The Nixon Shock: part one

The creation of the fiat dollar

It is August 1971. America is in the grip of an inflationary crisis the likes of which has not been seen since the era of The Great Depression. Owing to the declining value of the dollar, countries were scrambling to exchange their dollars for gold and gold began leaving American shores at unprecedented levels as a result. Unemployment and inflation both hover at around 6% and rising.[1] America’s situation was serious and deteriorating, immediate action needed to be taken so a confidential meeting at Camp David is arranged by President Richard Nixon. In attendance, among others, is President Nixon himself, Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns, Treasury Secretary John Connally, Treasury Undersecretary and future Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker and high-ranking Nixon aides George Schultz and Peter Peterson. Further runs on the dollar could lead to economic catastrophe, the U.S. needed to combat inflation, reduce unemployment, improve their trade deficit, stabilise the dollar and, ultimately, rescue the U.S. economy. So, on the 15th August 1971, on the strong advice of his cabinet, Nixon decided that the gold peg would be removed, abolishing the direct convertibility of the dollar into gold. And with that, the Bretton Woods system had come to an end and the fiat dollar was born. The fixed exchange rate mechanism was abolished and the U.S. was no longer responsible for having to secure overseas dollars with gold. The broader international community was not consulted about this decision. And this was the Nixon shock. By taking the action he did, it is no understatement to say that Richard Nixon effectively remade the world economy forever, which was in a pure fiat standard for the first time in history. This article explains the full implications of the Nixon shock and why it is such a significant moment in modern history, overlooked and misunderstood by so many despite the fact that the effects of it are still evident today.

The Nixon shock is highly significant because it meant that U.S. could continue spending more money than it earns simply by printing more dollars because the dollar was no longer backed by gold or any other obligations. What’s more, because of the U.S. dollar's world reserve currency position these dollars will be accepted on international markets in perpetuity.

Under the Bretton Woods agreement, the dollar was pegged to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per troy ounce and countries could convert their dollars for gold when they wanted to but after the Nixon shock the gold peg had been discarded and nations could no longer exchange dollars for gold or other assets. With that, America was free of its commitments to the international community set forth and agreed upon at the Bretton Woods conference. As a result, the dollar became a floating, fiat currency and new units of money could be printed into circulation at will. A fiat currency is a currency whose value is determined solely by the market, a currency that does not have a metallic base. Bretton Woods was finished and the fiat era had begun.[2]

A final attempt to keep the Bretton Woods system alive occurred in late 1971, a meeting in Washington D.C. led to the Smithsonian Agreement whereby the United States agreed to devalue the dollar against gold by approximately 8.5% to $38 per ounce and other countries offered to revalue their currencies relative to the dollar. Despite these efforts, another run on the dollar occurred in 1973, creating yet more inflationary problems for America. The Smithsonian Agreement lasted 15 months before it was abandoned and the gold peg was finally done away with completely.

The reason why Nixon didn’t enter into negotiations is that every time they attempted dialogue the markets would move, instability would increase, possibly leading to further runs on the dollar that the U.S. could ill afford. Author Jeffrey E. Garten says in his book Three Days at Camp David that Nixon and Connolly wanted the dollar devalued against gold more substantially; perhaps to $50 a troy ounce or even $70, but others disagreed. It was actually George Schultz who proposed removing the peg and abolishing convertibility altogether. Paul Volcker wanted to raise interest rates in order to demonstrate to its allies that Washington was serious about addressing its balance of payments deficits.[3] Nixon wanted to avoid raising interest rates because he feared it would increase unemployment and thus jeopardise his chances of re-election the following year.

The U.S. was afraid that further runs on the dollar would leave Washington exposed and at the mercy of the international community and they were not prepared to allow their gold stocks to be further depleted.[4] In Connolly’s words “Anybody can topple us - anytime they want - we have left ourselves completely exposed.” Being the ones who took the decision to close the gold window allowed the U.S. to be seen to project power on the global stage by taking the lead. Devaluing the dollar further would have the opposite effect; a sign of defeat from a weak country that lacks confidence.[5] When the British Treasury requested that $3 billion worth of dollar holdings be converted into gold that very much signalled the end of the line for Washington.[6]

There is a myriad of results, problems, and consequences that stem from Nixon’s landmark decision to close the gold window. The event has had geopolitical, economic, social, military, and cultural implications, here I have chosen to focus on the destruction of the dollar, the effects of inflation, and rising debt as well as the impact on both empire building and how it allows the U.S. to maintain its position as the global superpower. In part two I will focus on the global effects of the shock, the role of the Federal Reserve, and the broader impact it has had on the global economy.

