Live Your Own Truth: Finding Our Way Out of the Dead End of Propaganda, Mimesis and the Idea of Personal Genius to Begin the Process of Birthing a New Culture

It is vitally important that we learn how to once again "ground" ourselves. But we cannot do this with reason or science. We cannot do it with universals. The only way out is through.

Critical theory. Post-modernism. Politically, these terms spark revulsion in many. They are looked upon as the cause of many of our problems today. Many have the thought that if we could just stamp out critical theory we could get rid of the political movement labeled “wokeness” and things could go back to normal. I wish this were true. Unfortunately, post-modernism, and with it critical theory, are intellectual movements that arose out of the problems created by modernism, by Enlightenment liberalism itself. The only way to properly grapple with critical theory is to acknowledge that in many ways they were right about modern liberalism. But the solution is not simply to get rid of post-modernism because the problems with modernity will remain and similar criticisms will resurface again and again. As the saying goes, the only way out is through.

What got me thinking about this again was a wonderful essay by Duncan Reyburn last week, which if you haven’t read, you should take the time to do so.

Duncan, drawing on the insights of Girard, discusses how removing the boundaries which restrained thought does not actually produce within us the freedom of thought we expected. Instead, when we are not anchored, and limits are not placed upon our thoughts, we become enmeshed in a web of mimetic desire. We absorb and mirror the desires of others. This, he correctly argues, does not lead to the promised emancipation of the self. Rather, it produces a kind of bland sameness wherein we all end up looking, thinking and acting the same. We want the same things. We strive for the same goals. Without limits or restraints upon our desires, we become slaves to mimesis, to imitating the desires of others. Individualist emancipation, freedom from any unchosen bonds, does not actually deliver what it promises. Instead, we become slaves to desire, desires imposed upon us through memetic imitation.

Duncan’s piece reminded me of a lengthy section in Hans-Georg Gadamer’s “Truth and Method,” where he discusses the transition from pre-modern, to the modern, to the post-modern notions of art, meaning and hermeneutics. While I have been strongly influenced by Jacques Ellul, my philosophical core lies with the hermeneutical theory of Gadamer. In “Truth and Method” he takes on the challenge of both modern and post-modern hermeneutics, that is, the question of how meaning is transferred. He makes the argument that an exchange of meaning can happen, that communication is not merely all language and power games, contra the post-modernists. But he argues against the modernists that objectivity is not a thing, you cannot escape your sitz im leben, your situation-in-life, and that sound methodology cannot guarantee that you will arrive at the truth. This undermines both the scientific method as well as the hermeneutical theories of the 18th and 19th centuries. I credit Gadamer for helping me grasp the arguments being made about the nature of wisdom by the authors of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and elsewhere in scripture.

Many don’t know what to do with Gadamer because he doesn’t affirm people’s pet philosophies and his proposals don’t really make anyone happy. Truth and Meaning are real things, but I can’t really give you any guarantees you will find either, doesn’t really play well in today’s politicized intellectual arena. We want tools that we can use to demolish our enemies.

We must cover a lot of ground here in a short space. In a nutshell, the effect of Kantian rationality is that in his efforts to find a rational basis for knowledge, Kant severed the ties between metaphysics and knowledge. Because you cannot logically demonstrate the connection between the things we know and unseen metaphysical categories that were claimed to underlie them, we have to accept that all metaphysical categories cannot be proven, they are simply accepted a priori, that is before we begin thinking. In essence, argues Kant, there can be no proofs for God. Similar to the Platonic forms. In this, nominalism is victorious. The connections between things must be just asserted, they cannot be proven. They are merely assumed. This paved the way for the rejection of metaphysical questions in knowledge. No longer would we ask “why?” or “should?”. Instead, we would just focus on how things work. This utilitarian, rationalist approach to knowledge has been immensely powerful. But, as Iain McGilchrist argued in “The Master and His Emissary,” this focus on rational and scientific knowing has unbalanced us a society.

