Get Sertified

A guest post by Don Baton

Recently Don Baton, pseudonymous author of the great unwoke classical music newsletter The Podium , sent me an amusing (but also not so amusing) account from New York, and I felt it was worth him turning it into a short satirical piece for publication. That short piece, on the steady suffusion of identity politics into the everyday choices of life, and what it suggests about the direction of our society, is below. – N.S. Lyons

A few weeks ago, on a routine stroll around SoHo, I found New York’s most virtuous restaurant. It’s called Urban Vegan Kitchen and it’s located at 41 Carmine Street.

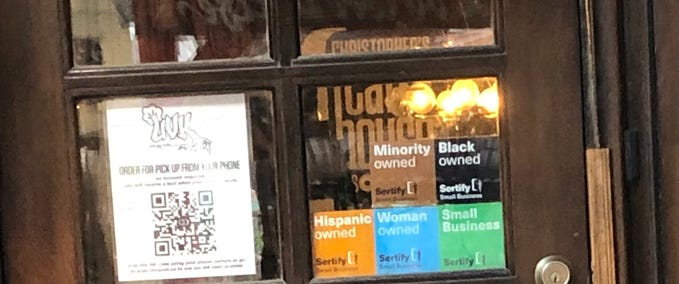

I cannot vouch for the food, atmosphere, or service at Urban Vegan Kitchen, because I didn’t go inside. But the five separate stickers on the door, reading “Small Business,” “Woman owned,” “Hispanic owned,” “Black owned, and “Minority owned,” were more than enough to convince me that had I entered, I would have achieved woke nirvana.

All of these stickers featured the insignia of a company called “Sertify” in the lower left. For which I give my thanks, as without Sertify I would never have found this Mecca of guilt alleviation. I can only hope that oppressed restaurateurs around New York will follow the lead of Urban Vegan Kitchen and hundreds of its peers and get “sertified.” Accumulating a full windowpane of sertifications may be hard for oppressed small business owners whose lives are difficult enough without needing to apply for yet another, uh, certification, but it’s worth the climb.

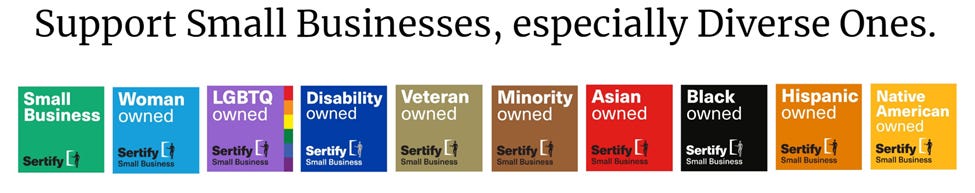

As Sertify’s website informs us, the process is simple. Underneath the company’s slogan—“Support Small Businesses, especially Diverse Ones”—we see the full panoply of available sertifications, each in different color stickers. Beyond Urban Vegan Kitchen’s enviable five stickers, Sertify offers “LGBTQ owned,” “Disability owned,” “Veteran owned,” “Asian owned,” and “Native American owned.” (In a subtle act of racial justice, Sertify made its Asian sticker red and its Native American sticker yellow.)

Businesses need only submit one proof of marginalized identity (along with $180) to receive their sticker. One allowable proof is a driver’s license photo, which we can only assume will be evaluated to ensure that the applicant merits their “Minority,” “Black,” “Hispanic,” “Asian,” “Native American,” or “Woman” designation. But those applicants who have a more—so to speak—Dolezal-esque relationship with their racial identity have options, too. For any Sertify sertification, “relevant social media content” is an allowable proof of identity.

Beyond the obvious financial advantage of enabling business owners to monetize the immutable characteristics they’ve worked so hard to cultivate, Sertify offers psychological benefits both to the business owner and the diner. For the business owner, I can only imagine the satisfaction of affixing both a “Black owned” and “Minority owned” sticker to one’s door. The only parallel I can think of is the thrill of a Scrabble player as he places a Z on a “triple letter score” square when his word has already earned a double word score.

For the diner, Sertify informs them exactly which moral nutrients they can expect out of their meal. They can know that their sandwich is not only gluten and cruelty-free, but assembled by a gender-nonconforming, Native American veteran. (Though, granted, there is some disagreement in Manhattan over whether veterans are a necessary part of a well-balanced moral diet.)

It is possible that as more New York businesses get in on the act, Urban Vegan Kitchen’s virtue will attract competition. In an identity-based version of the virtual reality game Pokémon Go, restaurants may try to “catch ‘em all.” Maybe someday, as such sertifications become the norm, New York’s city government will simply replace Sertify with mandated de-sertifying stickers such as “Not black owned” or “Not woman owned,” to warn the public about businesses unlikely to provide them with sufficient moral nutrition.

Draconian? Perhaps. But all to the good. In today’s world, we only “do better” by being willing to ask difficult questions. Questions like: “Sure, this place is Asian owned, Hispanic owned, and woman owned. But why aren’t the owners gay?”

I am clogging the airwaves of my good friend Lyon’s Upheaval with this attempt at satire for a serious reason. Over the last few years, elite America has acquiesced to the idea that patronizing businesses run by people with certain skin colors or genders is morally superior to patronizing those of others. Review aggregators like Yelp have set race-based financial targets for user spending at restaurants, and an increasing numbers of “directories” have sprung up, enabling consumers to earmark their spending by race, gender, or sexuality. Sertify is only one such directory, and a comparatively small one at that.

In general, the proponents of these efforts have little regard for the racism they demonstrate themselves, or for America’s dark history of white- or black-balling business owners based on race. Meanwhile, the reasonable people who make up the rest of our society are largely going along with this trend. Consumers passively stand by as the corporate giants they rely on daily, from credit card companies to their search engines, bombard them relentlessly with advertisements, email blasts, and “curated content” encouraging them to choose their purchases by skin color or gender identity. And business owners—whatever their personal qualms—are obligingly declaring their identities as (or their support of) oppressed classes in order to make a buck, or perhaps just to keep the mob off their backs.

This, it seems to me, is a consummate and concerning 21st century manifestation of Václav Havel’s famous greengrocer. In his undiminished 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” Havel describes a produce salesman living in a socialist society (much like Havel’s own communist Czechoslovakia), who posts a sign reading “Workers of the world, unite!” in his shop window. This, Havel tells us, is not an act of political solidarity so much as a gesture of deference to power—a forlorn prayer to be left alone. Havel writes:

Obviously the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit; he does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses. This, of course, does not mean that his action has no motive or significance at all, or that the slogan communicates nothing to anyone. The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains a subliminal but very definite message. Verbally, it might be expressed this way: ‘I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do. I behave in the manner expected of me. I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach. I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.’

Most of those who trumpet their support of minority-owned businesses in today’s America likely want little more than Havel’s greengrocer—to be left in peace. But one thing that ideological revolutionaries never do is leave normal people alone. Perhaps the best today’s greengrocers can hope for is that (to paraphrase Churchill) if they feed the crocodile enough, it will eat them last.

For more work by Don, check out The Podium, which I think quite expertly explains, preserves, and defends the history and beauty of classical music in the face of various barbarities assembled at the gates. Or listen to his recent podcast appearance with Glenn Loury and John McWhorter, on why he started the Substack.Subscribe