State elections in Bavaria and Hessen show the establishment parties to be in decline as political momentum shifts decisively to the right

Yesterday was election day in Bavaria and Hessen. Just over 23% of the entire German population had the chance to express their political preferences at the ballot box. The results were not only a slap in the face to the parties of the federal coalition, but also yet another sign that our centre-right establishment, consisting of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and their Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), have entered a period of long-term decline. In her long and calculating chancellorship, Angela Merkel traded the long-term viability of the CDU for personal power and success, and the political landscape of the Federal Republic will never be the same.

First, the details:

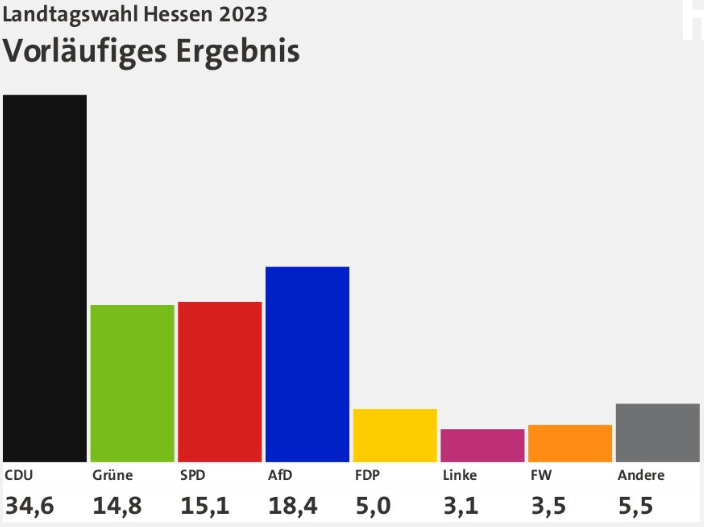

In Hessen, the Greens drew only 14.8% of the vote, the Social Democrats (SPD) 15.1%, and the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) 5% – down 5%, 4.7% and 2.5% respectively from the last elections in 2018. The coalition government is the worst Germany has had since the war, and voters miss no chance to punish them.

The CDU on the other hand won 34.6%, improving on their 2018 performance by 7.6 percentage points. The press have declared this a triumph, but the historical view paints a much more dismal picture. The 2018 elections were an unprecedented rout for the CDU in Hessen, in large part because of the political turbulence caused by Merkel’s migration policies. Yesterday, in a kind of return to baseline, they saw what was merely their second-worst showing since 1970.

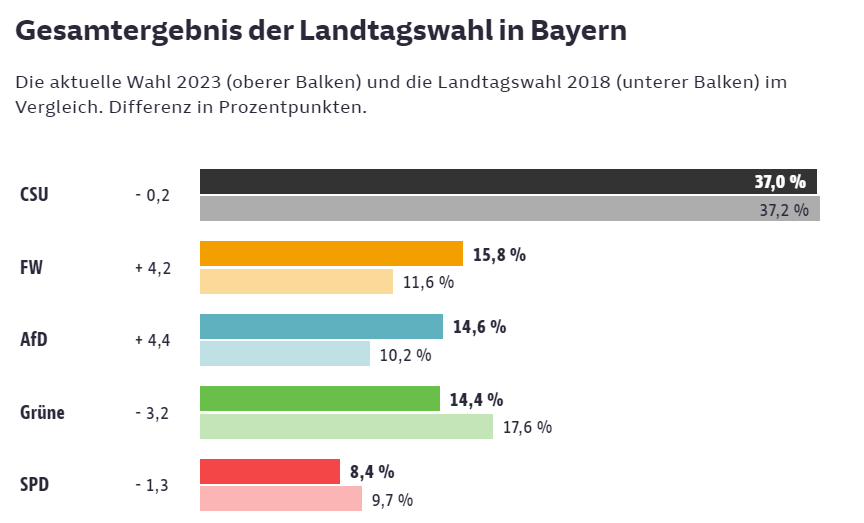

In Bavaria, where the CSU used to rule with an outright majority, things are even worse. Here, too, the federal coalition parties faced round rejection, with the SPD claiming only 8.4% of the vote (vs. 9.7% in 2018) and the Greens 14.4% (vs. 17.6%). The FDP, meanwhile, achieved only 3%, and will thus be shut out of the state parliament entirely.

