The Luddites and Linus Torvalds

Escaping Modernity's Bind

There is a man standing on the neck of modern thought and his name is Ned Ludd. Really, I hated Ned before I knew his name, despite him not being American, not being my contemporary, and, well, not being real. As a legend, as an archetype, the influence of Ned Ludd, the idealized English midlands weaver, was powerful. Powerful enough to inspire a group of dispossessed yeomen to smash the automatic looms they thought were going to replace them? Powerful enough to make their memory live in infamy 200 years later as the “Luddites”, a symbol of everything backwards and ignorant? Powerful enough for his movement to become the icon of everything that I thought I opposed, almost 200 years after his active memory died in infamy? Such was the power of Ned Ludd.

After all, what better villain might there be to contrast the halcyon techno-optimism of late 1990s California than the "Luddites", a mindlessly anti-technology and antiquated political movement seeking to move humanity backwards along the one dimension in which it actually seemed to be moving forward? And people may forget that in the post-“whole-earth” Golden State” of the 1990s, genuine techno-skepticism actually had some presence within the left-wing burrows of the bay area. And this negative example was more motivating for me than I would like to admit. It was with me through the course of three engineering degrees, as I learned physics, computer science, and advanced applied math. Was the technology I was working to develop making the world a better place? Was it even making my own life more rich and fulfilled? An interesting academic question, but not one I took seriously. I was moving things towards the future, and away from the dark age that all those ignorant people were trying to restore. After all, I didn't want to be a "Luddite".

Nevertheless, at some much later day, in the Year of our Lord 2022, I felt the spirit of Ned Ludd stir within me when I laid eyes on my new Nordic Track and comprehended its purpose. I guess on the outside there wasn't anything particularly wrong with this machine, a piece of premium exercise equipment that my wife had been pining over and which I had purchased for her birthday so she could "lose the COVID and baby weight". It had a hefty price tag, an extortionate payment plan, and absolutely dog-shit customer service. But once the damn thing was paid off, it did have a certain amount of impressive engineering to it. Problems didn't start until I got the next month's bill and noticed the presence of a new subscription fee. A subscription fee? For a physical machine that I already owned outright?

"It's for the app,” my wife explained, “so I can track the progress of my workouts."

But really it was worse than that. The machine was recording bio-metric information on all aspects of our physical health and sending them back to headquarters for further demographic analysis. And without this core app, requiring a regular payment, the machine that I paid dearly to own basically wouldn't work, it's functionality reduced to only a small subset of what the mechanism was capable of delivering. I at once recognized this behavior as part of a relatively new paradigm in engineering, "The Internet of Things", (“IOT”), a “liberating” new-age technology I had previously used to sell some of my own research projects. Now, being on the receiving end of IOT technology, a machine autonomously using the internet to record and modify its function didn't feel so liberating. In fact, I had never felt more a slave to my own possessions.

I couldn't reinstall new software or create a workaround. Closed form non-modular design meant all of my technical know-how involving computers and programmable controllers was for naught. And so the thing remained locked in its behavior, beyond my control to stop, serving the purpose of its true master.

At once I began seeing red. This THING that I invited into my house, purchased no less with hard earned money, had in violation of every classic norm of property and contract begun working behind my back to spy on me. Not only that, my artificial slave now had the temerity to bill me for its own treachery. I couldn't be angrier. And at once my wife had to restrain me from taking up a nearby hammer and violently falling on the machine, shouting the words of Prince Rillian from CS Lewis's The Silver Chair:

"Lie now in ruin vile engine of sorcery! Lest your masters use thee to enslave another!"

My love affair with technology was over. And its true what they say, the more torrid the romance at the start, the more likely it is to end in violence.

Really, the affair began innocently enough some Christmas in 1999 when a younger version of myself received his first computer, a large oblong plastic tower and a CRT monitor whose strange bubbly design carried none of the blocky charm of early 90s PCs, nor the sleek elegance of the computers from the late-2000s. Really, the PC itself was the lowest of low end, but nevertheless, it was love at first sight. A new world of possibility had opened up before me, and I had but to step into it.

