Decline

A brief introduction to the history of consciousness

“No, listen,” I say. “Imagine this. You’re in an old aeroplane, the altimeter reads 5000 meters, you’ve lost a wing, you’re going down like a tumbler pigeon, and on the way, you’re going over your schedule: Tomorrow from noon to two ... then from two to six … dinner at six … Wouldn’t that be crazy? But that’s just what we’re doing!”

Yevgeny Zamyatin. We (1921).

So, listen. Imagine this. You’re living in South Africa. Everything around you seems to be tanking. Planned blackouts have been happening since 2007 and every year you spend more and more of your time stuck in traffic jams because traffic lights are out, and more time in darkness at night because your lights don’t work. Farmers can’t irrigate their crops properly. Automated animal farming is in crisis. Water doesn’t get pumped to some areas. The knock-on effect of constant power outages is almost endless. But, as if this were an infomercial for a catastrophe, that’s not all.

Prices are up. Government corruption is endemic. Infrastructure problems are everywhere. Crime is on the rise. Medical systems are in disarray. Education is institutionalised brain damage. More people are unemployed than employed. Maybe it’s time to look at moving to greener pastures. It must be going better elsewhere, right? Well, no. It seems not. Recession. Energy crises. Political confusion. If you’re a South African, the grass isn’t necessarily greener elsewhere. Maybe Spengler was right. The West is in decline. You pick the problems you’re willing to put up with, I suppose.

Anyway, let’s check tomorrow’s schedule, shall we?

Decline is a choice, people say. And I say, sure, maybe. Maybe it’s a choice. What people typically mean, though, is that decline is tangible. It’s objective. Just look at the decline of traditions, the dissolution of institutions, the dilution of identities, the decay of faith and reason and national pride, and so many other things. But then I notice that there is a particular consciousness that accompanies these observations. A particular mode of awareness. And I decide to pay attention to this. Why is decline noticed in the first place?

The examples I’ve offered above are selected out of a complex array of happenings. And everything else that is going on is not reducible to decline. What if we take the very noticing of decline as a sign of the times; as a sign that something is happening in us and not just around us? Why do we still see now what Julius Evola already named in 1961 as an age that appears “essentially” as an age of dissolution? And there were others before him and before them, and so on. Declinists have existed throughout the ages. Does decline mean more than just objective ruination?

Perhaps the best way to answer this question, although it may not be the expected way to answer it, is to look at the common assumption that there is such a thing as literal meaning, as opposed to metaphorical meaning—as if the literal and the metaphorical can be neatly delineated and are mutually exclusive. Generally the literal refers to taking words in their most basic sense. It implies the—it turns out mistaken—idea that there is such a thing as direct, neutral, unmediated meaning. The literal is apparently free from distortion. It is objective. A so-called literal translation of a text would therefore result from an attempt to be as exact as possible, not swayed by the excesses of imagination.

But the study of the development of language reveals that, in a certain sense, the literal as we typically understand it emerges from the metaphorical. One has only to consult St. Augustine’s Literal Meaning of Genesis to see this. What he thought of as literal was closer to what we might regard as literary. His interpretation of Genesis is wildly and wonderfully poetic. He sees in it far more than what any modern literalist would be capable of seeing. As this makes clear, the range of the literal has shrunk. Arguably, then, the consciousness that believes that unmediated meaning is possible is a shrunken and narrowed consciousness. It is a consciousness that has failed to be attentive to the preceding whole and so attends only to the framing of things that emerges once the whole is forgotten.

Decline means a general and widespread decay of the sense of total meaning. It means first that consciousness has deteriorated and only secondarily that there is palpable evidence of this in the world. This is a private as well as a societal occurrence. The literal, in the modern sense, involves an insistent refusal and exclusion of most of the meanings suggested by any word. The literal univocalises what is not univocal.

I think of ancient writers like Irenaeus and Pseudo-Dionysus who often refer to the receptivity of people with regard to how they make sense of things. “Those who see God receive life,” writes Irenaeus, “and this is why, though He is invisible, He made Himself visible and comprehensible to fit the capacity of those who believe.” But what if the capacity to perceive even that which has been reduced and dumbed down starts to decay? Is such a thing possible? Well, yes. This is what has happened. Decline means that the soil within which the seed of meaning can be planted and nurtured is no longer so receptive or fertile. For Irenaeus and other early Christians, Christ’s Incarnation was not a negation of his divinity but a manifestation of it. But consult the work of almost any liberal theologian and you’ll soon find that Christ has been turned into a mere man while his divinity is regarded as a mere subjective impression. Moderns call this progress. But the idea of progress is a comparative requiring a superlative to make sense. If the superlative is an enchanted world, the comparatively disenchanted world ought to bring tears to our eyes.