This also had the effect of undermining knowledge itself, opening the door to critical theory. If all connections, ideas and even morality are simply asserted a priori, how do we know that all knowledge claims are not merely the product of our cultural milieu? If we cannot demonstrate that knowledge is in fact connected to a real metaphysical reality, if we cannot prove it, how do we know whether or not any claims to knowledge are in fact real? What if they are merely the product of powerful people saying things because saying them benefits the powerful people? You might want to dismiss this outright, but this observation has validity. You can actually demonstrate historically how ideas are shaped for reasons of power, or simply to justify the predominant conception a people have of themselves. The proponents of critical theory recognize the infinite regression here, that even the critical theorist is merely asserting their own ideas as the will to power. The result is that true knowledge about anything becomes impossible. It is all just word games and power games. Something becomes true because I can impose it upon you. As these post modern ideas filtered into the general public, they put liberal ideas of emancipation on steroids. If there is no truth, then the only way to be free is to be completely released from all unchosen bonds that might then impose their truth upon us. To be truly free, you must live your own truth. But we get ahead of ourselves.

Gadamer, though, goes back to Kant to recognize within his writings a key concept for understanding the nature of how we grasp truth. Drawing on Kant’s work on ethics, he makes this observation:

“In fact, the logical basis of judgement—subsuming a particular under a universal, recognizing something as the example of a rule—cannot be proven.”

If it seems we are back at the fundamental problem arising out of Kant, we are. But the insight that Gadamer wants us to take away from Kant is that judgement itself is like a sense.

“It is not something that can be learned because no demonstration from concepts can guide the application of rules.”

From today’s perspective, the point that Gadamer wants to make from Kant is that you cannot develop a rational set of principles, a policy manual so to speak, that will always guide you to the correct application of principles in different situations. Think of the application of the Constitution. There is no methodology that can guarantee the correct application of Constitutional principles, including “originalism.” In a similar way, there is no way to guarantee the correct interpretation of scripture. This is the root problem with the doctrine of sola scriptura.

What Kant argues, says Gadamer, is that:

“Common sense (sensus communus) is exhibited primarily in making judgements about right, wrong, proper and improper.”

The point is that we all make judgments about right and wrong, proper and improper, or “is this a good ruling based on the Constitution or not,” or “is this a faithful reading of scripture or not,” within a community. We learn good judgment mimetically. It is this reality that opens the door to post-modernism. If all these judgments are really just things you picked up from the community is there any basis for knowledge at all? In order to push through to the other side, though, we must stare this reality in the face.

In this embedded social situation we are ready for the next layer of concepts, that of “fashion” and “taste.” Fashion is that complex of perceptions and judgments that are fully adapted to social life, and to the present social demeanor. It is what everyone does. It is that thing which is “in” at the moment. Fashion is memetic. It is one’s social context that is difficult to shake off. Taste, on the other hand, operates in the community but is not subservient to it. Taste makes the claim that everyone should agree with my judgement, but knows that not everyone will. Taste is a mode of knowing. It elevates one “above” the web of memetic fashion.

“It no longer recognizes and legitimates itself on the basis of birth and rank but simply through the shared nature of its judgements, or, rather, its capacity to rise above narrow interests and private predilections to the title of judgement.”

Taste is a mode of knowing. The mark of good taste is being able to stand apart from the web of memetic desires, from ourselves and our private preferences to recognize something which transcends private social inclinations in the name of a broader social application.

“One must have taste—one cannot learn it through demonstration, nor can it be replaced by mere imitation.”

It is not a private thing. It aspires to something higher, something that transcends. It also has a certainty about its judgments. The opposite of good taste is not bad taste, but no taste. Taste is a form of knowledge, like wisdom.

“It follows that taste knows something—though admittedly in a way that cannot be separated from the concrete moment in which the object occurs and cannot be reduced to rules and concepts.”

In the moment of the encounter, good taste comes into play. It cannot be predetermined beforehand. You cannot write a policy manual for good taste. Taste grasps the principles at play, and their proper application. Taste understands that the judgment made is “fitting” for the moment. This transcendent judgment cannot be demonstrated rationally, though.