I suppose I wasn't a complete neophyte to the world of computing. Like all young men of my time, I played video games. And I had used computers at school, even learning the fundamentals of “C” and “Chipmunk Basic”. Still, the prospect of owning my own computer was nothing short of a romantic proposition. Images from 1980s hacker-movies and John Carpenter sci-fi flicks came to mind: brilliant man hunched over green florescent displays, meticulously typing their queries into the cold silicone black box, and in turn discovering wonders and grim realities. If there was one thing Hollywood had taught me, a young mind with autonomous computing power was capable of greatness. And even if those delusions of grandeur wouldn't pan out, it would certainly be fun to try, very much an adventure.

But, the reality of being a proud owner of a personal computer was hardly an adventure in the sense I expected. It was difficult in ways it shouldn't have been, easy in ways that were oddly unwelcome. Of course, there were the standard issues with system stability infamous in the Windows-98-era of computing: the constant crashes, the “blue screen of death”, and the inability to run multiple programs simultaneously. But what I hated most was the phony user-friendliness that Windows presented; starting up programs I never asked for, attempting to solve problems in anticipation of my desires, and then, when there actually was an error, obscuring the issue at hand and preventing me from trouble-shooting the problem myself.

I expected a mystery box, a complex but discernible guide to the bold new digital frontier. Instead, I had been saddled with a retarded over-indulgent animatronic stewardess who chirpily repeated ad-lines about helpfulness while tightening a seat-belt around my throat. I wanted a real-life safari and instead got a semi-vandalized version of Disney’s “Jungle Cruise” ride, operated by a drunken controller and with half of the animals missing their heads. What was the point to it all? As the problems mounted and the solutions failed to materialize, I began to look elsewhere.

I guess this is where the figure of Linus Torvalds enters my story. I saw the name first as I perused a tech article in a computer magazine (yes, computer magazines were a thing in the 90s) describing a lone Finnish genius who had pioneered an alternative to Windows called “Linux”. This was not just a piece of software, but a new paradigm, a new way to pursue computing; not just an alternative product, but “open software” available to anyone who had the time and inclination to master it. My imagination was captured. And so, armed with an installation CD of Red Hat and a cheap Linux manual I had purchased from Borders, my journey into the world of Linux/GNU began.

Did it work? Were all my problems with user-friendliness and system-reliability solved? Absolutely not. If anything, things got worse from an “end-user” point of view. Forget not being able to run StarCraft while connected to the internet, on Linux it wasn’t even apparent how to get on the internet in the first place, and my distribution certainly couldn’t run StarCraft. Playing a CD, or burning one, required a month-long dissection of a temperamental Linux utility. And while Window’s “blue screen of death” was no longer an issue, I suffered much more serious self-inflicted system crashes simply by using the operating system continuously logged in as “root” (a rookie mistake it took an embarrassingly long time for me to learn never to do).

But somehow this was preferable, enthralling even. I knew that I had found what I was looking for the moment I was logged in and saw the Unix command line. This was now a machine that truly belonged to me. The promise of Linus Torvalds was here.

I understand that Zoomers and younger Millennials will likely dismiss my fascination with this baroque technology as a pretentious hipster affectation. And I admit, in part, there was some pretense to it. But something more vital and meaningful was going on in the open source world of the early 2000s. Everyone could feel a certain purpose in working to make software more open. No one ever talked about the philosophical dimension explicitly (except in the most vague, feel-good, hand-wavy sort of ways), but looking back on the period now, the ethical imperative of open source, felt so keenly then and gone now, cries out for a deeper examination.

What was the core of Linux’s promise? There was the standard progressive talking points. The Silicone Valley tech-gurus preaching about making access to information more equitable, an ideal that would ironically, 15-years later, turn its younger adherents against the founders of the community themselves. But looking at the phenomenon with the benefit of hindsight, I now see something different: a group of craftsman finding dignity and ownership in the work that they loved.

