Dr. John Rae

Fur Trader, Explorer, & Canadian

The Canadian psyche is deeply informed by a primal awareness of the harsh land in which we live. As an early exploration of this, Today, The Red Ensign presents the story of Dr. John Rae, a Scottish-Canadian Explorer & business man who thrived in the vast Canadian arctic wilderness where most who went before or after him sickened and either gave up or died. Rae’s life and exploration also typifies the relationship of respect that existed between the Native peoples and early Canadians. Rae is most widely known for being the first to determine the fate of the Franklin Expedition, but as you will see, this was simply the best rewarded, both financially and in terms of public recognition, of his many great achievements in his lifelong battle with the elements at the frontier of civilization.

John Rae was born in 1813 in the Orkney Islands in the north of Scotland. He was the third of his brothers to join the Hudson’s Bay Company and leave this remote corner of the British Isles shortly after being licenced by the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh in 1833. After arrival in Canada, George Simpson, Commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company, assigned him the post of Medical Officer at the HBC post at Moose Factory. John Rae quickly adapted to his new life in the Canadian Arctic, becoming widely known as one of the best snowshoers and hunters of the Europeans in Canada. Over the next 10 years George Simpson would visit Moose Factory several times, a review of Simpson’s private correspondence shows that he believed Rae to be the most capable man in the company with respect to operating in the difficult conditions of the Canadian Arctic.

It is important to understand at this juncture the business and strategic position of the Hudson’s Bay Company in these years. At this time HBC had set up hundreds of interior trading posts throughout Prince Rupert’s Land, its business was dominated by the purchase of furs, and the sale of dry goods (textiles, rifles, knives, pots, kettles, tobacco, & liquor). Tally Sticks, and bone and silver tokens were used as a kind of currency between trading posts so that the native groups that did most of the trapping could sell furs at one post, and then buy supplies at another relatively seamlessly. Goods traveled in both directions via canoe & portage either to the coastal ports, or to the Great Lakes, and from there either to Montreal or to Europe for processing and sale. For this reason, HBC was aggressively interested in the mapping and exploration of water routes in the North West, in hopes of opening up new trading territory and eventually a cargo route to the Pacific.