It is important to highlight that the fiat era really started before the announcement in 1971. Nixon’s decision was merely a decree that formalised what had been taking place years, if not decades, before, namely that America had been operating under defacto fiat conditions by deficit spending for a long time prior to the announcement, this is why inflation was so severe at the time of the shock (Washington had been running deficits since the 1950s and by 1959 it had an outright current account deficit).[7] Under Kennedy and Johnson, spending was high but both presidents were reluctant to raise taxes.

A fiat currency is a currency whose value is determined by the market and by the trust and faith that all the concerned parties have in it. What is important to understand is that in a fiat system constraints are removed and money growth - by artificial means - is not held back by having a solid, metallic base but the problem is, as I will go on to show, neither is government borrowing and spending, commercial lending, and the creation of credit either. Gold and the corresponding commodity market around gold were constraining forces against excessive monetary inflation by national governments. John Maynard Keynes in his Treatise on Money (1930), said it best when he proclaimed that fiat money is “created and issued by the State, but is not convertible by law into anything other than itself, and has no fixed value in terms of an objective standard.” The relationship that money had to gold gives it value but with pure fiat money the only value money has is that which is imparted to it by the government. The problem is that, as history demonstrates, non-redeemable paper money has always been rendered worthless over time.[8]

The Nixon shock effectively meant that neither the Federal Reserve or the United States government had any obligations to the broader international community to fulfil in order to create new money: new dollar bills could be brought into circulation, essentially by decree. Though the U.S. had been deficit spending prior to 1971, they were still obligated to convert overseas dollars with gold when other nations requested and to maintain the dollar to gold equilibrium as well but the act of removing the gold peg allowed for infinite expansion of the money supply without any obligations or restraints whatsoever. This was not possible prior to the Nixon shock because Washington was, to a large extent, constrained by the obligations laid out in the Bretton Woods conference; some monetary inflation was possible but excessive monetary policy (whereby they could just print all the units of currency they wanted) was limited by the amount of gold held by the central bank (relative to the amount of dollars in circulation) and America’s obligation to guarantee that dollars could be exchanged for gold on demand. Removing the gold peg changed all that; henceforth, it allowed the U.S. government to pursue previously inconceivable, undisciplined fiscal policies of borrowing and spending, both at home and abroad, anchored by the expansionary monetary policy of the Federal Reserve, as well as allowing the United States to inflate away the existing balance of payments deficit that was the direct result of overspending in the past by previous administrations (Nixon’s included).[9] However, there are consequences to such policies, as removing the metallic base of our money has invariably led to spiralling levels of debt, rising interest rates and volatile periods of high inflation. It has debased the currency and allowed the U.S. to effectively inflate away their debts all the while allowing for continuous, unrestrained warfare as well. All the consequences I cover in this article are in some way or other a result of the expansion of the money supply and are therefore a product of both reckless monetary policies by the Federal Reserve and similarly irresponsible fiscal policies by the United States government.

The role of the Federal Reserve in all of this cannot be understated; it wields vast, unchecked power in the economy by controlling both the supply and the value of money, essentially by diktat, and, by extension, is able to set the value of goods, services, and labour in the economy as well. It is important to understand that the Nixon shock is a significant extension of the power of the Federal Reserve. A full extrapolation of the Federal Reserve is well beyond the scope of this article however I will return to the role of the Fed in part two of the Nixon shock.