Owen Barfield is famous for having conducted a lifelong study of the development of human consciousness. He proposed that we need to dig deeper than any attempt at a history of ideas. A history of ideas would refer to “a dialectical or syllogistic process, the thoughts of one age arising discursively out of, challenging, and modifying the thoughts and discoveries of the previous one.” This is one way of looking at how thought has developed. It considers how ideas have evolved as if the substrate of human ideas has remained the same. But the substrate has changed dramatically, as Barfield is at great pains to demonstrate. It is not just objective things, things out there, that evolve. Consciousness also evolves. As Barfield says, “the full meanings of words are flashing, iridescent shapes like flames—ever-flickering vestiges of the slowly evolving consciousness beneath them.” There is no evidence that consciousness has remained static and ample evidence that it has changed.

Barfield does not mean that consciousness is necessarily improving. Here, evolution means change only. In any case, there is no such thing as a univocal improvement. Every development comes with costs even if it has a positive aspect, just as every form of medication comes with side effects. From one perspective, consciousness really does look to be in a state of decay. One has only to bother to read Jane Austen and then pick up a book by Danielle Steele to notice that something has gone wrong. The polyphonic mind of JS Bach has given way to the monotonous mind of Taylor Swift. The sculptural brilliance of Michaelangelo has been supplanted by the banality of Damien Hirst. Decline is a symptom. An evolution or degeneration of consciousness is the cause.

Barfield differentiates three epochs in the evolution of consciousness. The first he calls original participation, echoing the anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl’s idea of participation mystique. In this stage, consciousness is absolutely absorbed in its world; it feels its world to be always loaded, even overloaded, with meaning. At this level of consciousness, not much is differentiated. Differentiation has to be materially substantiated in actions, rituals, and occasional wars. For the person given over to original participation, the significance of everything is almost overwhelming.

Consider, for instance, Jesus’s declaration in the third chapter of the Gospel according to St. John that without being born “of water and Spirit” there’s no entering “the kingdom of God.” “That which is born of the flesh is flesh,” he continues, “and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. So don’t marvel that I said to you, ‘You must be born again.’ The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but cannot tell where it comes from and where it goes. So is everyone born of the Spirit.” We, two thousand years later, are likely to read spirit and flesh dualistically, although what Jesus means is much subtler. Spirit is one pattern of being and flesh is another. We are likely also to think of water as that stuff you drink and bathe in, although this meaning feels inapt here, doesn’t it?

There is truly a whirlwind of thoughts and images in this little passage so I’ll highlight only one aspect. Three English words are used here to make sense of and translate the same Greek word: pneuma (πνεύμα). All of these translations are apparently literal but the idea that they are therefore unmediated appears ridiculous. What we have in English is Spirit (the Spirit of God), spirit (approximating the spiritual), and wind (the physical thing that puts your hair out of shape on a blustery day). The modern mind has to separate out these concepts which would have been intertwined in the ancient mind. It wants to fix, to literalise if you will, what was felt to be equivocal for the mind enveloped in original participation. The modern mind, in other words, wants represented what was once only felt. Barfield calls this immediately felt sense of meaning figuration. It is less a kind of thinking or reflecting than it is a kind of pure recognition.

Barfield’s careful study of language, evident in marvellous books like A History in English Words (1926), Poetic Diction (1928), Saving Appearances (1958), and Speaker’s Meaning (1967), shows that the human experience was once almost entirely objective. For the earliest people, in other words, figuration seemed to come from the outside. When Thales of Miletus declared that everything was full of gods, he wasn’t being fanciful. The gods were not things to be believed in merely abstractly. They were very real and everything really was full of them. Arguably, they are very real but we have lost the awareness of, and the receptivity to, this layer of reality. In the Gospel of St. John, therefore, Spirit and the spiritual and the wind are not really separate or different objective things but are part of the same wholesome whole—entangled, intertwined, and interrelated. Moderns split and divide things up to control them but the ancients could let them be what they were: always a muddle of meaning in and around them.

