That Old Confidence

He never looked back. Not once.

Last year, just before Christmas, I was reading a book on the Cold War, and I remember being impressed by the ability and confidence of America’s leaders—men who safely navigated the nation through one of the most dangerous periods in its history. Decades later the United States finds itself on the cusp of yet another treacherous period, but this time our leaders appear woefully inadequate, with that old postwar confidence replaced by a toxic hubris.

The situation here at home may be even more dire. While the counterculture of the 1960s helped to break a president and accelerate social divisions, the old political consensus that carried the nation through World War II remained mostly intact, continuing on until the end of the Cold War.

More than thirty years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union, but rather than waxing in confidence, we find ourselves brittle, unsure, and plagued by anxiety. The old consensus has disintegrated. And while this is celebrated by the radicalized fringe of both the left and right, there are unintended consequences on the horizon we can hardly fathom.

I said as much in a post from December of last year:

Many of us are troubled to see the rapid disintegration of the old consensus that carried the nation through WWII, the Cold War, and all the turbulence in between.

Surely it was a rare moment for America and the world—one we’ll never see again—but we’re still left with a crumbling dam holding back a terrible flood; if you can’t see it now, you never will. That consensus was holding together countless compromises, arrangements, and understandings as well as bearing the weight of more than 400 years of history.

Again, it was inevitable that the old consensus would break down, but unlike other periods, certain questions—the oldest and most fundamental—are again up for grabs. What America is and ought to be, what it means to be an American, are now open questions, and until they are resolved, no new consensus will emerge.

This is where we are.

My dialogue with Darryl Cooper, “American Ethnogenesis,” as well as our recent debate with Scott Greer and Ben Roberts (more on that later), touch on this problem.

For the United States to endure as a nation, a new national consensus must emerge. And just in case you misinterpret my sense of foreboding as a desire to return to the old consensus, let me say once and for all that I believe any attempt to restore the old postwar consensus is doomed to fail. Too much has changed—we have changed.

Now for those who might be confused, what I refer to as the “postwar consensus” is the near-unanimous support for the political and economic order that emerged during and after World War II that enabled the United States to retain its national character while embracing empire and global hegemony. This transformation gave rise to, among other things, a new monetary order, the military industrial complex, international intelligence, the modern administrative and welfare state, the “imperial” presidency, a revolution in civil rights, and the redefinition of citizenship.

For these complex systems to remain strong and effective, they had to have legitimacy and renovated moral underpinnings. This was no easy task, and there was resistance, but the new order ultimately succeeded and its power and authority was largely unchallenged for more than fifty years.

I spend a lot of time on this period, and I am always amazed at how familiar yet alien it seems. Just as it’s difficult to imagine able and confident statesmen crafting US foreign policy, it’s difficult to comprehend our country leading the world in K-12 public education, payrolls increasing by 32% during the course of a decade, or just three television channels delivering the “news” to 200 million Americans.

I sometimes have the same reaction to my own family, where my grandparents seem more distant in some ways than their parents.

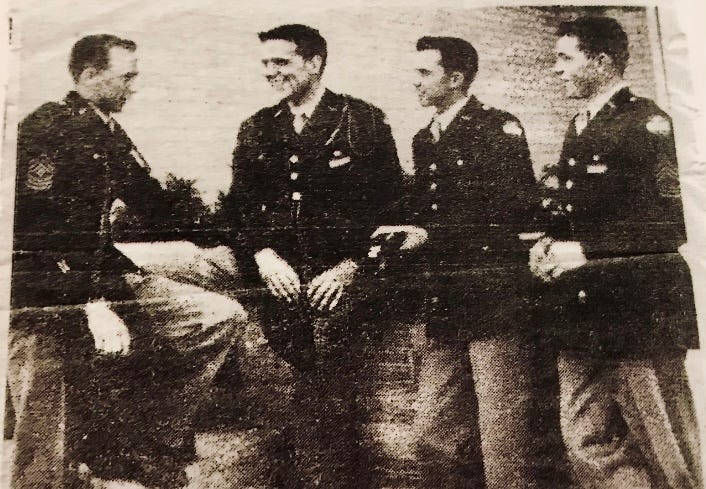

Several days ago I was up late again, doing some light reading, and my mind drifted to my granddad—one of the most confident and able men I’ve ever known. He seems to visit my thoughts more frequently now, and I find myself wishing I could talk to him…

Granddad was the first of his family to escape farming—most likely the first in centuries. He left it all behind when the getting was good, with all that postwar confidence swelling in his chest.

He never looked back. Not once.

I wonder how often he thought of his own grandfather as he was taking a slice. More than once, I suppose, as they were both orphans.

But did he look to that man for some ghostly wisdom like I do now?

His own grandfather could have hardly dreamed of such a place and time, for he came to this country penniless and weather-beaten, a pistol in his belt and a bit of scribbled paper swallowed by his hat—the last traces of a father abandoned on the banks of the Mississippi River.

That first orphan never knew Eden, just sweat, blood, and tears in a wild place. Hot suns, cold moons, and a pillar of fire off in the distance. He shot a man in the guts and was nearly lynched for his trouble. But even in wild places the Lord can show a little mercy.

I can hardly imagine a country so buoyant and self-assured: neat rows of little houses with tidy lawns, a spacious family car, and a pile of kids—bowling for him on Tuesday, bridge for her on Thursday—a vacation in Hawaii, Dion on the radio, a man on the moon…

The country was younger then, but it had already outgrown itself; a lot of anger, fear, and sickness in those days. He found it in every place, but he just pressed on—through the Indians, baldknobbers, and rustlers, until he found his own dusty spot. And there he built himself a life.

I’m not yet an orphan and I’ve never been brought to the hanging tree, but the neat rows of little houses with tidy lawns I remember are now gone, and all the neighborhood kids have melted away. Tuesdays and Thursdays are for fretting, and Hawaii sags on the wall.

There’s no confidence in this country—just anger, fear, and that awful sickness. So far from Eden it’s now a wild place—just like the first of us found it—redeemed only by sweat, blood, and tears, as the ghostly wisdom goes.

But once in a while I hear his whisper: even in wild places the Lord can show a little mercy.

Maybe this is a time of second chances, a time to build something new in a wild place. Or perhaps there we will find some of that old confidence.

Ruins of Corotoman is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Subscribe