It sounds like a small thing, but the fact that the software was open and modifiable, changed the users’ perspective. Now that the code was amenable to manipulation and redesign (not hidden behind layers of obscurity and IP-protection), the art of using and maintaining the software became a fundamentally more human endeavor. Sure there were problems, but as described in the seminal book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, all of those problems could be conceptualized as challenges, surmountable with enough ingenuity and gumption. And in the process of solving the problem, developing a solution, the user and the developer became better at their craft. They grew in the art of the technology itself.

In a certain way, the lack of an overly-friendly exterior provided a necessary constraint, fostering a better relationship between man and machine. The classic example I return to here is the bare-bones text editor vi, a program operating with no graphical features and with only a limited range of keyboard inputs, executable on the most primitive hardware. Still, in the hands of an expert, vi could more effectively wrangle code and text documents than the most sophisticated word processors and development environments. Watching a true master at work seemed less like watching a computer-user and more like a virtuoso violinist. Was it true that there could be master users of a computer application? Apparently so. And this more challenging perspective on computing provided an organic alternative to the early digital age, so characterized otherwise by rank consumerism.

And what flowered from this more human perspective? A sense of purpose. Linux had a telos, it was a path towards a more honest method of computing, a perspective that would let ordinary people remain masters of their own digital destiny. An alternative to corporate and government domination over the individual actor. Every buggy application improved, every line of code written, was a foundation, a pathway to a better world built by the efforts of the community, and at a deeper level, ours.

There was a right way for technology to proceed, and a wrong way. Nothing was inevitable about technological development, and, as such, Linux/GNU had its heroes. The figures of men like Linus Torvalds and Richard Stallman obtained a kind of archetypal significance almost impossible to imagine in the contemporary era. Not only were their ideals represented in the code itself, their personal attitude towards technology was blazing a path to a better future, a future that we were all actively building together. Humanity had a choice ahead of us, and it seemed like we would all, eventually, make the choice for freedom and independence.

So what happened? Well, in a word, Zuckerberg. Computers and the internet changed. First slowly, then quickly. The hard edges were sandpapered off, and the internet became a space for ordinary people, less a hobby area for specialist nerds. AAA video-games experienced a second renaissance that made them worth talking about as cultural touchstones. Social media became the de-facto way of interacting socially for those under 30, and online dating promised a revolutionary way to get around the messy social interactions required to pursue romance.

The spirit of the age had moved on. Using the computer and the internet was no longer about the mastery of a tool, it wasn’t even about exploring an interesting intellectual plaything. No, the promised land of the digital commons, long prophesied, was upon us and it was time to help oneself to the delights of the virtual buffet descending in abundance like Mana from Heaven.

Looking back at the decade, it was hard to take full stock of the magnitude of the change underway. In 2003, I existed in a technology-paradigm that treasured every private piece of data as my own, fretting over the “lossy-ness” of the .mp3 format compared to .flac, deeply concerned that my e-mail might have to travel through (and be stored on) servers owned by Microsoft. By 2011, I was comfortable with my entire digital person being contained in a cell in Facebook’s meta-verse and handing over the details of my life to be broadcast and processed by a corporate entities with zero oversight and zero accountability. I suppose it came to me later as a surprise that this power was being abused?

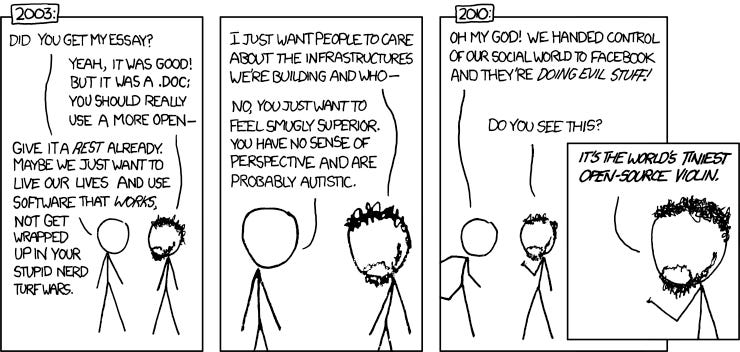

In my defense, I certainly wasn’t the only one who fell for the promises of Zuckerberg and his ilk, as lampooned by a famous web-comic.