Interest rates

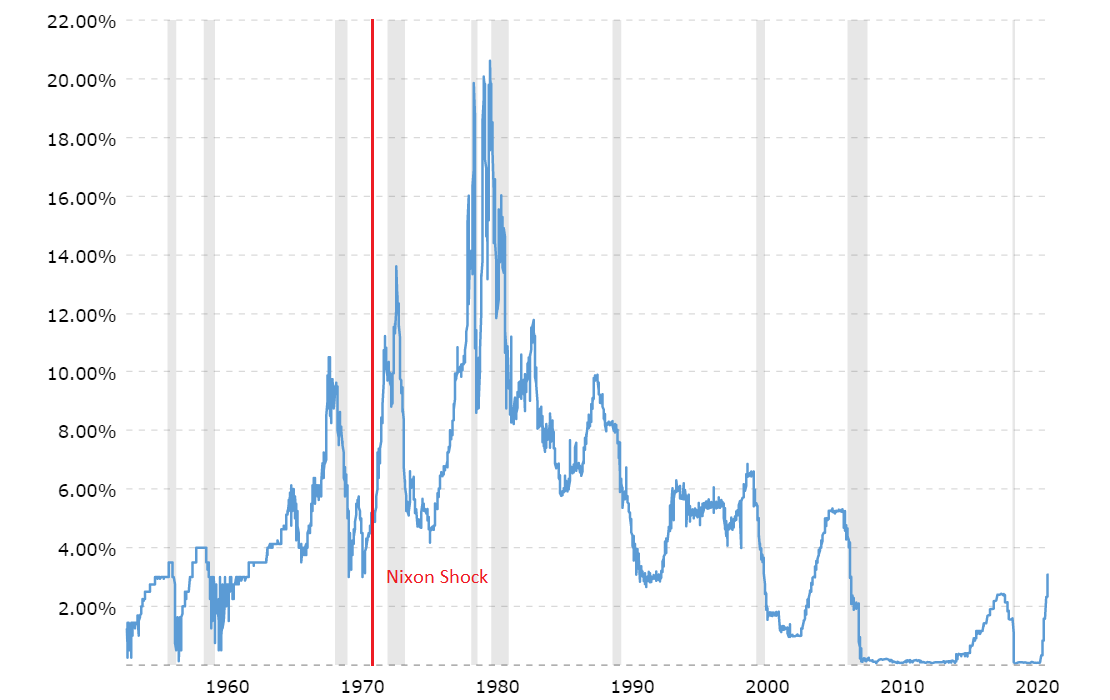

Under the gold standard interest rates remain stable but under a fiat system they normally go in one direction and that direction is up. 3.7 to 4 percent is the recommended interest rate (officially called the “federal funds rate”). From the graph below you can see interest rates grow steadily from 1960 onwards and the period of volatile rates for the United States had begun. Initially, President Lyndon Johnson didn’t want to raise interest rates because he feared it would harm his chances of re-election. Nixon also favoured lower interest rates but, eventually, rates would need to be raised at various stages, under both Johnson and Nixon, in order to be brought in line with inflation, particularly as the Vietnam War dragged on.

You don’t need to be a scholar of political economy to realise that if interest rates are too high and these high rates persist for too long then they have a severely destabilising effect domestically and this is exactly what happened in the United States during this period. During this time, business investment slowed, productivity declined, and the nation’s trade deficit grew whilst many areas of America’s economy were overtaken by the likes of West Germany and Japan. This cycle would repeat again in 1980 when soaring interest rates led to rising unemployment and recession.

For the people, high interest rates are a problem because they mean higher loan and mortgage repayments and that means less money in the economy being spent on goods and services, while for investors borrowing is made more expensive and that means less opportunity for developing industry and for investment in capital machinery and staff, invariably leading to economic stagnation.

Inflation

Interest rates mirror inflation. When inflation is high interest rates need to be higher in order to squeeze out inflation and bring it down to manageable levels. 2 percent is the target level of inflation but the U.S. crossed this threshold in 1966 and rates would not be stabilised until the mid-80s. Inflation tends to be stable under a gold standard but when the constraints of a metallic base are removed this leads to large swings in inflation that has devastating long-term effects. One of the most devastating effects of inflation is the soaring asset prices that happen as a result; especially non-fungible or non-liquid assets (that is, assets that cannot be returned, exchanged, or traded with ease or without losing value) like education, housing, and healthcare, that all have a huge impact on people’s lives (which, it should be pointed out, after having received them, in many cases people spend their entire lives paying back).