Similarly, when Jesus said, “The Kingdom of Heaven is among you”—sometimes translated “within you” in Luke 17—he was referring to a total, universal, all-encompassing reality and not just some objective place that we can exit or enter like a room in some far distant castle in some far distant country. He did not mean belief as we meant it either. Belief was never abstract but, as its etymology implies, a lived thing. To believe was to love, care, and desire. To know had overtones of love-making, caressing, and desiring.

And so heaven was meant as a phenomenological and metaphysical pattern, a way of walking through the world. It was not just a conceptual decoration that we imagine in the same way as we imagine unicorns and a possible future in which computers have become sentient. Heaven was not some supposedly literal place we go to when we die but was, or rather is, an operative reality manifest in and almost volcanically bursting out from this very world we inhabit. Hell would also be a manifest pattern, although of a different kind. It would not necessarily be a literal place reserved only for the evil dead; hell would be a direct repression of the heavenly order even in this present world. It would mean the violent warping of the heavenly pattern.

The essence of original participation, therefore, is the sense that there is a deeper reality—unity, goodness, beauty, truth—behind all phenomena. Plato’s forms would be one example of an ancient philosopher’s attempt to account for this experience. He was not merely imagining the forms. He felt them. He belonged to them. Everything belonged to them. But trying to convince moderns of this is nearly impossible since meaning has been subjectivised.

Note: subjectivity is a kind of contraction of meaning. This doesn’t have to be a bad thing but there are extreme forms of such a contraction that aren’t beneficial to us. The modern consciousness has decayed so badly that heaven, for instance, has been divorced from existential resonances. But, thankfully, some remnants of its phenomenological and metaphysical dimensions can be found in common speech. “That chocolate was heavenly,” we might say. The modern hears: “I like chocolate very much.” The ancients would have heard and felt that the goodness of God is manifest in that creamy scrumptiousness. Truly, I say to you, unless you have been embraced by the gifts of ground cocoa seeds and of the loving labours of confectioners, you cannot enter the kingdom of Heaven.

