On Folk Culture and the "Extended Universe"

A letter concerning the development of dissident art, and included prototype

In 2021, the platitude "Get Woke, go broke" is dead. Everyone got woke, and no one who got woke went broke. The meme was on life support before 2019. In 2021 its corpse is starting to smell. Did anyone ever believe this? Probably not. And from this point onward we should be honest about our situation, there would be more dignity. In present year there isn't a single Intellectual Property (IP) that isn’t slowly conforming its theme to the sensibilities of Gay-Pride and Black Lives Matter. What's next? Intersectional Shakespeare? Female Space Marines in Warhammer 40k? An even more woke version of Star Wars? Maybe this next time they could take a stand and make the protagonist a transgender demi-queer Wookie? Would that be enough to break ground? The pattern is always the same. While broad, the arc of our moral universe always bends towards Steven Universe. From space opera to race opera.

It is true that in Current Year we can't have nice things. Nice things are just too dangerous for our increasingly paranoid ruling class. Culture, even pop culture, is a weapon in the hands of its enemies. To paraphrase the original Big Joe: if ideas are more powerful than guns, and imagination is more powerful than ideas, why would a government that regulates guns allow their citizens to have unregulated imaginations? The logic is pretty air-tight. And looking forward into 2022, we really shouldn't expect anything different. What? Are the progressives going to suddenly stop believing that they are on the right side of history? Are they suddenly going to get peevish about using state power? Don't everyone hold their breath at once.

Indeed, dear reader, it is getting stuffy in here. It’s not just you, it’s not just me, and it’s not just all of us being locked down for more than a year. The claustrophobia is creeping into our lives at a much deeper level. It begins behind our own eyes. There is a narrowing of our horizons, a throttling of the number of futures we are even capable of thinking possible, a closing of the western imagination.

More and more, these days, I have come to believe that the most lamentable thing about living in a declining civilization is the utter lack of imagination. I am not just talking about politics. The slow ruin of cultural innovation is real and has been working its slow poison on our society for decades, moving, as always, from the top of things down to the very bottom. It was first noticeable decades ago when the trickle of good modern art and music virtually ceased. Now, 30 years later, it's not only impossible to find a watchable Oscar-nominated movie, it’s nearly impossible to find any reliable avenue to just "turn your brain off" and enjoy some stupid science-fiction that isn't infested by banal political tripe and the unmistakable whiff of elite self-flattery. Forget wanting to "win the culture war", most people just want some respite. Is there no end to this ride? Is there no returning to the way things used to be? What was said once long ago bears repeating: we can't keep living like this.

A question I hear commonly from watchers of my vlog is how we can find good things inside our fundamentally corrupt society. When people say this they don’t necessarily mean beautiful or spiritual things, just good things, wholesome things, lasting things, or maybe just fun things. We always have to be careful of nostalgia, but it seems most people can’t help but remember better times every time they look at the absolute state of culture in 2021. I remember in 2014 using the phrase “You couldn’t make something like that these days” in reference to un-PC films like Blazing Saddles and un-PC books like “Fight Club”. In 2021, the phrase “You couldn’t make something like that these days” applies to almost every piece of notable culture from the last two centuries. So can we have nice things anymore? No one seems to be making them.

People speculate that, in the future, we will only have the nice things we can create. But to date, most attempts to break free from our present culture, and go in an autonomous direction, fall flat on their faces. And even when these projects don’t fail, they tend to under-deliver. At this stage, I can tell that people are asking themselves whether independent cultural creation is even possible. How could an autonomous and healthy cultural space make a comeback in late modernity? This question needs a much better answer than those I have heard to date.

My last letter on Substack was criticized for focusing solely on critique, trailing off into airy-fairy platitudes about some “larger” goal, never specified. In this letter, I intend to break with this pattern and deliver a message that is 100% solution oriented. Beginning with the problem of creating independent dissident media in broad allegorical strokes, I will end the letter with a myopically focused crack pot-solution, which if followed could offer a "proof-of-concept” way to effectively organize a collective art-project for interested non-progressives. In all likelihood this letter is going to be a mess, so it’s probably fair to provide some sign-posting for people who want to skip-around.

The letter (as published on Substack) will consist of 5 parts. Part 1 describes the problems of common culture in modernity in broad strokes, part 2 outlines a dissident solution and its attendant problems, part 3 explores the nature of folk culture and how such a concept could patch problems with collective undertakings, and part 4 outlines a specific solution approach with part 5 providing an outline of a hypothetical implementation, well within the reach of someone with a moderate amount of resources.

Once more, be advised. I expect a certain divergence of tone in each section. Read what you need. Stop when you want. Hopefully you’ll find at least one part of this letter interesting and useful for your projects.

Part 1: The Ruin of Our Cultural Ecosystem

The right has a creativity problem. At this stage even mentioning this cliché is so tired that I feel dirty writing it. But, cliché or not, this is our starting point, so we have to repeat the familiar line of questions that everyone has already asked themselves. If our culture is woke, and woke culture sucks, then why don't the non-woke just build their own new culture? How hard could it be? All of these popular corporate Intellectual Properties (IP) started somewhere didn’t they? To date, while the construction of a new non-progressive culture has been the hope of right-wingers since the 1980s, nothing like a right-wing cultural renaissance has come to pass. Why is this?

There are many explanations which vary depending on the side of the political spectrum you ask. If you ask a leftie, the absence of non-progressive culture is due to an inherent lack of creativity endemic to the diseased nature of the right-wing mind. If you ask a rightie, the problem comes down to a lack of institutional support. For my own money, however, these cute explanations miss the point. The problem is much larger. We are dealing with an issue of a decline in our culture at a deep level. It is less a problem of who we are, and more a problem of where we are as a civilization. It is less an issue of right-wing vs. left-wing, more a problem of the social environment in the early 21st century.

The real problem (a la Mark Fischer) is not right-wing non-creativity but rather a lack of creativity in the West writ-large. People are faster to notice this on the right because the right is the weaker party, the party with less institutional support. But the issue of cultural decline is society-wide. In some sense, the left is less immune from the decline than it is oblivious to it. They see their side winning, with more corporate media outlets repeating their slogans. But is this growth due to the emergence of a radical new progressive imagination (as people dreamed of in the 1960s)? Or is it just institutional creep?

In 2021, any progressive might be forgiven for asking where all the new leftist visionaries are hiding. If this revolutionary age of progressive ascendancy is really a new 1968-style cultural revolution, where can we find the great poets of our time? Who are the Beatles of 2021? The Bob Dylans? Heck, I would even accept a modern day Barbara Streisand in a pinch. But wish as any leftie might, there are no great 21st century progressive luminaries, no great 21st-century progressive artists, no memorable 21st century progressive authors. In the grim bleakness of early 21st-century progressivism, there is only conquest, never creativity. And I imagine this must be a little disconcerting for any earnest progressive, at least if he thinks about it. Opening the paper, scrolling through Netflix, or even watching the academy awards, can a progressive easily come across a piece of culture that isn’t repeating his own social values back to him in the most banal lowest-common-denominator way? This mainstream ideological sycophancy might be fun at first, but to any thoughtful person, it might lose its charm quickly and become inauthentic if not outright creepy. All of the culture is left, but is there any real culture left?