“No one supposes that the questions of taste can be decided by argument and proof. Just as clear is that good taste will never really attain empirical universality, and thus appealing to the prevailing taste misses the real nature of taste. Inherent in the nature of taste is that it does not blindly submit to popular values and predetermined models, and simply imitate them.”

This gets us at the problem of mimesis. The difficulty with Kant, argues Gadamer, is that he denies that any significant knowledge can be attributed to taste. It has no theoretical content. This, argues Gadamer, is a mistake. By severing taste from real conceptual knowledge, all meaning simply becomes a web of fashion. This is the essence of critical theory. All knowing is fashion.

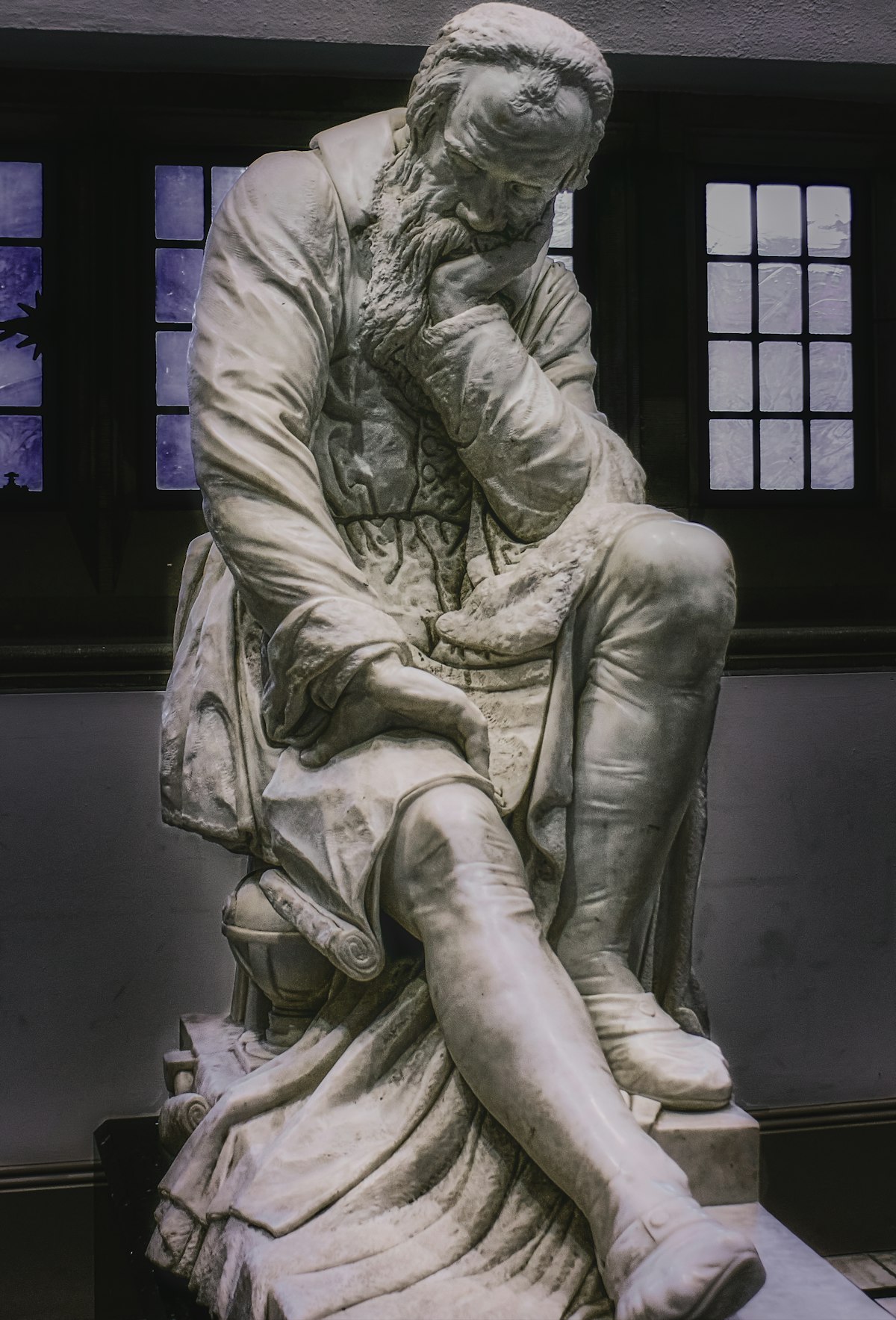

Using aesthetics and art to open this idea up to us, Gadamer argues that because of this lack of conceptuality, that beauty lies beyond all concepts, Kant leans into the idea of “genius” to formulate the core of his aesthetics. There is a certain irrationality to the genius that is evident in both the creator and the recipient, that one grasps the “content” of art intuitively using one’s personal genius. This thing that is grasped can never be expressed fully in any language. It has no conceptual content.

As we move from Enlightenment Rationalism into German Idealism, this idea of personal genius is picked up and developed further. All art becomes an expression of genius. But this genius is an expression of something larger: “spirit.” In Idealism, this notion of “spirit” usually refers to the spirit of a people, their shared ethos or culture. Out of this, the genius of the people is expressed in the genius of the artist. The concern here shifts from the apprehension of beauty in material reality to the self-encounter of man in the work of art. One is encountering “spirit.” One is no longer dealing with reality, but rather with my genius connecting with your genius through the medium of art. This attitude arises in Idealism in part because rational, technical, scientific thinking actually cuts us off from direct experience of the world. We only encounter the world now through concepts. This is something McGilchrist notes as well. Heidegger used the word “enframed” to talk about how the modern scientific and technical world cuts us off from our ability to directly experience reality. Having been cut off from reality by rationalism, we turned to subjectivity, the expression of one’s personal genius to grapple with the problem of how meaning is formed.

Freed from concepts, even concepts like allegory and symbol, the argument is made that genius creates unconsciously.