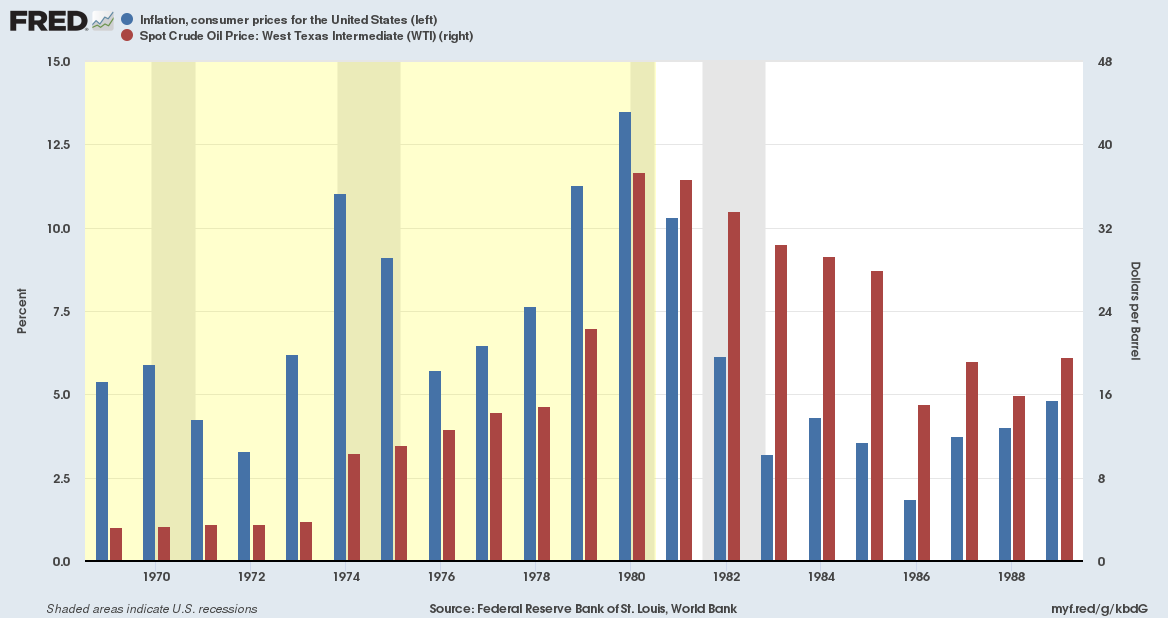

The period known as the Great Inflation lasted from 1965 till 1982 and caused a great deal of economic hardship for the United States. Prior to the onset of the Great Inflation, the U.S. was running deficits throughout the 50s. Much of the inflation was caused by war, principally the Cold War and the Vietnam War whilst Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programme also contributed enormously, as did the Space Race. Annual price rises from 1 percent in 1965 to 6 percent in 1969-70 set the scene for the double-digit inflation of the 70s.

By 1974 inflation would be over 12 percent and unemployment was above 7 percent. But by the summer of 1980, inflation was near 14.5 percent, and unemployment was over 7.5 percent. So bad were America’s problems that it gave rise to a new phenomenon known as ‘stagflation’: rising unemployment and rising inflation together, for which leading economists at the time had no solution for. Yet more hardship would follow when, in 1980, in a desperate bid to overcome America’s inflationary woes, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates to 20 percent, leading to a 16-month long recession (the worst since the Great Depression) and record high levels of unemployment (see the graph below). Known as the Volcker shock, this demonstrates that once inflation has set in restoring monetary stability is a painful and difficult exercise. The Great Inflation would not be conquered until the early 80s.

Debt

The Nixon shock ushered in the age of runaway debt. It is no coincidence that the national debt skyrockets from this moment onwards, with the dollar now backed not by a hard asset but by the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government. In the years since the gold window was closed, the lack of discipline in monetary and fiscal policy has only gotten worse and government spending has grown to astronomical levels as a result. Before 1971, there was a natural limit to how much money could be printed. New issuances were dependent on the amount of gold the country had in its possession. In 1960, federal debt was a little over half the size of the actual economy. Between the years of 1960 and 1971 the federal debt increased by 39 percent. But between 1971 and 1980 the debt increased by 128 percent (from $398 billion to $908 billion) and then from 1980 to 1990 by an incredible 256 percent (from $908 billion to $3.2 trillion). Today the national debt currently stands at $32 trillion with a debt to GDP ratio of 124%. The debt never goes away it just grows because under fiat rules the government does not have to resolve the growing deficits and the debt they produce – ever. Furthermore, Europe and Japan have followed the same trajectory as well.