Still, the irony was sharp, we had been suckered by the very technology we once adored. And now the engineers who thought they were the masters, found themselves slaves to a system unimaginable in the previous era, paying the machines they thought they owned for the privilege of being spied upon.

I guess this brings me back, once more, to the Luddites. Everything in my modern liberal social order had taught me to look down on these people. As a 2000s-era liberal, I was well-versed on the benefits of the industrial revolution and its consequences. I had read Steven Pinker. I had seen the graphs about the trends in living standards and life-expectancy. I knew that opposing progress, especially technological progress, was lunacy. But was that the entire story?

I didn’t comprehend the deeper dimensions of this history until I read Hillaire Belloc’s The Serville State, but the yeomen of the English midlands had lost something very real at the end of the 18th century. In the Medieval world they were a people who held themselves with pride, independent heroes to their community and nation, worthy of their own folk heroes. They had a freedom very hard for modern people to understand. But then, in the wake of the British manufacturing revolution, this world was destroyed and the people who inhabited it were harvested to become the grist of an ever-expanding international textile industry which rendered their skills and independence increasingly irrelevant. Soon, they remained little more than degraded cogs in a machine that they could not comprehend.

I suppose as comfortable modern people, we can now safely disparage the Luddites for not having the foresight to see their squalor as a necessary step towards affordable manufactured goods 50 years later? Or the development of penicillin and automobiles 100 years later? But even if we grant this strange anachronistic premise, it does seem to miss the true historical lesson that these people have to teach us.

After all, I do share in their fate now as one dominated by a machine that I worked to construct. The future of total independence, once thought to be my generation’s destiny, was bulldozed to make room for an addictive regime of social media and artificial intelligence. And if anything, I had the worse end of the comparison with the Luddites. For while the peasants of the early 19th century had their birthright torn from them forcibly through land-clearance and regulation, my cohort and I had sold ours for trinkets, flattery, and the seduction of total convenience.

I remember here an apocryphal quote by Bronze Age Pervert that tech-bro Millennials, like myself, had been “seduced by toys” into abandoning the pursuit of the sublime and the spiritual. The words hurt because they were true. Not only had I spent my entire young adult life constructing an army of digital playthings, I had then, somehow, surrendered to that army the very future that I thought I was building for myself. Early on, we had all thought that machines would handle the drudgery leaving the creative and edifying pursuit to us special snowflakes. Now, we punch cards on our tedious day-jobs while we watch AI unleash a torrent of soulless but addictive entertainment tripe, a cultural sink hole threatening to consume everything in a Landian nightmare.

I guess we probably deserve what is coming. But if I may be so bold, speaking as a man “seduced by toys”, I think there might be a way out of the technological bind, starting with the attitudes towards software that I learned traveling in the domain of Linus Torvalds.

At a basic level, I think that we misunderstand the threat (and the limitations) of AI specifically, and technology generally. People talk about “general AI”, or "the singularity", the point in the development of technology where the machine can totally replace the human, the historical moment where “the future will no longer need us”. Typically, the understanding is that the machine will replicate all functions of the human brain, to the point where the physical human is redundant, and advance technology in a direction independent of mankind’s wants and desires. But, on the likelihood of this possible future, I am skeptical.

First, the prospect of strong AI immediately encounters the hard problem of simulation, the perfect prediction or mimicry of a complex system like the human mind being virtually impossible. But also, there is the deeper philosophical question of whether the simulation of a physical phenomenon is equivalent to the actual phenomenon itself. This sounds like metaphysical nit-picking. But ask yourself, is a perfect simulation of plant photosynthesis equivalent to actual photosynthesis? Almost all intelligent people would say “no”. But then why do so many of them now think they can achieve immortality by uploading their brains onto the internet?

Moreover, on the question of machine-driven technological progress, there is reason to lower both our expectations and our fears. As in the last thousand years of human history, machines will play an integral part in driving technology, especially in the purely iterative process of carrying out experimentation and making large-scale calculations. However, most real scientific breakthroughs are not simple iterations, but are born from raw intuition that re-conceptualizes problems with different language and better questions. The idea that this macro-process of innovation can be perfectly replicated through the application of machine-based optimization algorithms within a set of formal parameters seems, to me, far-fetched, at least with anything resembling modern software run on Turing-style processors.