In the age of social media and woke-capital, creativity seems to have evaporated or fallen into strange and predictable cycle of outrage, narcissism, and reaction. The issue isn't decline in demand for good art, it might not even be a decline of raw talent in artists (although I suspect, at some level, this may be the case). The problem lies in something deeper and harder to point out. The root of the issue is environmental and collective. It is not so much a decline of the cultural specimen but a decline in the cultural ecosystem. Okay, but analogies aside, what does this mean?

We should start with the observation that good art (and good cultural texts generally) do not emerge from nothing, there is an environment that facilitates their growth. This is a bit counter-intuitive for modern westerners who have been trained for centuries to focus on the producer-consumer relationship. We like good art, we pay artists for their good art. At some point in this process we start receiving bad art. What’s the problem? The range of correctable issues seems pretty limited. Did the artists suddenly become untalented? Did we ask for the wrong product? Maybe the issue is further down the supply chain. Did the artists miss their shipments of precious imported Japanese brushes or super special Mongolian paint? Really, once we think about the problem this way, it's hard to think in a different direction.

But perhaps the issue might become clearer if we use an analogy to the realm of agriculture. For instance, imagine that every weekend, I, city-slicker Dave, bike down to my local farmer's market. I buy a box of premium heirloom tomatoes from my favorite farmer, Farmer John, consume these tomatoes, and am thoroughly satisfied with their superlative quality. For thirty years the pattern persists, and then one day Farmer John shows up to market empty-handed. Almost no tomatoes this season, and the ones that made it to market are sickly and sour. What happened? The weather hasn't changed so that couldn't have been the issue. Did farmer John forget how to farm? Did he lose his seed stock? Did the gods decide to smite him for his impiety?

Actually the problem we are facing in this analogy is literally deeper. Thirty years ago Farmer John inherited the farm from his father who grew Siberian Pea-trees. Looking to do better financially, John plowed the field under and replanted his famous, highly profitable, heirloom tomatoes. Everything went well on the surface, but now, after 30 years of a mono-culture, the soil is completely depleted. Nothing grows, least of all his famous heirloom tomatoes. Time for a crop rotation? I suppose. But the land’s ecology has gotten so bad that even the old pea plants won't take root. The whole field has reverted to wilds, packed with shrubs and whatever sickly crop plants still exist on the vanishing amount of fertile soil.

And a kind of analogous cultural ecological collapse might be what we are seeing in 2021. Just like plant-life, art does not simply emerge from the ground ex-nihilo. It relies on a substrate of common heritage and history, a “folkway” as people used to say. At base this is nothing special. We are simply talking about the common memes and cultural literacy that define a particular time and place and connect it to its common past and future. This is the circulatory system that transports concepts of "meaning" to the core tropes people use to populate their imaginations. Creative types, be they genius or hack, are fundamentally participating in a dialectic with this substrate, recombining, restating, critiquing, taking steps, or sometimes leaps, forward. The process of artistic creation may appear to be entirely individualistic, but there is an essential collective component here.

As even the ego-maniacal Richard Wagner understood, an artist requires a folk to be his audience. Artists are in a larger conversation with a culture, but they also have an audience with cultural assumptions. To really have an impact, a creator requires patrons with access to some common symbolic language, hence folkways and folk culture. In a way, we might understand these rather abstract notions as an invisible hand that aligns the interests of cultural creators and consumers just as the market aligns the interests of producers and buyers. Remove the invisible hand and there is an information asymmetry that prevents anything from getting accomplished.

Does this idea sound crackpot? Perhaps. But I think we can witness the concept at work, even in our own consumption preferences.

Just look at any of the things that you think are cool. In all likelihood, if you think hard, disembodying yourself from your own culture, you will realize that, in addition to being cool, they are also pretty stupid. And just so you don't think that I am picking on you, let’s examine three stupid things that I think are cool (ordered from most-boomer to most-bugman): 1. Bob-Dylan, 2. the Siege of Minas Tirith from Lord of the Rings, and 3. the Space Marines from Warhammer 40k. Every one of these things is cool. Every one of these things is also pretty stupid.

Why don’t I see Bob Dylan as a frumpy folk singer with a frog voice who just happens to write better-than-average song lyrics? Why don’t I see the Orc Siege of Mina Tirith as a silly monster-fight just as goofy as any B -movie gimmick? Why do I not see Warhammer Space Marines as he-man clones in steel underwear fighting battles that make no physical sense, even to people who don’t understand physics? Well, in all of these cases. it's because these things fit into a folk pattern (or as they say these days “trope”) that allows them to be more than their mere forms. They contain something ancient, something that might point to deeper meaning, and something that might point to a deeper beauty.

Behind the image of Bob Dylan lies the ancient trope of the Troubadour, the wandering poet who finds capital "T" Truth just by being present and observing his times. Behind the image of the orcs at Minas Tirith, there is the dark image of the wild-man, Shakespeare's Caliban, the skulking Grendel of Beowulf, and the eternal battle between civilization and chaotic barbarism. When we see a Space Marine, no one sees an actual "space marine" (what the hell could “space marine” even mean?). Instead, we see the trope of the knight, the paladin, and the warrior priest who brings order into the wilderness, sometimes conquering it, and sometimes, being conquered by it.

This process of integrating specific culture into a folk tradition isn’t necessarily conscious. In fact, most of the time it absolutely isn’t. But nevertheless we are making these connections inside collective context, and these things that we love would be meaningless without the historical folkways in play. That is what gives them their gravity, their emotional resonance, and their staying power.

Of course none of these observations are new, not even on YouTube. In fact, I have them repeated back to me by the YouTube-auto-play algorithms' darling, Dr. Jordan Peterson. From Peterson, you can learn all about this common Jungian collective subconsciousness and its role in pop culture and traditional culture. In other talks by Peterson, you can also hear many lamentations about the present state of our culture; the danger of creeping censorship, the lack of imagination and drive, people preferring indulgence to self-improvement. But throughout all of this, I have often wondered why the good Doctor doesn’t integrate these two concepts in a way that is more focused on the collective nature of the problem. Might we imagine that the problems that pervade our post-liberal post-woke world owe in part to the erosion of a common collective archetypical (some possibly Jungian) consciousness? For all the hours of Peterson content auto-played into my ears, I have never heard the good doctor focus on this particular way of conceptualizing the problem, and that’s a shame, because it seems to be the perfect framework we need to understand where our culture is going.

From where I am sitting right now, our society’s decline is impossible to understand outside of a view of some cultural ecosystem, some common folkway, or collective spiritual consciousness that once inhabited the West. And looking at our situation from this perspective, we see that our circumstances are quite grim.

Not only have the old regional ethnic traditions of kith and kin long since been vaporized by the early 20th century nationalist and socialist projects, by the early 21st century the core cultural substrate of religion and broad ethic identity is waning before our eyes. Witness the rise of the "nones", the post national man, and the "citizen of the world" (who always seems like a citizen of nowhere). Welcome to a world where most people have no contact with any identity even remotely connected to something their parents or grandparents would understand. Welcome to planet bugman. And in the place of deep common collective culture what remains? Mass-market pop culture, consumer identities, and fandoms. And even in these completely shallow communities things are falling apart.

Whereas once even consumer identities were somewhat connected to a core set of cultural experiences, this loose connection is fading. Likewise the remaining cultural elements with some innocence or gravity still present in modern entertainment products are being stripped away, and a barren dessert of naked corporate cynicism expands before us. In the final stage, our mass popular culture is descending to lowest-common-denominator trash equipped with hollow narcissistic themes, unnatural fan-fic-tier writing, and banal on-the-nose political messages incapable of reflecting any lasting theme that will survive the next political realignment. Everything is owned, all the area for expansion is staked out, and nothing good, true, or beautiful is being produced.