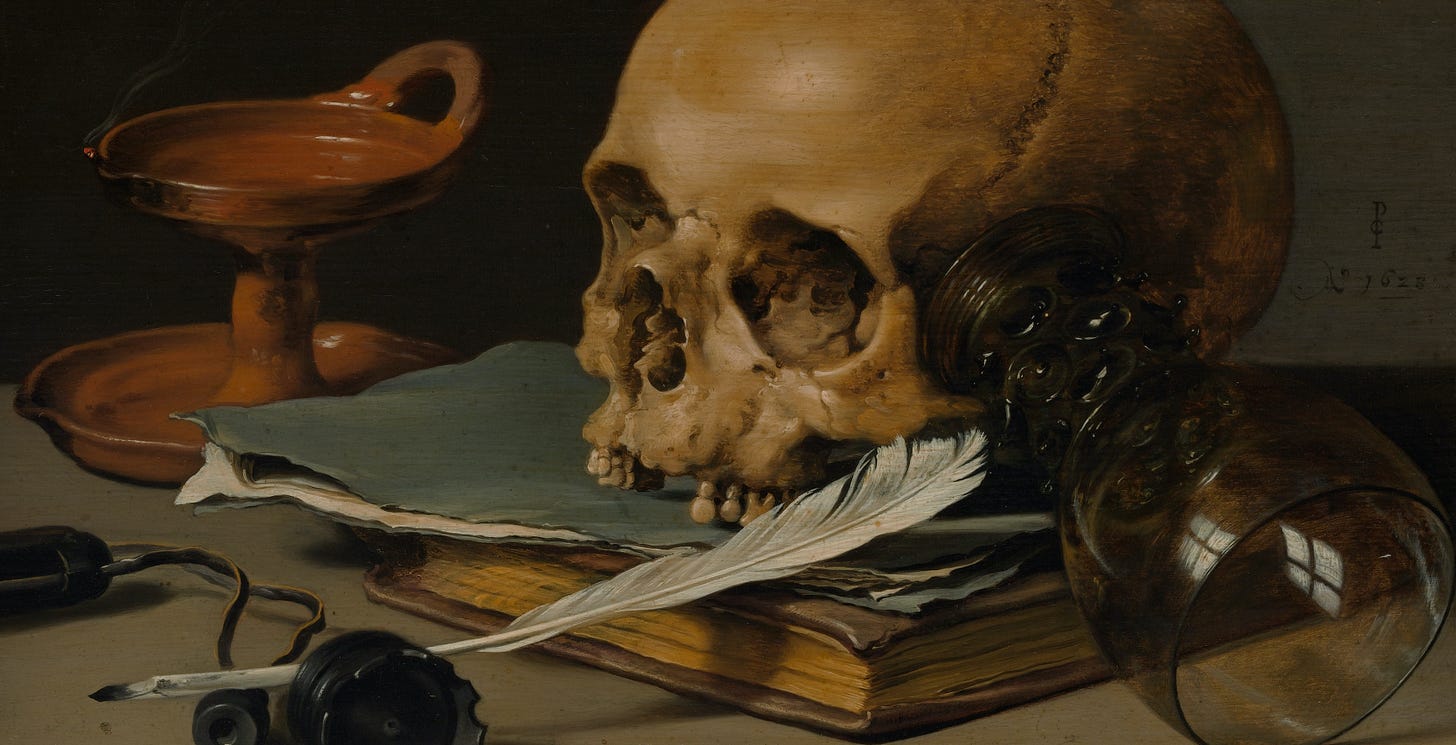

Something of this original consciousness is evident in the way medieval scientists sought an inner transformation through experiments with objective substances. Thus, Alchemy: an objective science conditioned by the consciousness of original participation. Look at children. Their minds have not yet been fully modernised. Biography recapitulates phylogeny. As we look back at our own lives, at memories of childhood in the autobiographical recapitulation of phylogeny, some of us are lucky enough to remember how thin to nonexistent the line between fairytales and the real world can be. The world we encountered back then was more drenched in meaning than we could articulate. That was one of the core facets of original participation. A poet like Homer, for instance, did not actually know that he was writing a poem. Poetry, for him, was his natural mode of perception.

But we all grow up, don’t we? Adolescence arrives with its knee-jerk rebellion against the given. Historically speaking, gradually, as Barfield finds, original participation began to make way for a kind of consciousness that looks upon the world of meaning always as if from the outside. Meaning became something we are forced to go window-shopping for without having the means to purchase what we find. Meanings started to separate and grow apart. The subjective and the objective became, at first subtly and then dramatically, divorced from each other. Let’s call this, in contrast with original participation, the onlooker consciousness.

Initially, such a consciousness reflected what was being experienced in original participation. Experience retained something of its richness in other words but gradually it took a back seat. Thoughts became increasingly abstracted from experience. As this onlooker consciousness gained primacy, theory began to usurp practice. The mind grew detached from the body. A sense of original participation grew feinter; the music of original participation grew quieter even to the point of being close to impossible to hear.

Some evidence of this shift in consciousness is found in the writings of the Hebrew prophets and in certain medieval writings. But it was only in the modern period that this onlooker consciousness began to really get a grip. One cannot read the work of nominalist thinkers like William of Ockham or Descartes or Francis Bacon without recognising an increasing distance from original participation. The sense that there was a reality behind things, to which all things referred, was being dulled. If St. Thomas Aquinas was fully aware that his abstractions were still connected to an original experience of participation, Protestant theologians started to think of God as an abstraction. He was becoming unreal—turning into a mere subjective tic. The real presence of Christ in the Catholic and Orthodox Eucharist became a mere metaphor in the minds of Protestants. God became a proposition, not a felt reality, as Nietzsche—that son of a Lutheran pastor—started to understand and convey in so much of his work. The modern drift towards nihilism was foreshadowed by the Reformation.

There was a clear benefit to this onlooker consciousness, though. The “I” emerged. If original participation offered only a vague and vaguely differentiated sense of self, onlooker consciousness was much clearer about this. The poet could suddenly see that he was writing poetry. The division of subject and object allowed for this. There was “I” and there was “not-I”. And so it has, on the whole, remained. This benefit came with a nasty side-effect, though, especially as the observer consciousness accumulated and believed its own theoretical assumptions. Theoretical thinking usurped participation. What was real became, quite suddenly, metaphorical and then later merely, boringly, constrictingly literal. The reality previously experienced as participation in formal causality became almost stupidly subjective. The subjectification of meaning, the transformation of meaning into a private experience, meant that the objective world could only be perceived as dead.