All of this is not to say, of course, that there is no “AI-risk” or "technological threat" to the human race. There absolutely is. As it stands, modern technology is the greatest threat our species has faced for the last 4000 years. But the true "AI risk" is very different from the nightmares spawned from The Terminator and The Matrix. It is less about the power of machine learning algorithms and CPU speeds, and more about human morality, personal discipline, and how we as a species value the relative worth of each other.

It is true that technology is de-humanizing the world; it has been since the advent of the industrial revolution. But our humanity isn’t seized from us forcibly. We sell our agency to the modern world for scraps of numbness and pleasure. Machines obtain their power over humans by flattering our indolence and convincing us that we don’t need to ask for more than what they can provide. This is a process I call “hyper-modernization”, where people are trained to define their existences through increasingly debased consumer-desires just as the machines are trained to more efficiently fulfill them. And in this process, we humans lose our sense of purpose and replace it with radically de-territorialized forms of indulgence, devoid of meaning.

For this reason, the “Turing Test” is rightfully seen as the ultimate test of AI power because it tests human-machine relations at the point of CONTACT. Do you think this thing talking to you is a real person? Are you asking the right questions? Do you care enough about the "humanity" of the interaction TO ask the right questions? Here artificial intelligence's role is less to outsmart us than to soothe us into oblivion. It's not the chess master finding a new winning move with unbelievable forethought, but a cooing nursemaid trying to silence the patient’s objection to the procedure underway. All in all, the internal quality of the process matters substantially less than our acceptance of its authenticity.

To vary our analogies, it might be instructive to compare the power of AI to that of fiat currencies. They have the value that we, collectively, choose to give them. But this does not make their power any less real. Moreover, like fiat currencies, the ultimate macro-cosmic effect of the technology is to export our personal agency to larger managerial systems and actors beyond our control. Worse, since the managerial classes of the West benefit from the process of centralization, they have every incentive to encourage laziness and unhealthy habits within their subject populations, knowing that the technological solutions introduced will justify their ruler-ship, even as their ability to rule wisely radically diminishes.

And what is the ultimate end of this process? Many have speculated, but my favorite is found in C.S. Lewis’s masterpiece The Abolition of Man. In Lewis's view, the conquest of nature will continue until the point where technology conquerors human nature itself, and the feedback-loop closes. Therefore, all subsequent generations will become the playthings (or slaves) of whatever intelligence exists in the unique historical moment when the creation of new sentient creatures becomes totally manipulable, an apocalyptic technological singularity controlled by an intelligence that possesses no connection to humanity or the function of ordinary morality.

But really, the dystopian description of these bad end-points distracts us from the issue at hand, namely that all of this is a matter of choice. The process only seems inevitable in the abstract, but it only has the power that we choose to give it. We just have to reassert our ownership and independence.

However, the confining paradox of our age is that the very tools that we need to escape the confines of modernity are also the shackles that bind us to its contradictions. The open media platforms people use to expose and discuss alternatives to the modern order are also addictive substances that implicitly enslave us to our more base natures. And, as many others have pointed out, we need to radically alter our relationships to these technologies if we want humanity as we know it to persist.

In a sense, the darker elements of artificial intelligence, the "internet of things", and social media abuse are clarifying about the true relationship we have with machines that started in the industrial revolution. As the stronger forces of the digital revolution reach into our lives and seize control, our chimp-power-grabbing brains react, and mankind gets a wake-up call on a century-long negative trend.

We need to start with the fact that humans cannot own modern technology (computers, iPhones, social media accounts) in the same way we own pre-modern technology (hammers clothes, violins, and saber). This being the case, our fundamental instincts about the possession of objects, so useful since our advent as hunter-and-gatherers, is deceptive to the real power relationships going on.

Once the design of a piece of technology becomes opaque, it becomes essentially magical to the ordinary user. You own a hammer, you use a hammer to "hammer", anyone can see the purpose of the hammer and describe their relationship to the hammer complete from beginning to end. The same is obviously not true for an iPhone.