“The moment art freed itself from all dogmatic bonds and could be defined as the unconscious production of genius, allegory became aesthetically suspect.”

Once we emerge from the other side of German Idealism, this notion of personal genius becomes the highest standard of value, not just in aesthetics, but morally as well. Shorn from all external concepts, though, all truth becomes the expression of one’s inner self, one’s personal genius. Hence, the emphasis today on “creativity.” One must release and instantiate one’s own inner vision. There can be no external boundaries or limits to one’s personal genius. Thus if one believes one’s self to be a woman when born into the body of a man, the true reality comes from one’s own personal genius. This is what is real.

The rationalism of the Enlightenment resulted in the severing of knowledge from any metaphysical grounding by denying that we cannot access the metaphysical as a rational concept. This leads to an emphasis upon scientific and technical knowing—sticking to the question of how things work. This shift resulted in a radical change in how we understood knowledge. The meaning and truth of things were no longer found “out there” in the world, rather they were found within one’s own subjectivity. The questions of morality, purpose and meaning are transferred to one’s own personal genius. One’s own inner truth became seen as determinative of truth itself. All attempts to “impose” an external truth would come to be understood, via critical theory, as inherently oppressive. In practical terms, though, what it has meant is that the content of people’s inner genius is largely the product of mimesis, imitation. There is nothing outside of our own subjectivity that grounds, limits or challenges our personal sense of things. There is nothing which measures or evaluates our inner sense of understanding. Everything is fashion and thus everything is mimetic imitation. This is doubly so in a world where we drown in propaganda. At that moment when we seem most free, we are the most in bondage because no external standard imposes itself upon us to tell us otherwise.

This notion of inner genius has also placed a tremendous burden upon us. Now each of us must “find ourselves.” We must uncover this personal inner vision for ourselves in order to achieve true fulfillment and happiness. It is what Mircea Eliade in “The Myth of the Eternal Return” described as the “burden of history.” Once mankind placed itself at the center of all events, rejecting both archetypal or Christian notions of time, he must assume the burden of shaping all events towards the fulfilment of human potential. I must find my purpose. I must follow my dreams. We must build a better tomorrow.