Debasing the Currency

When central banks expand the money supply, they simultaneously debase the currency as well. As Murray Rothbard said, "the creation of more money makes each unit of money, each franc or each dollar, cheaper and worth less in purchasing power".[10] Historically speaking, debasing the currency has always been associated with fraud, coin clipping, for example, would reduce the amount of precious metal content in the coin (the advent of milled edges put an end to this). The modern form of currency debasement, however, comes from central banks issuing large amounts of paper money and the more units of currency in circulation the less each note is worth and the more the purchasing power of the currency is reduced. The absurdity of the current system was summed up by Forbes magazine, who said:

“So for now, we’re left with the current monetary system of unlimited money-printing, which in turn makes each U.S. dollar less valuable and each ounce of gold more valuable.”[11]

Former presidential candidate and Texas Congressman Ron Paul said:

“Since the “Nixon shock” of 1971, the dollar’s value — and the average American’s living standard — has continuously declined, while income inequality and the size, scope, and cost of government have risen.”[12]

Our currencies have been systematically debased, their purchasing power robbed and the chasm that this has left has been filled with a pernicious culture of credit and debt. We simply would not need to borrow as much as we do and rely on credit if our money retained its true value. It is important to understand that this represents not just a transfer of wealth but also a transfer of power. The steady debasement of the dollar started in 1913 with the passing of the Federal Reserve Act by the Woodrow Wilson administration but the Nixon shock is a significant extension of this. Cartelizing the nation’s banking system and moving it into private hands has steadily robbed the U.S. dollar of its true value. Inflation erodes the purchasing power of fiat currencies and eventually they become worthless. From the graph below we can see that the dollar has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1950, whilst the outbreak of war correlates strongly with a steep decline in the dollar’s value. The Joe Biden stimulus in 2020, a response to the COVID19 outbreak, added $3.5 trillion to the money supply (equal to 20% of all the dollars ever created).

What this graph demonstrates is that since the start of the Federal Reserve system the value of the U.S. dollar has been reduced by 97 percent.[13]

A common rebuttal asserts that the source of these problems were the oil embargoes of 1973 and 1979 which caused oil prices to skyrocket. However, this is largely mistaken; the fiscal policies that led to the Great Inflation predate both the embargoes: Johnson’s Great Society social programmes, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, and the Space Race all happened a long time before OPEC decided to slash oil production and place an embargo on oil exports. True, the twin oil crises did indeed exasperate the economic problems but they were not the primary cause of them, far from it. The graph below shows there is no direct correlation between inflation (the blue) and the price of oil (the red). The start of the Great Inflation was in 1965, a long time before the 1973 oil embargo.

The full network effect of the Nixon shock, and the years of monetary inflation that preceded it, meant that spiralling interest rates and inflation led to prolonged periods of volatility and instability that caused economic devastation for many, once inflationary problems set in, they are very difficult to reverse. This was all caused by the reckless fiscal policies of the government and similarly irresponsible monetary policies by the Federal Reserve, enabled by the transition into a fiat system of floating currencies anchored by nothing but “faith and confidence” in the dollar.

There was a brief moment where American hegemony was called into question and the American empire was teetering on the brink of collapse. Rising unemployment and inflation domestically, mounting pressure from the international community to devalue the dollar, the emergence of Mao’s China, the war in Vietnam, increasing competitiveness in the global economy, and the ongoing cold war with the Soviet Union all collectively all threatened to undermine U.S. supremacy. However, removing the gold standard while the dollar was still the world reserve currency would, over time, go on to be a masterstroke by Washington on the grand chessboard of geopolitics as the advent of the petrodollar system along with an expanded market for U.S. debt securities created an artificial demand for dollars around the world that allowed the U.S. to print and spend all the fiat dollars required to assemble the military infrastructure it needs to sustain and grow the American empire; funding research and development into new weapons technology, building military bases abroad, providing subsidies to the military industrial complex, and, of course, funding wars. Put simply, the American empire was (and still is) built on the back of the fiat dollar.

Even though the entire world moved onto a pure fiat standard only the U.S. was allowed to engage in excessive levels of printing, borrowing, and spending because ultimately only the United States can issue the world reserve currency freely, the U.S. dollar, whose value only the United States (by way of the Federal Reserve) can determine. This point was actually made by France’s finance minister and future president Valery Giscard d’Estaing at a meeting in Paris shortly after the announcement by Nixon: d’Estaing realised early on that the U.S. could engage in unrestrained fiscal and monetary policies as a result of the dollar’s central position in the world economy; it gave America an unassailable advantage over other countries who had to act with more restraint and discipline in monetary affairs.[14] Demand for the dollar and for U.S. treasuries and bonds is virtually permanent, this demand keeps interest rates low enough for the United States to borrow and spend all the dollars required to expand its empire as Washington deems necessary. Over time, d’Estaing would be proven correct and the overall network effect of the dollar would only increase as more and more trade would be conducted in dollars increasing its strength and liquidity, requiring countries to stockpile greater number of both U.S. dollars and U.S. debt securities, and maintaining the dollar system indefinitely as a result.