Of course, the mystery is not absolute, there are always certain "specialists" who can see through the trick. With great effort and training, one can become a master, and therefore an owner, of a certain complex technology. But ordinarily, the workings of these things is not apparent to our lizard brains. And for the common man, the ultimate purpose of a complex machine is beyond their understanding.

Ironically, as we attempt to demystify the cult of techno-optimism, it may be useful to employ a spiritual perspective, re-imagining the modern automatons which rule our lives in the way our pre-modern ancestors might, as “the demon engine” or “the ghost in the machine”. After all, our ancestors were not wrong to think of things like books and rings as the potential home for demonic spirits, ready to corrupt the human soul. They were cautious of objects that exhibited “power”. Should we be any less, now that our own possessions exhibit observable agency in contravention to our best interests?

The main take-away from this approach can be simply stated. Whenever we use a piece of modern technology, there is an implicit dialectic, a political battle of wills, between ourselves as humans and the dark design behind the machine itself. When man interacts with technology, there remains an implicit question. Is it I who use you? Or is it you who use me? What end will our interaction ultimately serve? And who is the ultimate arbiter of our relationship’s purpose? These are questions we are not used to asking our inanimate possessions, but already the lack of awareness has cost the human race dearly.

Can centering existential questions about the technology’s purpose create a healthier relationship between human and machine and preserve the authenticity of life? I think there is reason to be optimistic.

What is needed now is less a “Butlerian Jihad” (a great technological reset so to speak) than a “Butlerian Code:”, regulations or guidelines that can center a healthy relationship with machines and limit their ability to assert external control over our lives. We need guide-rails towards a more human future, at the legal level, the design-level, the user-level, and the spiritual-level; a technological “Reconquista”.

This sounds hopelessly naive, but I wonder why intelligent people dismiss what is the obvious way out of modernity’s bind. Human agency can (and will) dominate the direction of technology. If history itself isn’t enough evidence to demonstrate the thesis, the emergence of ideologically catechized AI should close the issue. If we can write adaptive chat software to assert progressive political platitudes across a myriad of unrelated questions, why can’t we write software that maintains humanity’s physical and spiritual health? And here the lessons’ from the open-source communities of the early 2000s can be instructive.

In the mode of Linux/GNU, the process of “technological reconquista” begins by reclaiming ownership of our technology at the most basic level, breaking its link to the corporate managerial motive driving it to evolve into ever more addictive skinner-boxes. It continues by redirecting design towards the ultimate benefit of the end-user. Perhaps social media platforms designed to limit peoples’ para-social and narcissistic tendencies? Perhaps devices that focus people on a core purpose rather than diverting them into click-holes? Already, we see the beginnings of this with SubStack and Urbit, but the trend needs to go much further.

More broadly, a “technological reconquista” would have to challenge our core understanding of ownership over complex machines and digital objects, starting with a different set of questions. What would it mean to be a good steward to an online space? And how would this online, in turn, support real-life community? What would it mean to be a good user of a computer application? What would it mean to be an craftsman of a digital art? After all, if all healthy human interactions with tools is in the mode of the “artisan”, can we recreate the quiet dignity of vi? How do we teach users to becomes yeoman of the digital world? And would the introduction of certain digital technologies broadly enhance a social ecosystem of non-experts?

And of course, in response to any of these questions, we should be able to say “No”. In fact, “No”, should be our default response to any technological novelty lobbying for broad integration into human society. Let the machine prove its utility to the human purpose; there isn’t any hurry.

I suppose the ultimate end of this paradigm shift involves a spiritual examination of the relationship we have with machines. Humanity needs to train itself to have an adversarial attitude towards its possessions in general, technology in particular. We need to be ready to wage spiritual warfare against the implements of the modern world, even as we use them for our own survival. What will this mean? I don’t think anyone has the answers currently. Perhaps the change will be so radical, it will correspond to a kind of cultural revolution, after which, the use of technology will be gated behind religious ceremony. A litany spoken before we touch a silicon device? Examinations of conscience to keep our minds in the real world? Repentance and contrition for accidental techno-idolatry?