The burden to constantly create one’s self on the horizon of time is tremendous. You cannot simply “be.” You must always be moving forward towards a goal, the expression of your personal genius, the realization of your dreams. But none of us truly knows ourselves. Much of who we are remains opaque to us. We don’t even know where thoughts come from and yet we are to expect that within each of us there is a personal creative genius waiting to be expressed such that we can then establish and chart our own futures? It is no wonder so many of us just adapt ourselves to fashion and call it a day. Much easier to blend one’s identity into some assemblage of brands than it is to actually make it up for one’s self. In this way, the sea of propaganda messages which include advertising, grips us, surrounds us, and becomes our metaphysical archetypes, our divine reality, the god that we worship.

Christians and Christian churches fall into this way of thinking when talk about “God’s plan for our lives” or “God’s vision for this church.” We think that in phrasing it this we are separating ourselves from the broader culture. But, in truth, who is at the center? It is about me, having a special plan from God. God is now the provider of my personal genius. Or, it is about our church having a special plan from God. It is about God making us feel special. We are asking God to provide the special genius that will make our life meaningful. We see ourselves at the center of activity. But biblically it doesn’t work that way:

Jesus gave them this answer: “Very truly I tell you, the Son can do nothing by himself; he can do only what he sees his Father doing, because whatever the Father does the Son also does.” John 5:19

Jesus sees himself, he who is destined to be the Savior of the world, not at the center of things. Jesus sees himself within the web of the activity of God the Father. Jesus looks out and sees God at work and joins in with what God is doing. Doing the work of God as believers is not so much God having a special plan for our lives as it is about us bending our lives to what God is already doing out there in the world. More often, it looks something like this:

Now an angel of the Lord said to Philip, “Go south to the road—the desert road—that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza.” Acts 8:26

You have a busy schedule. You day is just slammed. God’s plan for you? Cancel all your appointments and go for a walk. Nothing more or less exciting. Will you sacrifice the plan you have do what God wants in the moment? We live within the theatre of God’s grand plan. He is always at work. Will you pay attention to what he is doing and adjust your life and join God in what he is doing no matter how much it inconveniences you, regardless of whether or not it fits into your personal vision for your life? Will you drop what you are doing to go for a walk?

This world of personal genius is the one we are raised into from a very young age. As children we are given pots of paint into which we are told to dip our hands and just “be creative.”

We must teach the children to free themselves, not think too much and just let their inner creativity out. By doing finger painting and other exercises, we start teaching them at a young age to unleash their own genius. Don’t be afraid. Have fun. Be creative. This is what much of the idea of getting in touch with our inner child is all about. Be uninhibited. Just let your creativity flow. Get into the “flow state.” We are told to dance as if no one is watching us. All of it is training us to be post-modern critical theorists. Get in touch with your personal genius. If anyone demands that you conform your life to external standards, they are merely trying to impose their biases upon you. They are trying to destroy your inner being. They are “literally” trying to kill you. They are making a power play that must be deconstructed.

All of this bias towards releasing our personal creativity simultaneously trains us trust above all else only our own inner vision of ourselves, our own morality, our own truth, while it makes us vulnerable to mimetic desires. We are at once products of propaganda while at the same time we lack any external references or standards against which we can evaluate the truth claims emerging from within. It is no wonder that there is an epidemic of transgenderism. But it is also not surprising that there is an epidemic of divorces. This same dynamic trains and prepares us to leave our spouses because in our marriages we feel “trapped” and we need to break free to “find ourselves.” Finger painting: ideological training for our modern world.

But is this really the case, that all creativity is the outflow of one’s personal genius? If I were musically inclined and wanted to play the piano, but simply sat down and started to express my inner genius like I was finger painting, we all know what it would sound like: a toddler banging on the keys before you close the cover and gently telling them the piano is not a toy. My wife teaches piano. It is a difficult instrument to play well. There are rules that must be learned. You must practice. You must fit yourself within the rules. You must do the work. You need a teacher who can apprentice you. It is a language that must be learned, one that is both heard and written. You must get a feel for the instrument. You must learn and respect the constraints which the piano imposes upon you. But, if you work at it, if you submit yourself to the master pianist and learn, if you are willing to fit yourself into the constraints of the instrument and the rules of the musical language, there will come a time when you will be able to express yourself well. You might even compose music of your own.