Is this analysis too abstract? The thing is, even if I turn away from my broader suspicions, I come to a similar conclusion about the state of popular culture every time I think deeply about why some common genre, so popular and effective at communicating meaning in my youth, now seems hollow in my maturity.

For instance, I imagine that it's not impossible to make a good T.V. sitcom like The Simpsons and The Cosby Show. We still have a fair amount of intelligent talented people in Hollywood, and no one ever gets tired of making money on successful shows. But the concept of a family sitcom doesn't really make sense in the present year. The core essence of the sitcom is a lighthearted ribbing of the assumed-default middle American normalcy. The core form of the sitcom is a reaction to an overblown problem that inevitably gets resolved back to the status quo by the end of an episode, thus mirroring the 20th-century middle classes’ perception of itself as silly but ultimately indestructible. By the early 21st century, both the form and essence of this product are missing. The middle American nuclear family is no longer the default reality in most of America, and its survival into the future is very much non-assured. In fact, with the later sitcoms of the early 2000s, the prime target of the satire seems more the sitcoms of previous decades rather than any existing family structure modern people would consider “normal”.

Additionally, I know for a fact there is a great thirst for a science fiction space opera that young men can consume unironically (just like their parents resonated unironically seeing Luke Skywalker fight Darth Vader). Unfortunately, the artists of our age don't believe in unironic adventure. It turns out that there isn’t much left of the "hero with a thousand faces" once you strip away all of the faces of patriarchy. Present science fiction writers can create woke heroes and celebrate their girls-bosses, and the peanut gallery can continue to hurl their regressive “fuck-you”s back at them, but in this process there is no depth, there is nothing really to believe in. In fact, even the artists who create the new and improved progressive remakes don’t really seem to believe what they are selling.

And finally, for those fans of folk out there, while I do believe there is a great work of rural poetry or music waiting to be written about the decline of middle America in 2021, it’s almost impossible to imagine the artists or the audience for this text. Unlike the 1930s, music (let alone poetry) is no longer the language of our plebeian heartland. Furthermore, I don’t think our modern musical elites (either in Nashville or New York) are champing at the bit to produce a new tune taking aim at the "Demon fentanyl” and the “Devil Porn Hub" as their depression-era predecessors described the vices of whiskey and bootlegging.

Perhaps this is a little anecdotal, but the common pattern remains. There are interesting things to be said, but no one wants to say them. There are interesting messages to be proclaimed, but no one wants to hear them. The artist and the folk are tuned into different radio frequencies and the only communication which remains is an endless stream of shrill vanity on one end and simmering silent contempt on the other. Again the problem is not on any one side of the equation, but in the decline of the medium that once connected them.

For us dissidents these cultural problems always seem like an opportunity. After all, we say that the key to moving forward is building things, we think we have a more realistic, more truthful perception of the world as it is. Perhaps we could start with the truth, and then move it slowly towards an expression in art and culture. A lot of people want this, I want this, but to date there has been a notable lack of progress. For whatever desire for dissident art exists in the early 21st century, it certainly hasn’t produced much.

Some of this is forgivable. We are talking about dissidents after all. There is fleeting organization, no funding, and little support. It’s really not fair to ask for something big. No one is expecting a nationalist version of "V for Vendetta" or the NRX version of Toy Story, or a Landian version of Game of Thrones. Still, some amount of underachievement needs to be owned and solved. We all want a certain type of deep culture, a certain foundation on which we can express ideas and a poetic understanding of the universe. But this is not forthcoming.

I am not saying that people don't produce things, I am not saying dissidents don't make content. We all make content. We all have our music, our web-comics, our role-playing games, our blogs and our vlogs. But at the same time, a core culture hasn't metastasized. I know many people who write novels and build brilliant fantasy worlds. Some of them are quite good (if the Franklin is reading this I have a 20-spot waiting for when The Wards of Ensi finally comes out in print). Yet even inside dissident circles, some key infrastructure is missing.

For instance, I can't remember ever finishing a dissident cultural project and then going out to discuss the characters and themes with other fans, as would be typical with other more mainstream cultural work. Even for smaller franchises and cult phenomenon this is weird. In the earliest days of the internet, when everything was fringe, people would talk endlessly about the stupidest web-comics and jokes. Why has this suddenly changed? A critical part of the equation is missing, the collective side of the equation.

True community is absent. The commonality we have currently is driven by political gripes, and everything else is disconnected. If I were to put this in a more solution oriented way, the sub-culture lacks a certain critical mass or critical energy. Stories get written, less frequently read, even less frequently discussed, and almost never iterated on. Without this iterative and reflective dialectic, which we used to expect from our culture, there is no opportunity for any given text to grow into a larger reservoir of shared cultural language.

I know, it's still early days. The post-left / dissident right hasn't even really felt out what it is. But for everyone who has been doing this for a while, we really need to focus on the next logical step. If the only nice things are the things that we can build, what, might we ask, would be worthwhile to attempt to build? What even can be achieved with the tools that we have before us? And how can what we build burgeon into a larger community of creativity and imagination?

Part 2: The Shared Extended Universe and Its Discontents

I am sure from this point we could take many tracts, but for this letter I want to focus on a very persistent desire, deeply felt by many in my own generation: the desire for a fantasy or science fiction universe insulated from political wokeness and able explore new ideas independent of mainstream pieties.

And odds are, if you are like me, or if you belong to a generation older than generation-X, you understand this desire. In fact, there probably is some fictional world that possesses your imagination. I myself was lucky enough to miss the Star Trek and Star Wars crazes, but the Warhammer and Tolkien bugs hit me hard. Derivative or not, it doesn't take much for me to pick up a book or game that takes place in one of these universes, even if I know it is, by some objective standard, bad. I am that bastard from college who convinced you to read Children of Hurin until you realized that it was Beowulf with Elves and Balrogs. No apologies here, Children of Hurin is good, even if it is, well, bad. The goodness of the initial text sometimes isn’t even that important, the goodness of the universe can be enough. One feels a sort of gravitational draw towards it, one is in love with its feel mythology, its shine, its lurking emotions, never quite expressed.

Yet at the same time, these fantasy and science fiction universes are the bane of dissidents. All of them have their origins in some text that is thoroughly reactionary. Almost all are now corporate intellectual properties kept alive by the effort of an older and dedicated fan base. All are now ruled by a myopic corporate and activist class that care more about political messaging and profit than the coherency of the product. The result is not hard to predict, an intellectual property slowly moving away from its core utility, still kept in its place of prominence for as long as its inertia lasts.

But for dissidents, what's most ironic is that the creation of any specific extended universe remains something less than a staggering achievement. In fact, creating new extended universes is quite easy. A brief survey of the popular IPs demonstrates the proposition. Certainly, things like Dune and Lord of the Rings are the product of outstanding genius, but these are exceptions. For the most part, popular franchises: Star Wars, Warhammer, Dungeons and Dragons, are entirely derivative remixes of older material iterated forward by corporate focus groups. In fact, this process of extended universe building is so straightforward that it is literally sold as an entertainment product. A whole range of role-playing games exist to walk the average buyer though this process of creation step by step. And worlds produced by this process have been recycled to produce new corporate IP. This can’t be that hard to do.

And yet the media landscape always looks the same. A few big players dominate our imaginative space, every one of them managing an older "universe" which they didn't create, and are slowly driving into the ground.