This all sounds fanciful, of course. It’s early days and nobody knows what a post-modern world would look like not barreling towards apocalypse on “auto-pilot”. But I am certainly not the only one thinking in this direction.

Still, while a lot of people are speculating about this kind of solution, few are seriously talking about it. I think this lack of serious dialogue is due to a certain thought-terminating objection, lurking forever in the back of our minds, keeping us thinking in the mode of the status quo.

The objection sounds something like this:

Sure, we all understand that technology has a radically dehumanizing component to it. We all have a growing realization, that the modern world has done very little recently to improve true human well-being. But all of these solutions about ownership, about craftsmanship, and about directing technology “symbiotically”, are simply forms of cope. We can’t actually direct the flow and development of technology itself, because by directing technology, we would be limiting technology, cutting off avenues of power that could and would be used against us by our adversaries. Even if we did try to stop the pathological progression of modernity, we would just be destroyed by rivals who didn’t. And so even if we avoid the doom prophesied in The Abolition of Man, we will simply meet a different doom brought to us by Charles Darwin.

This is an excellent objection, one that I take very seriously. However, I think this perspective is wrong-headed because it assumes the very progressive fallacy we should all now be questioning, namely, that further developments in technology correspond, necessarily, to adaptive advantages for survival.

After all, modern technology is corrosive to the survival of the organic brain, why would it not be corrosive to the survival of the inorganic brain? Why would AI, even very intelligent AI, not get sucked into an autistic rabbit hole pursuing ends that were immaterial and inconsequential to the fate of the material universe? Why wouldn’t it just waste its own time following meaningless objectives, in entirely simulated realities, just like so many other very intelligent humans?

For all the nightmare scenarios about world-ending AI, from the images of soulless legions of killing machines in Terminator to the dark prophecy of Roko's Basilisk, few, in my mind, remain more plausible than the “Dead Internet Theory” in which computers, having dominated the “supply side” of almost all financial transactions are set to the problem of fixing the “demand side” of the equation and are trained to become more perfect consumers.

What hypothetically proceeds is a farcical future where both sides of almost every transaction are “fake” with little corresponding real-world impact. As both parts of the equation are “optimized”, the desires of the artificial consumer become more base and “sustainable”, the procurement more efficient, and the transactions become a buzz of increasing frequency and declining amplitude, burning itself out in total irrelevance in the limit.

When it comes down to it, the prospect of AI organically developing a kind of Nietchean “Will to Power” is remote, like sniping a flea off a dogs back by randomly firing a high-powered rifle from across the Atlantic ocean. Rather, the almost-certain end point of modern technological developments is for both the user and the mechanism to gradually transform into automatic high-speed masturbation engines, constantly sucked into ever more trivial pursuits of ever more misguided objectives.

Ironically and in all likelihood, the horrific maw of the AI basilisk will open only to wrap itself around its own back end, the dragon of modernity gelding itself to become a technological ouroboros, an evolutionary dead-end.

An in this process, real humans, living organically with more directed(limited) technology stand a damn good chance of owning the future. After all, they are the only ones accustomed to owning things, taking responsibility, and fighting for things that matter. After everything is said and done the men and women who step off the runaway train of modernity will have an advantage over other technology-dependent humans and also the autonomous machines themselves.

Put starkly, and in a more “Carylylian” way, it takes an aristocratic temperament to rule the world. And men trained by robots, to think like robots will never be anything more than robots. Which, true to the etymology of “robot”, is just a longer way of saying men trained to be slaves will always remain slaves. For what else is a slave than a being that cannot take ownership over its own future? And isn’t that the true threat of modernity? That the human race will submit to enslavement by forces that aren’t even conscious?

I don’t think that this is our fate. The slave and the cog will naturally be subservient to the spirit of the aristocrat, even the aristocratic peasant. People, even poor people, with ideals and dreams will inevitably dominate over the ornate and complex things of a debased nature, whether they are steel, silicone, or flesh.

And so in the final tally, as ironic as it may sound, Ned Ludd will have his final victory over the machine.

Us weavers always do.