This said, it must be recognized that Western musical theory and notation built around octaves, eight-note scales, and their variations, is itself a rationalization that develops alongside of other rationalizations of the time. It is not an accident that Mozart is making music at the same time when Kant is writing his philosophy. This process of rationalization, and with it the resulting abstractions, does seem to cut us off from an intuitive grasp of the source itself. We see this most clearly in thinkers like Kant who severed us off from metaphysics because he could not develop rational proofs for its existence, nor could he explain its contents rationally. They simply had to be accepted

as a priori categories. This bias towards rationalism makes it hard for us to access the real content that is available to us in metaphysics, archetypes, symbols, metaphors and allegories. Most of all, it severs us from the real content available to us in our relationship with the transcendent, with God himself. By limiting knowledge to the rational, we cut ourselves off from all living sources of non-rational knowing, pushing ourselves towards a radical subjectivity in which the only source of inspiration available to us is our own inner creative genius. But because we are cut off from these external sources, we are no longer restrained by the limits they impose upon us. It is in this context that memetics can run free. Without any external limits, there is no restraint to our desires, nothing that tell us that it is not good to merely imitate the desires of others. Take, for example, in contrast, the reality of working with wood. The material itself grounds you. It has certain characteristics like hardness, grain, and moisture. Some woods are good for some applications, some for others. The material will expand and contract. It can warp. It has internal tensions that must be respected and released. Some of this knowledge can be passed on rationally. You can use words and concepts and talk about wood as a material and how to craft it into objects for our use. But a lot of learning wood is about learning the “feel” of the wood. There is real content to this knowledge used every day to build houses, cabinets and furniture, and a host of other things. But much of the feel one has for wood cannot be put into words, and cannot be expressed in concepts.

Language itself is like this. There is a part that is rationalized. There are words, there is grammar. But the meaning of words is separate from the words themselves. The purpose of language is to allow two people to communicate. Each person has their own unique set of experiences and thus their own unique set of associations with the rational signs and symbols of language. Yet, somehow, communication happens. Obviously, language is not some mere production of personal genius, otherwise, it would be unintelligible to anyone but ourselves. Spengler, correctly, argues that language is in part a “spiritual” thing, the result of a connection between people. The tighter the bond between persons in the community, the better and easier it is able to communicate with others.

“This fixed stock of signs and motives, with its ostensibly fixed meaning, must be acquired by learning and practice if one wishes to belong to the community of waking-consciousness with which it is associated. The necessary concomitant of speech divorced from speaking is the notion of the school. This is fully developed in higher animals; and only in every self-contained religion, every art, every society, it presupposes the background of the believer, the artist, the “well-brought-up” human being. And from this point each community has its sharply defined frontier; to be a member one must know its language—i.e. its articles of faith, its ethics, its rules.”

Spengler argues that in the life of a culture, it begins rooted and grounded in the soil, in the indeterminate knowledge of materials like wood, earth, and animals. It is also birthed in a much greater sense and awareness of the forms, the archetypes, and the metaphysical structures of the world, of God himself (not that Spengler had much use for the Christian faith). As a culture becomes aware of itself and begins rationalizing itself, thinking about its own artifacts, and attempting to understand it conceptually, this also severs it somewhat from the source of the culture: the people, the soil, the archetypes and God. As culture is externalized, this begins the battle over the concepts. This has been a particularly acute problem in the west because our cultural ascendency has been fueled through the realization of the power of abstractions as instantiated in technology and science.