At this stage, everyone reading this letter is thinking of a solution, probably the same solution: a solution I heard most recently from my friend and fellow YouTuber, Morgoth, on a shared podcast. Briefly stated, given that everyone on the right-wing is looking for a common environment, why not build our own shared extended science fiction or fantasy universe? The universe might be totally original, but it wouldn’t need to be. It would just need to be a place where dissidents could explore ideas fully in communication with the human truths that we can see so readily. It would just need to be a Fantasy realm of our own.

Again, this isn’t rocket science, we are simply proposing what a thousand other companies big and small have already accomplished with a minimal amount of investment and inspiration. Just like Warhammer, just like DragonLance, or even Homestuck (please don’t click on this link). Not much is required; a common canon, a set amount of rules that govern the universe, and then an infinite sea of possibilities for the creation of short stories, art, games, and shared memes that can develop an imagination completely separate from woke entertainment-capital.

And I admit this is a good idea. It does strike me as achievable. People can realistically imagine something like this happening and people can realistically imagine something like this being great. I suppose this is why this proposition is so frequently suggested and greeted with so much enthusiasm when suggested.

But good idea or not, for whatever reason, people never want to take the final step and pull the trigger. Why is this? In short, it’s because while the idea is romantic, the implementation problems are decidedly unromantic. As such, while the problems are very solvable, discussing their implementations ruins romance endeavor, and therefore no one really wants to address them. But if we are really interested in this project, not just interested in dreaming about it, perhaps we can take the next step and confront the barriers in place? In fact, the problems aren’t even that numerous. There is really only one big problem, one big unromantic barrier to success.

Perhaps, to illustrate this big problem, I can just describe how conversations around this “Shared Extended Universe” usually go. For example, following my recent discussion on this topic with Morgoth, I did receive a large number of communications looking to volunteer on a project to produce a new shared-extended universe. People were enthusiastic, they wanted to take the next step. Pretty good so far! With so many volunteers we should be on our way to starting something and breaking ground!

But, before we go further, let’s take a look at those volunteering more closely. They usually follow one of two distinct forms which I will reproduce each here with a little exaggeration for the purpose of illustration.

The first type of volunteer offer goes a little like this:

"Hey Dave, I really like your idea of a new shared science fiction universe. In fact, you might be surprised to know that I have been working on just such an extended universe in my own time. You will be happy to hear that I have an extensive outline of the world including rules for how magic/technology make it different from our own. This universe has fully fleshed out factions and maps. A storied history (annotated in timeline form not a narrative of course!). I have a variety of world locations worked out, descriptions of various races and nations, profiles of the people and legends that occupy and define the world. Really, it's all ready to go! All that I need at this stage is a group of creative authors and artists to flesh the thing out and build fun content around the setting which I have designed, I need artists to create the art, and write the stories. Perhaps even a game-dev to engineer game systems that can bring this fully realized universe from my notepad to a medium ready for consumption. When are you available to talk about these implementation details?"

The second type of volunteer offer goes like this:

"Hey Dave, I am a skilled artist who can construct fully realized and realistic fantasy art with long work experience producing content for publications. I also am a writer capable of generating long well written prose with well-developed characters, suspenseful plots, well described settings, and memorable twists with poignant themes of deep human relevance. Furthermore, in my spare time, I develop well-balanced games (both digital and tabletop) with innovative and and balanced game mechanics that keep players coming back for more. My one problem is that I just can't seem to think up an extended science fiction or fantasy setting to contain all of the content I am generating. I have a total inability to draw-up outlines of factions, construct maps, recombine themes from past science fiction or fantasy to bring a new world into being. Do you know of anyone who might be in the process of constructing such a universe who could tell me exactly what I can and can't write about, draw, or design in my game? Again, the person I need to tell me what to draw and write doesn’t have to be you, or any content creator who I actually like, it can be any random person who wants to outline a universe. Without this input I am really lost going forward."

And indeed, you can can see how these two sides of the coin work together to build a shared fictional universe....Oh wait… snap! I am just checking my notes and it turns out that I have never gotten a message of the second type, just messages of the first type. There seems to be some asymmetry in demand for roles here.

Like all collective projects, we have run into the classic problem of communism. Every one is signing up to be ideological commissars, no one is signing up to be a toiling proletariat. Too many people want to design the universe in broad strokes and control its outline in at the top level, too few people actually want to populate the details of this universe with their focused effort, skill, and time.

And before I get too ahead of myself, I want to be clear to those who wrote to me. I get it. In fact, I more than get it, I am one of you. I too have have outlines for science fiction and fantasy universe scrawled out on notebooks locked way in the back of my file cabinet. I too want to see my vision given life by skilled artists and storytellers. I want to be the one in control of a new shared universe. At the same time, do I really want to build every element of it? Do I want to write books? Design games? Create art? Do I even have the time? Well, not unless you pay me enough for this to be my fulltime job, and I do have a YouTube channel and child to occupy my time as well.

Again, I am not trying to be rude, but I need to be blunt about the bottleneck here. I know the people who are contacting me are highly creative people with detailed universes. I know that most of you aren't untalented. I know you probably have skill in writing. You may even be a talented artist or game designer. And I know that managing a world (GMing as it is called in roleplaying) is hard work. For sure, if you were managing an IP with an established market presence that millions of people loved, ensuring consistency, continuity, and clearness of theme (the exact thing modern IP owners AREN'T doing) this would be an enormous contribution. But in the context of a start-up project with no pre-existing content? The situation is much more delicate.

While GMing is an art of sorts, it is an art that only a very small number of people do well, and most of the people who think they do it well don't actually do it well. We all have memories of bad roleplaying sessions among friends. Everything is going well and then some super silly element is introduced into the plot that just ruins the illusion. For the most part we roll with it because we are friends and because we are playing a silly game. But while putting cringe plot elements into a created universe is very forgivable among friends, it’s lethal to a project that ties together many disinterested parties who don’t actually know each other. One silly name or goofy alien race introduced to an otherwise serious universe could cause a ripple effect of people leaving the project due to a conflict of creative visions.

As it turns out it is exponentially easier to ruin a shared project through mismanagement than it is to build it up through the arduous creation of its core content. And people understand this dynamic, revealing it subconsciously with their preference to manage a shared universe rather than contribute to someone else’s.

And, if you are not convinced, we can test this. If you are a creator who likes the idea of starting your own extended Fantasy or science fiction universes, how willing would you be to spend a serious amount of time writing a short story in another person’s extended universe? Not my extended universe. Not some YouTuber who you like, just an anonymous internet user who provides a set of rules and tells you what you can and cannot include inside your own stories. For those of you who haven't written fiction, remember these projects usually constitute 1-2 weeks of free time if you have a job and a family (unless you are a much faster writer than I am). And remember, when you submit your story, the GM can always nix it because the story doesn’t fit the thematic “feel” of the universe. Did I mention that you don't know this person or have any experience of this universe beyond a design document? You aren't a fan who loves an existing game or movie, you are just volunteering, volunteering in essence, to have a boss for your creative expression. Let's just say that I am not surprised that there is a lack of takers for this proposition.

Certainly, some solutions to this problem naturally propose themselves. Everyone has their own universe, so why not merge them together? Why not have a giant group zoom call with everyone interested, make compromises until all the different visions can fit into one pot, and then go forward? That is the democratic way. Instant success!

