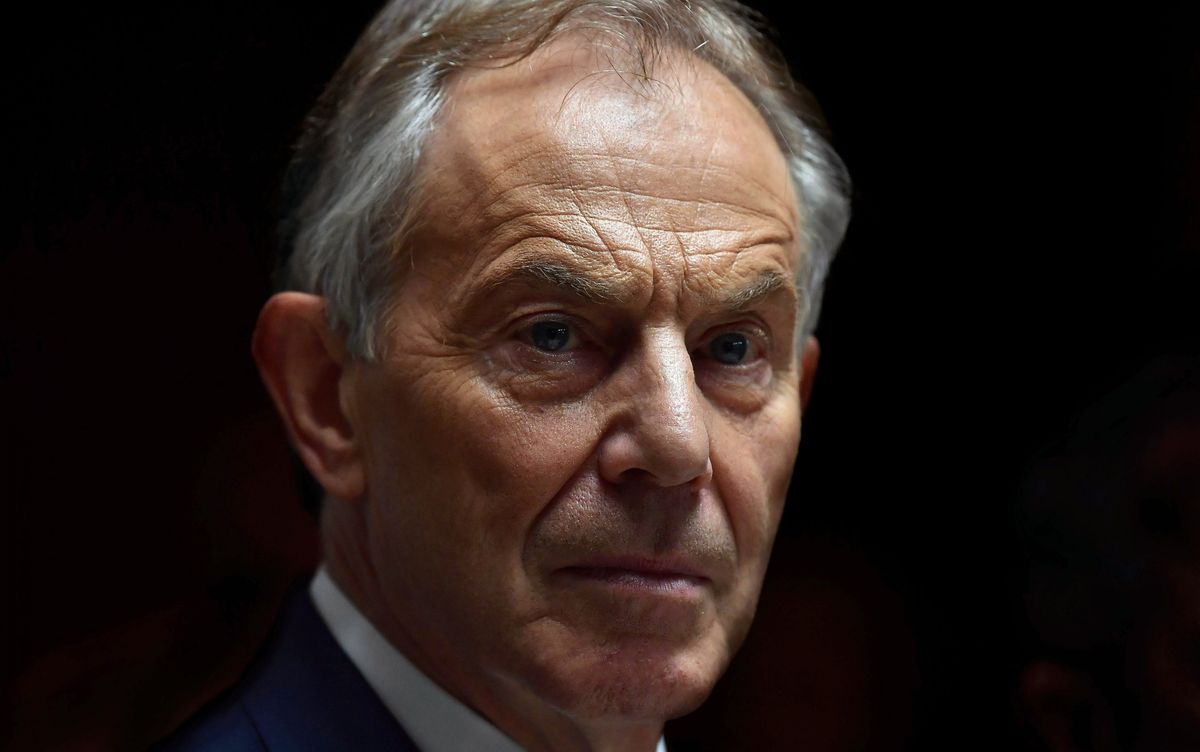

The Paradox of Tony Blair: The Schmittian Liberalism of Divine Right

Carl Schmitt 101 is rooted in an insight by Thomas Hobbes who wrote: ‘It is men and arms, not words and promises, that make the force and power of the laws.’ From this Schmitt derives many of his core principles: all power is decisionist; neutrality is a myth; the essence of politics is conflict between friend and enemy; liberalism is the delusional desire to escape politics; sovereign is he who decides the exception; sovereign is he who interprets the political formula. One of the reasons for my ongoing fascination with Tony Blair – baffling and infuriating to many of my fans and friends – is because no man in modern politics embodies the Schmittian political figure as thoroughly as him. Yet there is an interesting paradox in Blair related to fact that he views himself and is widely perceived as a liberal. We know, of course, that Blair-in-government was a basically autocratic figure who minimised the decision-making circle – dubbed at the time ‘sofa politics’ – so that he could act as a kind of New Labour Caesar working through executive action. Unlike the Tory party, he moved decisively and boldly, using and even abusing power with hair-raising ruthlessness. We are seeing just a glimpse of that now as, under his gaze, Keir Starmer is purging Labour of Far Left elements with a speed that would have made Stalin and Mao blush. Many of Blair’s basic moves as Prime Minister were anti-democratic: taking functions from the state and handing them through contracts to unelected ‘public-private partnerships’, which were actually birthed under another kind of Caesar, a Hayekian Caesar, Margaret Thatcher. But Blair went a lot further than Thatcher and did not stop there. Many ‘Blair Specials’ included: the ‘independent body’, new institutions for ‘regulatory oversight’, Quangos, and new power structures that ambiguously ran parallel to long-established ‘castles’. These were all hallmarks of Blairism. Blair-not-in-government meanwhile (in other words ‘Dark Lord’ Blair), essentially continued to do this by setting up an entire network of NGOs and lobbying for supra-national and international quasi-governmental globalist bodies that seek to influence policy and which place themselves presumptuously ‘above power’ which is to say above the legally elected governments of Western and even non-Western nations. In the popular imagination this is ‘The WEF’ but it is much bigger than that. We know all this. Much of what Blair does is profoundly undemocratic, even anti-democratic, but yet it’s still recognisably both liberal and Schmittian. Given that Schmitt was a profoundly anti-liberal thinker, how can this paradox exist in one man?