We can also see this at work within the Christian faith itself, this process of abstraction that began in the scholastics, both Roman and Protestant. The Christian faith is conceptualized, broken down and examined. The attempt is made to rationalize and solve every problem, every contradiction, every mystery. But in so doing, we slowly cut ourselves off from the source, from that which truly grounds the faith. The faith is not grounded in the scriptures. The doctrine of sola scriptura is actually a part of this rationalization process, an attempt to limit and circumscribe the content of divine revelation so as to facilitate a better rational understanding of the faith. While it succeeds in this, at the same time it cuts one off from there being any real “content” in a person’s own relationship with the Divine. Even though the document itself shows evidence of a deep connection with the “content” of both life and a people’s journey with God, recognizing that much of this “content” cannot be grasped rationally, but can only be accessed through story, metaphor, allegory and symbol, the attempt has been made to systematize and rationalize this same content, turning it into a series of abstractions. In so doing, it severs people from a direct living relationship with God. One’s relationship with God is mediated and circumscribed by the content of scripture as this is the “sole” way God reveals himself. This is then further mediated by the contents of the theological abstractions drawn from the scriptures. If there is direct contact with God, it can only be in the domain of feeling. It can have no content.

Our response has been to turn to subjective emotional experiences in worship. We want to be moved emotionally. Emotion is equated with meeting God. We force ecstatic experiences upon ourselves. We want our worship to be “authentic,” in that it is a vehicle for us to give expression to our inner subjective feelings. We want it to recharge our batteries. The truth is, cut off from real the real experience of God —or at least cut off from the ability to recognize that we are meeting God, living as we do in a world of technical abstractions— we cannot see that we are a society that has a deep soul sickness: acedia.

Acedia is not a sloth. It is an illness of the soul. It is the desire to leave behind spiritual matters. It is a distaste for the things of the Spirit. Readings, prayers, rituals, and the company of the pious become repulsive to us. If given full sway, it takes away one’s desire for the eternal. It is soul-death. It is the thought, “Why am I doing this? Why should I put in all this hard work for the spiritual journey? What of grace?” To fix this problem, rather than doing the work, we start looking elsewhere. We convince ourselves that a new church will solve our problems and make better use of our gifts. We start chasing after emotional experiences, thinking that these highs will give back to us what we once had. The person in the grip of acedia, gripped with soul-sickness, has no energy, they are chronically fatigued, worn out. They just want what they had back again.

This is in many ways us as a culture, but particularly us as a church. One of the great spirituals, the Desert Father Cassian, argues that what is needed is for us to quietly do the spiritual work. Maintain the discipline of reading the scriptures and of prayer. But also, take time to work with your hands, with soil, with real materials. Do the daily chores of life, keeping house, cooking, even the routine of exercise, but do so in a manner where you let your thoughts go. Let prayer arise. Begin the practice of meditative prayer like the Jesus Prayer. Let your mind be awake, alert and receiving. The less actual thinking that you do, the more that you can allow the “content” of your work to emerge. The feel of the soil. The feel of the wood. The feel of the vegetables you are chopping. The feel of the laundry you are folding. Let your mind rest. Observe, receive and listen. In the end, the way through, and this will be hard for some Protestants to hear, is to do the spiritual work. The goal is to nourish the soul allowing it re-awaken to the real presence of God all around oneself.

Why mention this here? Because I am of the belief that there is something unique about the Christian faith. The West as a culture does not have this thing. The West was born, it lived, it had its shining moment in the sun and is now fading into its later years. The West was just something that happened. The Christian faith was intertwined with the West. We can debate the nature of that mix. But while the West has a strong Christian component and would not be what it is without Christianity; the Christian faith does not need the West to exist for it to be Christian. This is important to remember. Not only that, but the Christian faith is not something that emerged naturally out of the soil of a people. It was founded intentionally by God through Jesus. This was the point of gathering the disciples. Jesus taught them faith. “You feed them,” he told his disciples when facing a hungry crowd of 5,000 men. And when they were flummoxed by this command, he showed them.

The implication of this is that we can do this again. We can be intentional and re-found the Christian faith in imitation of Christ and his apostles. But it also means re-grounding ourselves in the true “content” of the Christian faith. Our culture has abstracted and cut itself off from the source of authority. Our society has a deep problem. No one is in charge. Not really. The systems, the abstractions, the science, the technology, they dictate much of what we do. We saw this exposed during the response to SARS-CoV-2. Beginning with the Enlightenment, we have gradually cut ourselves off from all the sources that nourish a living and vibrant culture. We have cut ourselves off from all the deeper forms of knowing because they cannot be verbalized, measured, and tested. If we cannot use it to harness resources, whether natural or human, it is somehow deemed irrelevant or suspect. We cannot ground our morality and thus we lean into the will to power. Might makes right.