Of course, no one who understands anything about real politics or human social organization could ever think that this would work well. The result of this process, the process of merging many creative universes together, has only two possible outcomes, neither good.

Under the first possible outcome of a “collective design”, the number of designers making significant inputs remains large, which means, in essence, that we have transformed our extended science fiction universe into a committee project, defined by what many people want and can vie for politically. Knowing how these things go, after concordance, the document describing the project will likely be novella sized, filled with an enormous number of rules (some contradictory), and will probably not even be fully conceptualized by any of the people who put the document together. If you thought adopting someone else’s universe was like volunteering to have a boss, how about volunteering to have 20 bosses? As they say, out of the frying pan and into the fire.

The second possible outcome of a “collective design”, is the exact opposite of the first, instead of many creators making significant inputs, there is a gradual narrowing of scope until only one or two people are actually in charge of describing the project with most other volunteers leaving or falling silent. Of course in this scenario we are pretty much right back where we started, with one central GM of the extended universe. So what was the point of the collaboration to begin with? The one or two last men standing could have just collaborated. In fact, post-coordination, they are probably at a disadvantage since the process has likely alienated many other creative types who had their cherished ideas vetoed. Slighted creative individuals are less likely to be part of an enthusiastic volunteer base going forward.

The problem with creating a shared extended universe for fiction is the classic managerial problem called "too many cooks". Two authors is rare enough. But when you get to three or four? Forget about it. I have never seen a remotely coherent fictional work authored by more than three people. And this problem doesn't get better once you expand the question out latterly.

The difficulty might appear strange enough because our problem seemed so simple from the outside. However, when we examine large extended universes in the corporate world, we are witnessing an illusion. Products like Warhammer or Star Wars maintain their coherency through a connection to a core set of outstanding copyrighted products that already generate millions of dollars and fans. These extended universes also have the advantage of having entered into a marketplace that was relatively underserved for its time. The fortified a semi-monopoly of secure profits sheltered these corporate products from having to deal with real problems and real politics, and even this advantage was ultimately short-lived. Whereas initially management was able to insulate its core product from the thousands of voices who wanted to ruin it for purposes of vanity (personal and political), now even the most conservative properties are succumbing to the corrosive nature of group-think. Politics is the universal degenerative gravity that inhabits all creative projects, money and power may defy it, but only temporarily.

So then, is the idea of an organically derived "shared extended universe" completely off the table? Well no. But here I think we must discard the most obvious approaches. The portion of broth we want is too large for one cook to make, and employing multiple cooks will inevitably spoil it. But what other option could there be? Perhaps a solution that forces us to reconsider how we think about authorship and cultural creation to begin with?

Part 3: Engineering a Cultural Permaculture

The problem we encounter, every time we examine a collective project of this type, originates with our concept of authorship. This issue goes to the heart of what we call intellectual property (referred to through this letter by its corporate acronym “IP”). Certainly, a library could be written on the flaws of intellectual property, but here we only need to be concerned with one faucet; namely, the limitations it imposes on collective creative projects.

Critiquing IP is difficult, it’s hard to stand back and really get an understanding of the role it plays in the modern world, harder yet to imagine an alternative. Yet this approach to culture is relatively new. Our modern understanding of intellectual property, formally attaches a text to an individual. Through the magic of incentives (both prestige and money), the concept incentivizes authors to the task of making better and more note-worthy art. If one wants to be recognized as an artist who matters, they make texts and become identified as the author of said texts. By this attribution the artist’s name is made and he exerts "creative control" on his product either by influencing its further development or, at the very least, by managing its interpretation. Authorship and IP is the prestige of the artist, and their use incentives a general desire to create new and better things.

And we must admit, straight up, this system works. It works very well with one author, somewhat less well with two, and almost never with more than three. But the system works. And it keeps our idea-economy going. But things were not always amenable to this approach, and in fact, they may need to change again radically if we want something new to emerge.

Like so many things that once worked in modernity but don’t anymore, the problem with our IP system is that it presupposes the existence of an infrastructure that has since been eroded and cannot be rebuilt by the system itself. The only recourse left to those who want something new is to return to the source of our error, correct it, and move forward in a completely different direction. But given how long we have been enthralled by these notions what would an alternative even look like?

If we look back to premodernity we see that culture and art (some elite variants notwithstanding) was not conceptualized in terms of strict authorship. People played their own music, crafted their own art, told their own stories and used each of these texts in turn for the purposes required. Who authored this folk tale or song? Very few people knew or cared. Of course sometimes specific folk poets and artists put their names on things, but even here, it's amazing how many works simply don't have clear attribution.

For instance, the most famous work of the late Renaissance musical tradition "Greensleeves" doesn’t have a clear author. We might think that the Brothers Grimm wrote “Hansel and Gretel”, that Robert Tannahill wrote “Blooming Heather”, that Dick Dale wrote the “Miserlou”, but this belief is false in every case. These works came into being in their most primitive forms, with essentially no author. Well, perhaps this is a bit of an over-statement. These texts were the work of human hands, therefore they did have authors. But if we tried to construct a bibliography in a modern-IP sense it would span hundreds, if not thousands, of names. Sometimes, these names are grouped under the moniker of the last person who vivified the text (as in the Brothers Grimm or Homer), sometimes not. But for these authorless texts one important thing remained: no person could exert political control on the text or corpus; not in person, and not in the form of an estate speaking on behalf of an intellectual property. These works, were (and for the most part are) zero-author. They were folk culture.

The core issue with building a collective piece of culture (or folk culture) is that we are trying to use the tools of modernity to fix a problem that modernity rejects. We need organic culture, but the framework of modernity rejects the organic because it has no way of understanding organic texts outside of a concept of property. As modern people, we look through the lens of our technological age, we view the problem of collective creation (even the collective creation of folk culture) as a variation on the question of corporate production. Are many people working together to build an artistic text? That means there must be many authors! But this is the opposite conclusion we should come to.

Authorship means property, property means control, property with more than two authors means disputed control, disputed control means politics, and politics is the death of creativity and cultural life. No, any shared large-scale collectivized project should not strive to have many authors, or even one or two. It should strive for ZERO authors. As many authors as “Hansel and Gretel” has, as many authors as “Blooming Heather” has, and many authors as “Paul Bunyan” has. Zero authors. You can't beat it. A complete absence of political control is the only way forward. No one dictates the artistic vision. No one’s ego is at the center. No one sets the bounds for the mythology. The project evolves through the organic cycle of creation-mistake-revision iterated again and again, strength through evolution, not design.

To return to our agricultural analogy, what we are doing is shifting strategies. As opposed to finding the strongest pea pant to muscle out the weeds and start a new rotation cycle, we are simply clearing a space, mulching the soil, simulating an artificial ecological reset (that would have occurred had the field been left to fallow), and then seeing what new non-weed plants might thrive in the new environment. With enough time, water, and some corrective weeding, we will find the strong plants that can recreate an ecosystem previously lost to poor stewardship. The trick remains to minimize assumptions about what the environment can sustain, let many different varieties take root, and let the process of regeneration proceed through the adaptive strength of the plants themselves.

What we desire are great artists and great thematic visions, what we want eventually is another prize winning crop. But before this occurs we need an environment that can facilitate creativity across the board in an ecologically healthy direction. The common solution is folk culture. An environment that contains zero-author content that eventually facilitates a common creative language; a corpus of artistic works that may, someday, inspire a broader ecology of musicians, story-tellers, poets, and designers. Ultimately in the future, we hope that these creators may arrive at something approaching greatness, but this is not the state we are in currently. We aren't planting a cash crop, we are just building a cultural permaculture; little improvements, creative safe-spaces that encourage people to experiment with new stories, and more content freed from the stifling political control of the modern world.