The real story is however the CSU, which won only 37% of the vote – 0.2% less than the electoral disaster voters dealt them in 2018, and their worst result since 1950:

The problem is clear: All the support from voters alienated by the policies of the coalition government that should be going to the CDU and CSU, has been bled instead to parties to their right. The AfD at 18.4% are now the second-strongest party in Hessen, and at 14.6% the third strongest in Bavaria. They would have even more support here in my home state, if they did not have to contend with Hubert Aiwanger’s Freie Wähler, or the Free Voters, a “liberal conservative” party that benefited from a transparent smear campaign conducted at the last minute by the Süddeutsche Zeitung. The purpose of this campaign was to discredit Aiwanger via nebulous allegations of schoolboy antisemitism and force Söder to form a governing coalition with the Greens instead. Naturally, the effort backfired, and the Freie Wähler surged in the polls, winning two direct mandates and leading in four districts. With 15.8% of the vote they are now the second-strongest party in the Free State.

Demographic details banish all doubt as to the downward spiral of the CDU/CSU. Loyal Bavarian boomers still voted for the CSU to the tune of 47%, but they do vastly worse with every younger cohort. Only 23% of those between 18 and 29 years of age cast their ballot for the CSU yesterday. In Hessen, where the AfD is the second-strongest party for every age group under 60, the picture is basically identical. The AfD is strongest with Bavarians aged 30 to 59 and with those in the trades, while the Greens remain primarily a party of educated midwit urbanites in Munich.

A year before his death in 1987, then-Bavarian Minister President Franz Josef Strauß famously said that the CDU and the CSU could not survive the emergence of political parties to the right of them. Their long-term viability, he argued, depended on remaining the “political home” for the entire spectrum of “democratic conservative” voters in Germany:

The CDU should not give in to the belief that, in order to tap into new constituencies, they can forget their core voters, or that there’s no need to account for national conservatives or national liberals, or that those resettled after the war don’t matter, or that the rural or farmer vote is not important.

This would be a miscalculation, and I have said – incidentally in full agreement with Helmut Kohl, who also shares this view and has discussed it with me a hundred times – that there must be no democratically legitimate party to the right of the CDU/CSU.

Of course, I’m not thinking here of right-wing radical fools, we want nothing to do with them, but rather of the normal democratic conservative voters, who must find their political home with us. If the CDU adopted a new policy that repelled these voters, just 5% would be enough to throw the whole scheme overboard. For then the CDU, CSU and FDP together would no longer have enough [for a governing coalition].

Ironically, of all people, it was Helmut Kohl’s protegée Angela Merkel who destroyed Strauß’s delicate strategy during her 16-year chancellorship. From her increases in funding to left-liberal state media, to her constant flirtations with Green policies like the nuclear phase-out, to the self-imposed migrant crisis of 2015, she moved the CDU steadily to the left. In doing so, she triangulated to secure short-term electoral advantage, at the very end of a long era in which the political winds always blew to the left. She courted precisely those “new constituencies” against which Strauß warned, leaving ever greater swathes of the German electorate out in the cold. Now the winds are blowing to the right instead, and what Strauß feared has come to pass. The AfD has established itself firmly to the right of the CDU and the CSU, and they will never recover.

In consequence, Germany finds itself oddly out of balance these days. We are governed by establishment politicians and preached at by media pundits who came of age in the long Merkel era, and who have yet to internalise the magnitude of the shift that is taking place directly beneath their feet. Part of this imbalance probably emerges from the pandemic, which amounted to a nearly three-year distraction from ordinary politics, and which accelerated many trends that had long been in the post. Another part is probably down to the general decline in political elites that we see everywhere in the West. The question now is whether they will have the wits to reorient themselves, moderate their policies and seek some minimum of credibility. Alternatively, they can return to the authoritarian approaches they first tasted in the Corona era, ban the AfD, and repress the alienated electorate instead. Because they are irretrievably stupid, I expect them to make the absolute worst choice.

In other news: I recently appeared on the excellent James Howard Kunstler’s podcast. We talked mostly about the unending insanity that is German politics. Perhaps you’d like to listen.