And what of the American empire now? The United States has 750 military installations in over 80 countries around the world, it plays host to the most formidable military in history, it has a nuclear arsenal consisting of 6,450 warheads and it can grant billions of dollars in subsidies to corporations such as Boeing, Raytheon, and Lockheed Martin for military contracts.[15] Lastly, the U.S. has 173,000 troops deployed around the world.[16] It is my upmost contention that without the fiat status of the dollar, the composition of the U.S. empire would be vastly different and so would the balance of geopolitical power in the world today. More gold or other precious metals do not have to be mined for new units of currency to be brought into circulation, essentially new money is created out of thin air and is then used to assemble this vast military apparatus.[17]

The relationship between war and the fiat system cannot be ignored. Franklin Roosevelt famously uttered the words “war costs money and that means taxes and bonds and bonds and taxes”.[18] Under a gold standard governments can only pay for war either by raising taxes or by selling war bonds. If you actually have to part with physical gold to pay for bombs and munitions, to pay for soldiers’ salaries, to transport all the heavy machinery then you will quickly run out of gold and the capacity to wage war is greatly reduced. Likewise, if the war is not popular among the people, then the citizenry will cease buying war bonds and the government will run out of funds. However, the fiat system enables countries to finance wars essentially just by printing money and as a result spending on warfare is no longer constrained by monetary obligations. The author David Graeber echoes this view in his book, Debt:

“Nixon floated the dollar in order to pay for the cost of a war [the Vietnam War] in which he ordered more than four million tons of explosives and incendiaries dropped on cities and villages across Indochina… the debt crisis was a direct result of the need to pay for the bombs, or, to be more precise, the vast military infrastructure needed to deliver them. This was what was causing such an enormous strain on U.S. gold reserves.”[19]

By the time it had concluded, the Vietnam War is estimated to have cost $168 billion (equivalent to $844 billion in 2019 dollars and $1.47 trillion in 2021 dollars) so Graeber may indeed have a point. Similarly, a report commission by Brown University estimates that between 2001 and 2022 the United States spent over $8 trillion on its post-9/11 military engagements.[20] This is all enabled by having a floating, fiat currency that has no solid, metallic base to it; if a gold equilibrium needed to be maintained by governments and central banks alike then the huge expansion of the monetary supply required to wage these wars and construct the vast military apparatus required to sustain the American empire would simply not be possible. This point cannot be stressed enough.

This is why many feel that the closing of the gold window by Nixon ushered in the era of unrestrained, total warfare. The Cold War went on for almost half a century, the Vietnam War for approximately 20 years, the War in Afghanistan lasted over 20 years, the 2003 Iraq War lasted 9 years as well: this just wouldn’t be possible without having transitioned to the fiat system and abandoning the gold standard. At one stage, in 2011, America was actively involved in open warfare in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, in three countries all at the same time, this is only possible because America can now finance wars by printing and borrowing trillions of dollars all in the safe knowledge that reserve currency status in a fiat system protects the U.S. dollar and the U.S. economy from the crippling effects of hyperinflation. Though some of these conflicts started before the Nixon shock, as I mentioned earlier transitioning to a fiat system absolves both past and future debt obligations.

Additionally, it should be pointed out that war practically bankrupted the major European powers in the 20th century: France and Great Britain had to borrow heavily during the two World Wars leading to the dissolution of their respective empires and a largely deferential role in world affairs thereafter. But the U.S. avoids this because of the fiat dollar and because of the dollar’s world reserve currency status too. The wars mentioned previously cost trillions of dollars, if the United States had to part with real gold or payment in specie none of these wars would have been possible. Such a privileged position was exemplified during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars when, at various stages, taxes went down (George W. Bush cut taxes in 2001 and again in 2003).