But analogies aside, how could someone actually do something like this?

Part 4: On Board Games and Cultural Mutation

Alright dear reader, since I have kept your attention until this point, let's see if we can't write an outline for how such a zero-author collective cultural project could be undertaken. Impossible? No, not if we apply good engineering principles! Principle 1? Start with what you know works. Principle 2? Keep it simple, stupid. Principle 3? Don't reinvent the wheel.

Starting with what we know, what does some modern, organic, zero-author, cultural project even look like? Do we have anything that is close to this in contemporary society? Something specific? Something workable? If we do, how closely can we observe the phenomenon? How does it work and what do its outputs look like?

In the era of social media, I am sure people will have good answers to these questions. There have been numerous Kickstarters that would fit this description, not to mention the somewhat less popular wiki-collective fiction projects, and interactive meta-fiction universes. But in line with our engineering principles, let’s keep things simple. In fact, why don’t we leave behind 21st century internet technology and start with pen and paper? Let’s begin with my all-time favorite table-top board game, hands down. Not Dungeons and Dragons, a game called “Exquisite Corpse”.

According to most sources, "Exquisite Corpse" was invented by the surrealist artist Salvador Dali in the 1920s to escape moments of creative lapse. The rules are simple and the game plays like an extended version of the children’s activity “Telephone”. Starting with somewhere between 5 and 20 people sitting in a circular formation with a strip of blank paneled paper, the game starts with a "caption round" where each individual writes a caption on a panel describing anything. After passing the papers to the next person in the circle, the round moves to a "draw round" where players illustrate the caption passed to them. After the first "draw round", the paper is passed again and folded so that only the drawing portion is visible (obscuring the original caption). In the next round (the second “Caption round), players are asked to provide captions describing the picture without the context of the original caption. From this point rounds alternate between captioning and drawing with each new drawing or caption being based solely on the previous caption or drawing in line. The game ends when people run out of room on their paper.

What is the eventual result of this process? Not a winner certainly, but in any casual setting “Exquisite Corpse” generates a series of absolutely insane comic strips as misunderstandings and misreadings pile on top of sloppily drawn pictures and hastily written captions. Just reading each of the strips and passing them around is usually enough to get everyone laughing and in good cheer.

Alright, so it’s a good group game and definitely something you might try at your next party (do Zoomers even have parties anymore? Is that still a thing 2021?). But actually, if we stand back and examine the process, the general form can be used to much greater effect to drive creativity with a minimal amount of control.

As alluded to in its origin, “Exquisite Corpse” is, at its base, a tool to explore the subconscious imagination. If taken seriously, it can produce new texts completely disconnected from anything that the authors were thinking of before they started the process. As such “Exquisite Corpse” can be viewed as an engine of sorts. Derivative ideas enter in one end, strange re-combinations and mutations exit on the other. We can put the most cliche and trite trash into the input valve of this system (sometimes even literally copyrighted IP!) and regardless, a text will appear on the opposite end as a completely original work, weird, mutated beyond recognition, but distinctly its own thing.

Interestingly enough, “Exquisite Corpse” seems to capture in microcosm the fundamental two-step nature of the human creative process which generally iterates between two poles. First, a process of narrativizing an experience of something we can visualize. Second, a process of rendering visually a narrative which we read or hear through the spoken word. In short, humans tell stories about the things they see, and paint pictures based on the stories they hear. If we link the two processes together we have a microcosm of the process that has generated all folk culture across the ages. For those creative types out there, they will understand the experience. Narrative artists, storytellers, always have their best ideas when they look to nature or at least to something they have witnessed in real life, that strange thing that needs an explanation or story for it to seem right. Visual artists have their greatest inspiration when their mind’s eye is captured by a good story, asking themselves what it would be like to see that great man in the flesh, or journey into that landscape they once heard about in a tale.

In short, folk culture, at its simplest, is the process of iterating narration and rendition. But instead of waiting for this process to take place organically over the course of decades (or even centuries) the engine observable in “Exquisite Corpse” (what I call “The Exquisite Corpse Cycle”) forces it to operate over the course of 30 minutes in an incredibly narrow setting, accelerating it to a ludicrous speed to create the kind of autonomous and spontaneous cultural mutation which makes the activity hilarious. That’s good for a game. But perhaps we could vary these parameters for something larger in scope?

Returning to our original problem. What we are now looking to do is to create a chain of linked texts each of which can be used to inspire future more original endeavors going on down the line. OK, great. But how does this differentiate our project from culture in general? I mean certainly, all culture iterates. So what are we really learning from our example? Well several things.

The main objective is to accelerate the iterative process and drive it forward with a certain amount of rapidity. To this end the presence of intellectual property is the main obstacle. We need to limit the amount of politics that occur over questions of how artistic work is used. And ultimately, if this first part wasn’t hard enough, we need to create a minimalist review system to control the results and drive the process towards a certain predetermined goal. Both of these requirements are a part of the game "Exquisite Corpse", but outside of the parameters of game rules we need to become much more specific.

Any type of folk-culture generating system needs to have separate standards of intellectual property, legally and culturally. Anything that goes into a folk culture system needs to be shareable with minimum requirements for attribution (for those legal nerds that's CC Attribution 3.0). Authors can take credit for the things they produce, but they cannot exert creative control over future products based on the texts already created. Remember, this is a zero-author environment, and if things are proceeding as planned, while the individual texts are likely traceable to their original authors, the general emergence of themes, aesthetics, and perhaps even settings and characters might be more vague.

Furthermore, there has to be an understanding that iterating or copying (with attribution) is perfectly fine with no exceptions. For instance, for those creative types out there, how many times have you come across a product that you loved except for that one little piece of it that you thought should have been left out or modified in some way? Well, you are in luck, under this system ANY change you make, no matter how minor, is legitimate. Everyone can issue abridged forms of their favorite stories, anyone can make their own “audience-member-cut” of their favorite film. Of course, we can't promise that anyone will read, watch, or promote your updated version. And there may be incentives to ensure that there isn’t a level playing field between the original work and derivative copies with only cosmetic modifications. But still the principle applies. Sharing for the purposes of iterations is paramount.

If you have been reading this so far you are probably waiting for the other shoe to drop. After all, I might be a crackpot but I am not naïve. What I am describing here is one requirement of our system. At this stage I am trying to remove barriers to iteration. But all I have really done is put a burden on the creators themselves. I have asked artists to give up creative control. And for what? So that their rivals can better use their products to beat them out in the long run? Furthermore, this is modernity we are talking about, right? I mean, in previous parts of history people lived in close proximity, folk culture was created, congealed, and became coherent, because people had to tell the same stories and sing the same songs. It came out of necessity. Well, that necessity isn’t here anymore. And unfortunately, since we don't have any other tools available, this absence will have to be compensated through crude management.

To borrow the immortal phrase of Captain Jack Aubrey “men must be governed”, and so too must collective projects. If we want people to write they need to have goals, they need to have standards, and they need to have incentives through finance or recognition. And this process will have to be managed and governed carefully.

This is the hard part because it seems that we have just reintroduced the very problem we were trying to remove, namely creative control. How will a management system work to keep everyone working towards the same goal while not becoming corrupt and ruining the creative process?

By setting up this management carefully, with a minimal approach, and with clear rules. The management system, which we might call “the board”, should exist for the sole purpose of representing the interests of the consumers who will eventually read, watch, play or otherwise enjoy the texts created by our iterative process. For this purpose the board acts only as a communication bridge and overall steward, focusing consumer interests, making clarifications based on what is desired, and driving the fulfillment of this desire with financial incentives.

This is not a small job. The board will need to take the temperature of what people want, configure it into digestible prompts, attach incentives, recognize winners, then iterate the process forward (possibly shifting the medium to obtain the narrative-rendition cycle seen in “Exquisite Corpse”) all with as little impact as possible on the creative process. For this purpose the board would have to be anonymous and unable to exert control outside of rules clearly laid out at the start. The critical requirement is that none of these board members should be linked, in name or in social media account, to the collective production itself. I am not saying that this needs to be airtight in any sense. But from the outside at least, the project cannot seem to be "so-and-so's pet project". The board is in the background, the ones who keep the game going, they are the referees. The people who chose to submit content are the players, they are in the foreground, they are the authors contributing to a collective project with no visible overall author.

From this point on, we might imagine how the general process would go. We start a board with some initial investment capital. The board comprises a small set of interested individuals who agree to an initial plan (board charter) and submit all of their decisions to public record in a documentation database (like a wiki page). What proceeds in turn is the polling of a customer population to see what its general interests are, combining these interests (with some existing IP) into a core initial prompt, and then soliciting content creators to submit work within the bounds of that core prompt. Based on the prompt, the board receives texts in line with their requirements, establishes property for sharing purposes (permission to iterate, share with attribution-only, etc, etc.), and rewards high quality submissions with incentive prizes and promotion. After each step, all submitted work is then archived in the database (which future artists are free to iterate on) while the board considers the next step to encourage the development of incentive for more content based off the popularity and quality of the work received.

Still too hand-wavy? Let's work out an example from the beginning to demonstrate proof-of-concept. We can call this prototype project the "Exquisite Corpus Project" based on our initial idea of building a shared extended science fiction or fantasy universe that dissident people can use for their creative writing and role-playing purposes.

Part 5: “The Exquisite-Corpus Project”, A Prototype

What follows from this point is a white paper concerning the use of the previously described method to produce a zero-author fictional extended universe. All details provided could be implemented by any medium sized dissident community online or off. Each step is outlined in detail with directions to the following steps included. Once more, this document is not designed to be an actual project proposal, but is rather a prototype, a rough draft for people interested in doing something similar in the future.

Outline of the “Exquisite Corpus Project”Step 0, Establish board, funding, and core charter:

The first step is to establish a board with a basic understanding of the project objectives and constraints. The objectives need to be established ahead of time and with complete buy-in from the prospective members of the board. In our case the mission statement can be written as follows:

"Create a Gothic science fiction universe with a core canon, a range of new short stories, art that illustrates the world, and an outline for prompts that might inspire further content creation while avoiding woke/progressive political themes."

Pretty vague, but necessarily so because it isn't the board’s job to define the universe, just to characterize the demand for the universe. Core qualities will then be formed by the creators themselves as we proceed through the steps outlined. However, before anything else is accomplished, ground rules must be established for the board itself. An example board charter might look like this:

- Board members are not creators or authors of the “Exquisite Corpus Project”, just managers and quality control referees that represent consumers’ interests.

- The board is responsible for publishing core prompt documents to solicit the creation of quality texts, and publishing "retro-continuity (retcon) documents" that highlight the best submissions and discuss their integration into the project (shared universe) in a way that maintains their coherency and continuity with other submissions.

- The identity of board members is closed to the public, communication with creators outside of prompts is strictly prohibited.

- Board members can submit work to the project as creators, but may not disclose their presence on the board as part of that process. However, board members cannot receive any prizes or recognition for submitted content.

- Board members may use polling and market testing from an audience, all poll results are public, but the board is NOT required to act on any results they receive.

- All board decisions are run on super-majority, board staff circulation is acceptable, but the board should never exceed 5 members.

- All submissions to a prompt are public and held under CC 3.0 share-attribution license.Starting from this foundation, the board opens a funding source (bank account linked with SubscribeStar, super-chats, or Kickstarter), and a database wiki with the rules and charter listed in an "about section". This gives the basis for moving forward, including 1. core seed money, 2. a centralized public database with space for dialogue, and 3. a core charter to control how the board manages the project.

Step 1, Test customer base and search for art:

With the basic rules established, we need to start putting flesh on the bones of the project. Once more, we want as much of this information on how to do this coming from outside the board. This starts with some basic brainstorming exercises where a friendly audience is asked to contribute blurbs concerning what they would like to see in our new shared-extended universe. All of these comments will be posted anonymously to some centralized database thread that can be archived. Really, I am not anticipating many speed bumps here. If past experience is any test, people are forthcoming with small pieces of feedback which don't require focused effort or attention. For instance, if we were to float an idea of a new extended science fiction universe, we might expect the following comments:

“should have political intrigue and suspense"

"should involve conflict between religious factions / philosophical themes"

"would want to have conflicts between different alien groups"

“aliens are overused, please have this be a human-only space drama"Again, none of these concepts is particularly original. They aren't even coherent. Obviously choices will have to be made. But since incorporating any of these ideas into a prompt is optional, board members can always stop reading if they are pressed for time. The process works as long as there are enough core ideas to form a very basic guiding vision for the rest of the project.

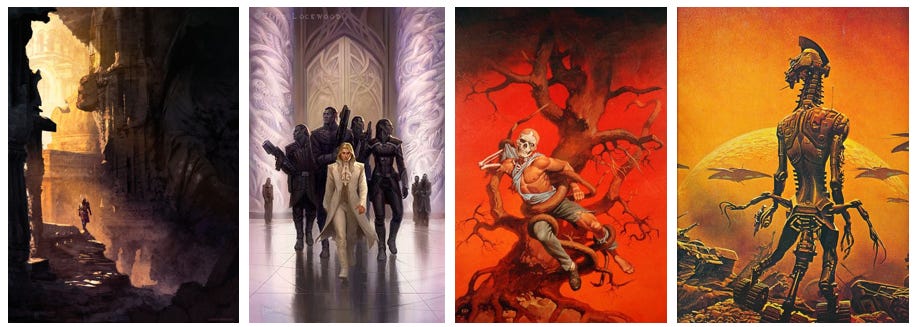

The next step, perhaps counter-intuitive, is doing an "inspirational" vision search. After reading and understanding what the core audience wants, the board directs its attention to some image aggregator site like Pinterest (or perhaps a less pornographic styled version of Deviant art). The purpose here is to look for pictures that communicate the mood of what people want, the core artistic vision that could inspire people to tell good stories. With luck, none of the picture will be easily identifiable as a well known IP (even if they do come from a universe that is owned by a corporation) and the original source of the art will be cited on the database.

Of course we should note that these “vision images” will obviously not be considered part of the core output of the project, but at this point we don't care. Generating our own art will come later. At this stage, what we are looking for is simply something visual that will inspire the first round of storytelling, and this can easily be found using existing work.

Step 2, Develop the Core Prompt Document:

Alright, so at this point we are ready to put together the first prompt document, one of the two major deliverables for the board. Critically, the prompt document needs to be clear and succinct. Once more, the board isn’t writing a universe outline, they are just prompting people to create their own universe. This means brevity is very important. In fact, I think there should be really only four sections. The initial blurb, the invitation to submit, the rules for submission, and the attendant documents to inspire and guide people to create successful submissions.