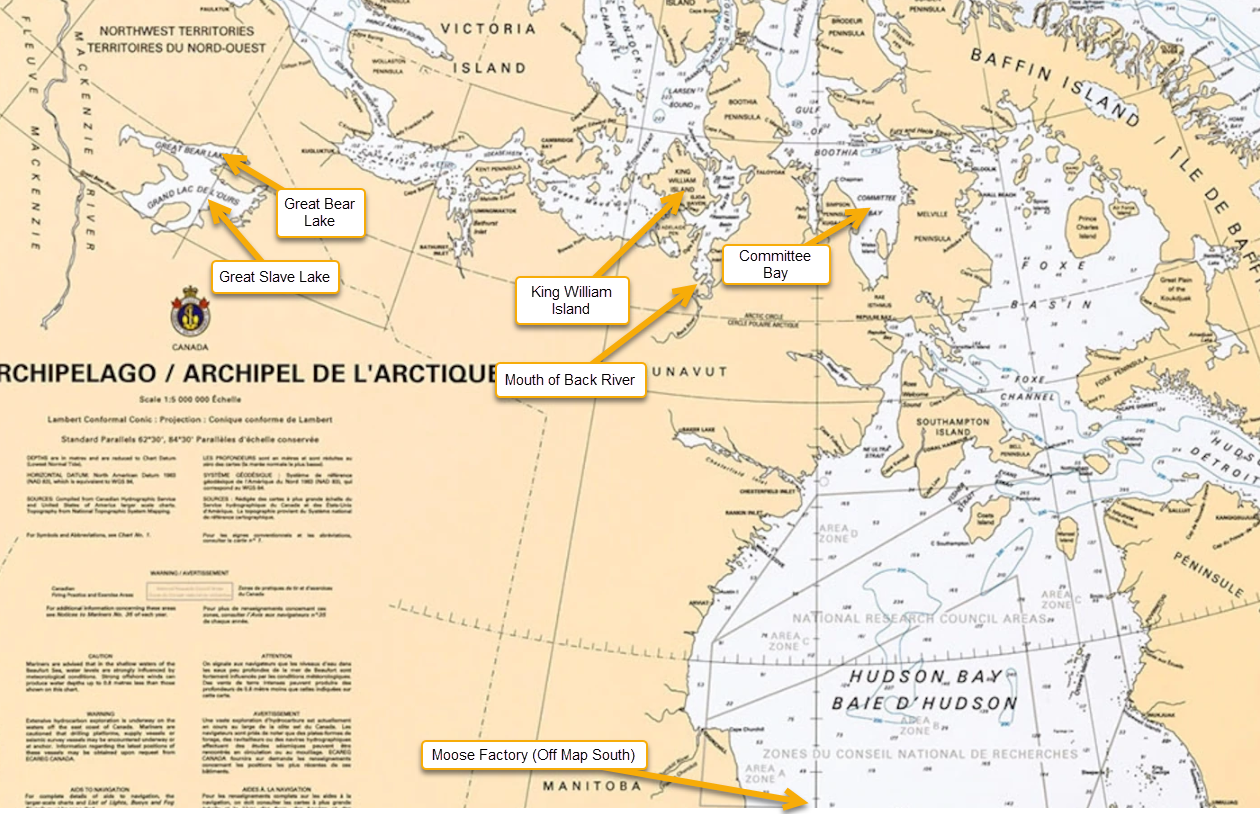

In 1844 Rae was selected to lead an overland expedition west from Hudson’s Bay to reach the farthest eastern point mapped from the west coast by Thomas Simpson. Before embarking, Rae was sent from Moose Factory to the Red River Colony to learn surveying from an instructor there. Rae’s first major expedition began on the Voyager route south-west from Moose Factory to the Red River Colony, 50 days of canoe and portage work in the chilled arctic autumn. Shortly after reaching the Red River Colony, his intended teacher died of an illness, leading Rae to make a further 1,200 mile journey by dog sled through the lake of the woods country, along the north shore of Lake Superior to Sault Ste. Marie. From there he was sent on another 400 miles to Toronto by more civilized transport, where he studied at the Toronto Magnetic & Meteorological Observatory. On August 5th of the following year, made the reverse journey, returning to the Moose River after a 64 day trek by Voyager routes through the vast muskeg of what is now northern Ontario & Manitoba.

On June 12 1846, Rae set out North with a team of 10 men in two 22-foot boats north to Repulse Bay. On information from local Inuit, Rae and his team dragged his boats 40 miles across the Melville to reach Committee Bay in the Gulf of Boothia. After discovering that the gulf of Boothia was a bay, and that he would have to cross land to reach Simpson’s Furthest-East, he and his team became the first Europeans to winter in the Canadian high-arctic without taking their provisions with them; living in igloos and hunting in the Inuit way. In April of that year he began again efforts to reach Simpson’s Furthest-East, eventually returning to the Moose River after the ice broke up on August 12th, failing to reach his objective, but reducing the unmapped territory in the North West passage to a gap of less than 100 miles.

In 1848 Rae was appointed second in command to Sir John Richardson on the search for the Franklin expedition, and was assigned to attempt the search overland. Over the next three years Rae would map thousands of miles of previously poorly explored Northern Canada, using small boats and either portaging them or hauling them over ice in the vast frozen-wetlands north of Great Slave Lake & Great Bear Lake. In 1851 he led another search party, mapping 700 miles of the southern coast of Victoria Island. In 1853-54 he led a third expedition in search of Franklin, mapping large areas of the Boothia Peninsula and proving King William’s Land to be an Island. During the course of this expedition he heard reports from local inuit, to be proved true much later, of the final fate of the Franklin expedition; That its men had perished near the mouth of Back River after losing their ship in the ice nearby. Rae obtained from the Inuit many items which belonged to the expedition (such as spoons and a small silver plate from the ship); which were enough to overcome the skepticism of the British elite, who attempted to deny him the prize for finding the expedition on the basis that British sailors would never have resorted to cannibalism as he reported.

After retiring from The Hudson’s Bay Company in 1856, Rae used the prize money he had obtained in finding the Franklin Expedition to finance the construction of a ship intended for arctic exploration. The ship was wrecked with all hands lost in 1857 in Lake Ontario, shortly after completion. He made a final surveying journey through hundreds of miles of the muskeg of what is now Manitoba in 1884, at the age of 71, for a proposed telegraph line from the United States to Russia via Alaska.

In looking at the life of John Rae we see the something of the best that the Canadian people can become; prying not only life, but a thriving joy out of the icy jaws of the great north. Embracing the best of the peoples who lived here before us, and laying the foundation for a great nation to come.

Rae’s own account of his journey’s - incomplete, and not published during his lifetime, can be found here: The Project Gutenberg eBook of Narrative of an Expedition to the Shores of the Arctic Sea in 1846 and 1847, by John Rae