Schmitt took great pains to disaggregate liberalism from democracy. For Schmitt, liberalism is the desire to escape from and neutralise due to its utopian refusal to accept conflict as an essential feature of human affairs. Democracy, in Schmitt’s view, was quite the contrary: In Paul Gottfried’s words: ‘Schmitt saw a drive towards … a total state as inherent in democracy, which “aims at the politization of all human existence.”’ In a sense, Blair shares the second fear of democracy, although in his spin-laden language, he frames it as ‘populism’ which is a ‘threat to democracy’. But in a very profound sense, he is guilty of exactly that crime of which Schmitt charges liberalism in general: he seeks to avoid and neutralise politics.

This brings me to what I wish to highlight here: the extent to which Blair’s entire discourse and frame of reference entirely forecloses even the possibility of debate. In Blair’s world, all issues are always-already settled and always-already pre-decided, more or less pre-destined. It is a cliché to call Blair a Messianic figure, but in this crucial respect it is true: for Blair the future is already mapped out, already has a technological and progressive shape, it is foreseen, it has, in effect, already happened. The only question allowed to enter his discourse then is: how do we manage it and shape its course? The answer is always – and I mean always – to follow the plan that Blair and his team have already outlined. All deviations from Blair’s plan carry ‘risks’, all steps towards Blair’s plan represent ‘the solution’. Whether the topic is the NHS, AI, climate change, vaccines for pandemics, or Britain’s role in the international order, all possibilities and avenues lead directly to a Blair plan. But these plans all have something in common: they start from the assumption, never questioned and never allowed-to-be-question, that the changes for which Blair is preparing are happening, are destined to happen, are inevitable. The logic is always circular: we do not have a choice but to prepare for this future because this is the future that is happening. If he is ever pushed on this, he will vaguely point to China or other countries and say that the only alternative is for Britain to ‘get left behind’. There’s this great steam train – or should I say green-powered electric vehicle – coming our way at 200-miles an hour and, whether we like it or not, the only choice is to jump on it. In fact, not only that, we need to jump into the driver’s seat so we get some say on where the vehicle goes.

Despite my admiration for Blair’s political acumen on a purely Machiavellian level, I have always found this aspect of his character and method deeply troubling. We can see the ‘liberal’ part: this is a desire to escape and neutralise politics, because Blair pitches all these discussions – which are in fact deeply political – beyond politics. They become a technical and practical discussion about how to steer the vehicle; no one actually gets to ask the question: ‘hey, do we really want to be on this vehicle at all?’ Blair is irritated by ‘politics’, politics is ‘outmoded’, politics is ‘short-term’, politics cannot ‘respond to the real challenges of the future’, politics is ‘ideological’ and ‘partisan’ and ‘childish’, and most importantly politics disrupt his plans. This is very liberal. However, the paradox is that in pitching himself ‘beyond politics’, he occupies the same position as the Schmittian sovereign: he alone gets to interpret the future, he alone decides what is and is not ‘inevitable’. And this is what we might call The Divine Right of Blair. His logic is as circular and theological as the Schmittian authoritarian president, in a manner that is basically religious and which nether Thomas Hobbes nor Joseph de Maistre would have much cause to criticise if we look only at its structure as opposed to its content. In fact, the apparent insanity of Blair – and truly I do think it is insane – is in a long line of similarly insane Schmittian leaders down the annals of European history from Gregory VII to Adolf Hitler. The lethal combination of universalising and totalising married to political skill is at the heart of what Oswald Spengler called ‘Faustian Man’. And Blair is the inheritor of this, he is truly Faustian and that should be truly terrifying.

We must remember of course that all political formulas from Divine Right to ‘the will of the people’ are built on shifting sands. But I think there is something else to be learned from Blair’s Messianic vision. We should effectively adopt the language of inevitablilty and see the future we wish to see as being preordained. Until we start to think like a man Blair – the human embodiment of The Regime – we will have little chance of defeating him or it. The publisher Mystery Grove sadly had to shut down recently, but every night when its account would log off from Twitter, it would sign off ‘Goodnight, we’re going to win’. This does not have to be an empty morale-boosting statement, it can and should become a kind of manifest destiny.