An example document is included here.

Exquisite Corpus Prompt, version 1.0In the distant reaches of the far future, humanity is in crisis. After more than a millennia spreading out across the stars, creating colonies that number in the billions, catastrophe has struct. An enormous inter-stellar storm has consumed the galaxy for two centuries, ending interplanetary travel and sending each human colony reeling through spacetime. Now, with the storm subsiding, the human race has been forever changed with each colony experiencing time differently. For some only a century has elapsed for others it has been millions of years. For those who venture forth into the wilderness of space, a new world of possibilities awaits; for some a look into the past, for others a glimpse into mankind's future. Will humanity find hope among the timeless eons and countless stars or only the horror of recognizing what they never thought humanity could become?

Invitation for stories:

Hello and welcome to the “Exquisite Corpus Project”! This is a new collective science fiction project that we are undertaking to allow creators to build their own worlds inside a new and exciting extended universe. In general we are looking to provide a space that maintains the coherency of a shared mythos with a minimal amount of intervention from organizers to maintain its coherency and quality.

At this time, based on the requirements of this prompt, we are looking for short stories or illustrated stories that tie into our core themes. The top 5 works will receive a prize of XX bitcoin and will be highlighted as part of the core canon of the project going forward.

Notes on submissions

- Authorship is respected and all works are published to our database with whatever attribution the author wants.

- All submitted work will be publicly available under creative common 3.0 share-attribution license.

- Subsequent authors can modify existing work with attribution and links to the original work.

- The judging of submitted work is completely discretionary and involves no hard requirements outside of this core prompt document.

- In addition to prize money, top entries may also have their story illustrated as part of the ongoing expansion of this collective project.

All submitted works will be hosted on our website. However, people looking to submit should familiarize themselves with the listed design suggestions. A strong entry for this contest will do the following:

- Express the core Gothic aesthetics seen in classic science fiction authors like Frank Herbert, Stanislaw Lem, or Gene Wolfe

- Explore core human themes such as the struggle to preserve truth and goodness in the face of strange new technology and biology. The conflict of men’s souls with themselves and their surroundings, etc, etc.

- Maintain a strong character and plot focusing on eternal elements of the human condition

- Explore concepts of culture and religion, along with conflicts in world-view between characters and societies

- Avoid classic science fiction tropes. No easily relatable human-like aliens (like Vulcans and Klingons); call human-like entities ‘human’. No small universes were travel between planets is routine or trivial, avoid any world-breaking technology that obsoletes core constraints of time and space outside of the obvious faster-than-light travel needed to make the setting work (e.g. no easy to operate teleporters, perpetual motion machines, time-travel, or infinite parallels universes that can be used to fill plot holes)

- We prefer a subtle rather than overt notion of good and evil when it comes to human characters. Heroes can be heroes and villains can be villains (and this can apply to societies as well), just don’t have this written on their name tag. Eldritch horror and monstrous forces driving a suspense element notwithstanding. Outside of these design suggestions, we would like to encourage creators to invent their own peoples, planets, and cultures inside the general framework of a larger space-faring galaxy. Due to coherency and continuity considerations, we also suggest stories NOT spend too much time describing the universe at a very macro-cosmic level (this will likely cause continuity problems with multiple entries). Instead, try to focus on a specific planet or set of planets, the cultures that live there, and of course, the plots and characters you are writing about.

Story Inspiration Guide

For the assistance of the authors, we have included some core images below that might communicate the mood (not the plot) of the submissions we are hoping to receive.

For further guidance, we have also included the following prompts we think might make for good stories if followed loosely:

- Two friends meet after a long absence and one has a terrible secret.

- A strange traveler appears on a planet, he is not what he seems

- An assassin works towards the demise of their political enemy, it is all going as planned, except for one complication

- During a locked battle between two space-faring empires, a diplomat works tirelessly to bring the war to a close

- A crashed spaceship on an ancient world is plagued by a horror from the shadows, until they realize where they actually are

- Star-crossed lovers meet and separated tragically. Will they meet once more, against the odds?

- A diplomatic meeting begins between two races and a misunderstanding occurs

- Rebels fight against implacable overlords and learn of a secret that could turn the tide from a mysterious stranger

- An explorer takes to the stars with an intrepid crew to chart an unknown region of space, they encounter something beyond their imagination

- A devious pirate and his crew plan to steal a valuable object from the heart of an ancient empire, can they succeed?

Submissions should be between 10-20 pages (5,000 -10,000 words) in English, please proof read and check spelling for full consideration. Now, this document is a lot of text. But to put things in perspective, it took me almost no time to write. An hour on the outside of things. And I know, it's super derivative. But that's the point. I am not trying to introduce creativity, just trying to inspire it. What I have provided is the sub-textual outline for a thousand science fiction stories. I know Dune did it, I know Warhammer did it, it's a tried-and-true formula. The images used are all stock images you get by entering "Gothic science fiction" into a Pintrest search bar. The suggestions included at the end of the document are the classic short story prompts you will get in a creative writing class.

There is nothing new here, but as derivative as all these things are, they do encourage the creation of passable science-fiction adventure stories (in fact it's hard to find an adventure story that does not fit one of these archetypes). We have created fertile ground and can let the artists take their own flair and originality to this template.

With this document in tow, an aspiring author should have no problem generating submissions. Perhaps this is presumptuous, but writing this prompt now I am tempted to stop, pull up a different document, and start writing science fiction instead of this dry outline for a collective fiction project no one is actually implementing. Does this make the prompt good? Probably not, in all likelihood this initial attempt is weak tea. But I am sure smarter people, with more experience in writing, could do a better job, especially given more time and focus.

Step 3: Determine winners, and attempt to form an integrating narrative retcon

Assuming submissions are forthcoming, it now falls to the board to read and evaluate the work. This is probably self-explanatory, but there is going to be a large range in quality of short stories. The board is required to read submissions, select the elite and pay out prize money (here board members are able to iterate on existing works to overcome core coherency problems with the other selected works). After prizes are awarded, the edited stories are elevated to a front page and become canon for our universe.

Then, from this revised selection, the board begins work on a new “retcon document” to be published to the database. In this recon-document, board members determine an outline of the shared universe, this time incorporating the details they have learned from the top short stories. The retcon document should be short, and provide a sort of "dust-jacket" version of the universe that describes the canon succinctly for anyone coming to project for the first time. This is the blurb that future creators will read when trying to determine if they want to participate. We now have a better idea of the universe we are creating and can take the next step.

Step 4: Purchase IP art for the next round of Seed Stories

Now for the fun part. We just accomplished the narrativizing portion of our project, now we need to move onto the rendering step. This means getting our own illustrations. I imagine this step will be significantly easier. Unlike the first part, where coordinating writers for money is like herding cats, illustrators are usually very willing to work for contract and typically like plugging their imaginations into someone else’s narrative project (at least in my experience).

In fact, there are entire websites where it is very easy to purchase original high-quality art, especially if the work is targeted towards a science fiction and fantasy setting. Just take a budget and buy stuff that looks cool. Make sure that the art illustrates either scenes from the top stories submitted or depicts the broader universe based on the retcon document produced by the board in the previous step. The requirements don’t even need to be specific. You might even be able to give an artist a story and then just ask them to draw something they think might exist in the same universe. Perhaps we can get a bulk rate on illustrations?