have. And so the young man elected, eventually, to adopt the identity of the girl he was playing with 24 years before. He had a conversion experience, perhaps; he was born again, by his own supposed self-determination, as someone else. “I am Erin,” he says in his post. By announcing his identity, he inadvertently announces that the desire he had to be Erin was never his own.

But whose desire was it for him to become Erin? Did Erin want him to be like her? It is terribly unlikely that this is the case. Would Erin have wanted him to plagiarise her entire identity? Certainly not. We have, in fact, to look no further than the rivals for the source of the desire to be Erin. The bullies are the reason that he wanted to enhance his being. The object of desire could have been almost anything but Erin just happened right there, probably as the unexpressed but implied desire of those very rivals. “I got teased badly,” he says the Erin-wanna-be, “and [I] remember wanting to be her so badly.” In rivalry with the mockers, he elected the most dramatic way possible to distinguish himself from them.

Such rivalry is common enough among transitioners. One example is of a man who sees himself as a crippled woman. He underwent gender reassignment surgery and spends his day going around in a wheelchair. The latter is an addition to his supposed identity as a woman, apparently, since he is not, in actual fact, crippled. He can walk. This is scandalous but why it should be more scandalous than his desire to be a woman is beyond me. The scandal is divisive only because everyone’s mimetic desire is cast into sharp relief. It is my contention that the only way to understand any of this is by seeing how metaphysical desire and rivalry are at play in it.

Still, to get back to that earlier example, I can imagine someone saying to my assessment of the case of ‘Erin,’ “But that can’t be right. The scoffers and mockers didn’t want him to literally become a girl.” What is crucial here, however, is the role of mediation in desire. If a parent tells a toddler, “Don’t look in that cupboard,” the literal command is not the only thing at play. The toddler is likely to imitate the desire behind the command—the desire to be in charge of the cupboard. That is the point in all rivalrous desires. The issue is not the object as much as control. If some boys mock a slightly effeminate boy, the implicit issue at play is that they are taking charge over what is and is not permitted and it is this desire that ends up being imitated. In this rivalry, he fixates on Erin as the goal of his desire to enhance his own being and thus maintain control. Unconsciously, he may have wanted the affection of those very rivals. The fact that the medical-industrial complex supports this in the name of compassion is an attempt to mythologise metaphysical desire and its resulting violence. It covers up the fact that the motives behind all of it are not pure.

I would be extremely wary of universalising any of this, though. Gender dysphoria may emerge for all kinds of reasons, some of which would be neurological, and no doubt the lens of mimetic theory is not going to expose all of them. But what is inescapable in our time with regard to the transgender contagion is that the phenomenon of people declaring themselves as trans is bound up in rivalrous desire. This causes suffering on all sides. What is interesting to me, however, is that often the person whose desire is sick is assumed to suffer the least when clearly they suffer too, not from not being affirmed enough but because their desire, so distorted and disproportionate, is set against their own bodies. They cannot reconcile themselves to the otherness of their desire and so they seek to fully embody that otherness. They cannot reconcile themselves to themselves and so they demand to be someone else, even if that means becoming subject to unnecessary surgeries that, contrary to popular belief, diminish their being rather than enhancing it.

The old mantra of medical ethics, “First, do no harm,” has been replaced by a new ethos that encourages certain forms of illness because they are markers of that most idolised idol of modernity: identity. No one would contest that something is wrong if a woman becomes addicted to plastic surgery that increasingly distorts her appearance to the point of grotesqueness. Why is it then acceptable when people undertake surgeries to modify their bodies in other often more dramatic ways? Well, the answer is not rational. The answer is in what people have agreed to. The mimetic consensus gets to call the shots. Of course, some of the identities I have named seem somewhat harmless. But I would argue that in their denial of any human essence, they are co-participants in very real harm done to real people.

There is, it turns out, nothing in the ideology itself that would stop doctors from later paralysing patients who self-identify as crippled and blinding patients who self-identify as blind. Actually, with regard to the latter, such a thing already happened a few years ago when a woman who was convinced she was disabled despite being fine got a sympathetic psychologist to pour drain cleaner into her eyes to blind her. It is a strange thing when something, typically taken as a lack of being, is envied. The point is that metaphysical desire itself does not place any limits on what might be envied and emulated. Vices can be envied as much as virtues. In fact, it is metaphysics that places limits on desire because it is metaphysics that attends to the question of what is real. Metaphysics stubbornly and quite rightly declares that essence precedes existence. Sadly, this is no longer widely believed; and convincing the masses of its truth now may be an almost impossible task. And yet, to my mind, it is a task worth undertaking because illusions simply cannot save us. If you are ill, for instance, you want medicine that really works, not medicine that distracts you from what works to ensure your demise.