It is also worth noting that within a few short years of Nixon’s decision, the petrodollar agreement was ratified between the United States and Saudi Arabia and it would soon be extended to all the other OPEC member states. The dollar was moved off gold and on to oil (‘black gold’ as it is sometimes referred to) by 1974 and this meant that countries would now need dollars to fund all future oil purchases from this point onwards with the petrodollar system providing a convenient and timely outlet for the world's supply of excess dollars. What is also notable about the petrodollar agreement is that it led to U.S. debt securities (treasuries and bonds) effectively replacing gold as the number two asset. As F. William Engdahl says “this was a dollar exchange system, which, they reckoned, they could control unlike the old gold exchange system”.[21]

The advent of an expanded U.S. treasury and bond market is a highly significant development because it effectively allowed the U.S. to inflate away the balance of payments deficit and to disregard the other structural imbalances associated with its economy, absolving Washington from having to take responsibility for the inflationary policies of successive administrations, in effect debt financing its way out of its problems.

Conclusion

The Nixon shock is without a shadow of irrefutable doubt the single most significant event in the world economy in the post-Bretton Woods era. As a direct result of this decision the entire global economy was effectively remade forever; this is because it allowed for infinite expansion of the money supply and it also meant that all other currencies in the world were forced to become fiat as a result of Washington abandoning the gold peg. It can also be viewed as a significant extension of both American power and the central banking complex as well simply because the act of removing the gold peg meant that neither the Federal Reserve or the United States government had any obligations to fulfil in order to create new money as they were now freed from the restraints of the gold standard: new dollar bills could be brought into circulation, essentially by diktat alone. Transitioning to a fiat system enabled the U.S. to finance empire building and maintain its superpower status simply by printing money and, as a result, spending on military and war was no longer constrained by the monetary obligations outlined at the Bretton Woods conference. Now America could, quite literally, outspend its rivals in pursuit of empire and expansion: this is why the Nixon shock is such a significant event. We saw how inflationary monetary policies caused untold economic devastation domestically in the United States, having led to spiralling levels of debt, rising interest rates, volatile periods of high inflation, skyrocketing asset prices, and endless boom and bust cycles. In part two, I will look at how the fiat era ushered in the debt fuelled global economy we have today, the start of shadow banking and finance capitalism (trade in derivatives and the rise in speculation), and the financialization of every sphere and facet of life. The birth of the fiat dollar was the birth of the modern world.

Notes

[1] Dallek, R. (2007) Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power. Reprint. Harper Perennial. P.243

[2] Rothbard, M. (2021) The Case Against the Fed. 2nd edn. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p.105

[3] Garten, J. (2021) Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy. Harper. p.142

[4] Garten, J. (2021) Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy. Harper. p.182

[5] Garten, J. (2021) Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy. Harper. p.159

[6] Clark, W. (2005) Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar. New Society Publishers. p.19

[7] How the Bretton Woods System Changed the World (2022). Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/articles/forex/122215/bretton-woods-system-how-it-changed-world.asp-world.asp.

[8] Rothbard, M. (2021) The Case Against the Fed. 2nd edn. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p.29

[9] Clark, W. (2005) Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar. New Society Publishers. p.29

[10] Rothbard, M. (2021) The Case Against the Fed. 2nd edn. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p.10

[11] Holmes, F. (2021, January 25). The Gold Standard Ended 50 Years Ago. Federal Debt Has Only Exploded Since. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2021/01/25/the-gold-standard-ended-50-years-ago-federal-debt-has-only-exploded-since/?sh=5eeba54d1e17

[12] From the Nixon Shock to Biden-flation (no date). Available at: https://mises.org/power market/nixon-shock-biden-flation.

[13] Goodson, S.M. (2019) The History of Central Banking and the Enslavement of Mankind. Black House Publishing Ltd. p.74

[14] Garten, J. (2021) Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy. Harper. p.254

[15] Haddad, M. (2021c) Infographic: US military presence around the world. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/9/10/infographic-us-military-presence-around-the-world-interactive

[16] Today, C.M.U. (2023) What country has the most nuclear weapons? Can the US stop a nuclear attack? Available at: https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2022/09/03/country-with-most-nuclear-weapons/7845467001/.

[17] Clark, W. (2005) Petrodollar Warfare: Oil, Iraq and the Future of the Dollar. New Society Publishers. p.29

[18] Brands, H. (2008) Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Doubleday. p.650

[19] Graeber, D. (2012) Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York, United States: Penguin Random House.

[20] U.S. Budgetary Costs of Post-9/11 Wars Through FY2022: $8 Trillion | Figures | Costs of War (no date). Available at: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/BudgetaryCosts

[21] Engdahl, W. (2012) A Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order. New-Revised-Unabridged. Progressive Press. p.186