Because it has rejected the Christian faith, and cut itself off from the tangible presence of God and creation for the power of the technical and the scientific, our society has nothing with which to replenish itself. Intellectually, all concepts have been explored and then deconstructed. Critical theory is the direct descendant of the rationalization that occurred during the Enlightenment. It is similar for something like music. Once its rationalized forms were fully explored, all that was left was to deconstruct it. Similar for art and architecture. Once the living forms were abstracted, developed and refined, severed from a living cultural source, all that was left was their deconstruction and commodification. Thus we are a society with deep soul-sickness.

Today, we as Christians live apart from our own faith, in an abstraction of our own making. We are very much like the “teachers of the law” in Jesus’ day. We pour over the scriptures like blind guides leading the blind. But what is needed is not emotion, it is not even “experiences” in the way we think of them today, as items of consumption. We need to do the work of connecting with God, connecting with the creation again. Get our hands in the dirt. The discipline of prayer. Grounding ourselves in the real presence and experience of God. To our rational selves, this makes almost no sense. How can you “ground” yourselves in experiences that potentially have no rational content? How is it that we ground ourselves in the ineffable? It sounds very suspect. But this is exactly what Carl Schmitt is intimating when he talks about the “miracle of law.” When you read Ecclesiastes 3 and are given the multitude of “times” how do you know which time you are in? How do you make the right choices? I will tell you this, if you try to “follow the science” you will have no answers. Worse, you will be lying to yourself about the real reasons for your choices.

This is the “content” behind the idea of “taste.” We thought that we could gain a more sure foundation for knowledge through the use of reason and the scientific method. But by cutting ourselves off from the real content which is in the physical world, the kinds of things conveyed to us as we touch and handle, we lose contact with this wordless content. We also lose touch with that “something” that liberates us from fashion, allowing us to develop a sense of taste, a sense of judgment. It is at once connected with the life of the community around us, but at the same time stands apart, confident in the truth of its pronouncements. There is something similar at play in story, metaphor, allegory, symbol and archetype. Most of all it is found in a real “grounding” in the presence of God. It is only by meeting God, trembling before him in an unmediated experience that we can be freed from the grip of memetic desire. This is the essence of wisdom. But our culture, including many within the church community, having cut itself off from God, have no protection from mimesis and thus no protection from propaganda.

Just as not everyone in the community has good taste, so too not everyone is able to grasp the “content” of wisdom. This is partly spiritual, but mostly it is a very practical wisdom. But it can only be had by reconnecting ourselves to the non-rationalized content of the physical, symbolic, metaphysical, and spiritual realms. The formation of the Christian community by Jesus and his Apostles, supplemented by the spirituals, shows us the way. Just as it was in the beginning, so too today, the Christian community can be re-founded, and the Christian culture can be re-ignited. But we must be willing to do the work of preparing ourselves for grace. And while the anointing of the Spirit as retold in Acts was a singular event, the process of preparation is not:

“Do not leave Jerusalem, but wait for the gift my Father promised, which you have heard me speak about. For John baptized with water, but in a few days you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.”

Wait. As we noted above, Jesus looked around and saw the Father at work and joined the Father in the work he was doing. Ours is a time of waiting and preparation. Doing the work of prayer. Getting our hands dirty in the soil. The daily disciplined routine of mundane tasks. Ours is a culture that wants to run ahead, harness power, and get things done. But the real work is not seizing the reigns of power in the old dying regime. Our task is to begin the process of birthing a new society. To that end, it must be properly grounded in the living presence of God among his people. It is out of that “content,” that infinite living well who is the Living God, that a new Christian culture can be birthed.

Not all will have it to the same degree, some less, some more. The men that have it the most are the men for whom we look. These are our new elites. Men who have gone up the mountain and have seen God. Men of real authority.