Ontology was replaced in the modern era with epistemology. And the concern with semantics ballooned. Modern individualism was one of the products of this shift in consciousness but so was modern ethics with its utilitarian drift. I recently read some secularist’s attempt to make sense of a certain religious ritual from the outside, trying to use his onlooker consciousness to understand original participation. The problem was not that the ritual didn’t make sense but that he could not even imagine feeling what those involved in the ceremony were feeling. The consciousness that transforms intimacy into spectacle cannot touch the meaning of things. Moderns think, “Ah, those poor people. How naïve they are to believe in the make-believe.” They do not notice that they are the truly naïve ones.

Barfield does not say this in his work but I think that electronic media, having a retribalising effect, have only helped to sediment the hypertheoretical onlooker’s mind in society. Such a constricted consciousness has become a surrogate for original participation. Original participation still happens in a widespread way, in other words, only now it happens within a near-total simulation. Is this what Baudrillard means when he writes of the simulacrum? The sense that there is a reality behind the simulation has been lost. We have only the theory and no reality to support it. Consciousness grows numb to deeper resonances and hermeneutical overtones. Meaning keeps shrinking. Literalising starts to take over. That is decline. We possess great sophistication while having lost a sense of holistic meaning; we have more information than ever but not the wisdom to be able to contextualise it and use it to our benefit.

Positively speaking, of course, the sense of decline may derive from a strong idea of a standard by which one can measure things. A person with a clear and coherent worldview is able to judge with much greater clarity what is wrong with the world. It goes wrong when it loses sight of what is right. This is not what I am considering here, though. As I suggested right up front, there are signs that a sense of decline can be a manifestation of the very contraction of consciousness that emerged in the modern era and which, in the postmodern era, has somewhat ossified. I’ll put it more bluntly: Decline may be manifest already in the very observation of decline in the world. If the plane is going down, we may notice this, in part, because the plane is an extension of us.

We are prone to act in the world in such a way that our assumptions about the world, even our most wrongheaded assumptions, are proved correct. Part of why I am writing this is to challenge this tendency. We were never freed from original participation after all but that part of us has been silenced often enough that we can quite easily convince ourselves that it is of no consequence. I can cite so many examples of how we convince ourselves of what we already believe but will, for the sake of brevity, offer only a parable.

I think of a dog kicked down repeatedly by cruel people who explain that they are punishing the animal because it resembles a wolf. That is their conviction. But they want it to be true. Eventually, aggravated and enraged, the dog bites back. The tame beast acts exactly like a wolf. “We knew it was a wolf all along,” those people will say. I often wonder if this is not how totalitarianism and fascism will return: out of a fear of totalitarianism and fascism. That’s how so much of life works. What we look for in the world we find. We will find even what isn’t there if we look hard enough. We will bracket out the good and see only decline. And then, by seeing only decline, we will contribute to its perpetuation.

Our task may therefore be, as Heraclitus suggested, to expect the unexpected; we should look for more than what we expect to find; we should be open to the good and not just the bad. I don’t mean at all to suggest that we need to adopt Pollyannaism, which is simply the opposite bias to that of the declinist. I do mean to suggest that we should learn to affirm the truth wherever and in whatever state we find it. “Live not by lies,” said Solzhenitsyn. That is what I mean.

Fully recognising the failings of a contracted and constricted consciousness, Barfield suggests the possibility of a third epoch of consciousness. He calls this final participation. There is a kind of reflective awareness at this stage, a bridge built between original participation and the onlooker consciousness. What is learned as final participation can sediment to transform the rest of our consciousness of the world. This was recognised by many of the Romantics who gave up trying to look for faeries in a disenchanted world and instead sought to nurture within themselves the imagination that would free them to be open to the possibility of re-enchantment. The subjective dimension can be used to restore a sense of wholeness.

If original participation, as Barfield says, “fires the heart from a source outside itself” to have “the images enliven the heart,” in final participation “it is for the heart to enliven the images.” We need, in other words, to cultivate the kind of receptivity or capacity within ourselves that would allow us to be filled not just with decline but also with the spirit of regeneration. This is not so much about transforming the make-believe into reality as it is about training our minds to be genuinely receptive to something that the ancients once knew first-hand. There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy.