Conspiratorial realism

A rather rough speculation on why conspiracy theories might turn out to be true

It is remarkable that very young children, without ever being taught, will realise that absolutely nothing in the world explains itself. This is what’s behind that infamous why phase. Kids will ask why until grownups, often confronted with the alarming limits of their knowledge, grow too exhausted to answer. As we get older, the intensity of this intuitive sense and questioning of the contingency of everything diminishes. And yet the feeling remains, albeit sometimes well hidden. We know that things rely on what they are not to exist as they do and to mean what they mean.

I want to work with this basic fact—that is, with our basic sense that things are always and in every way dependent—to explain something of how we have ended up with what some have called conspiratorial realism. What is meant by this is the fact that certain conspiracy theories have turned out to be true. Many examples of this exist all over the place. And we’ve seen memes about this. “Have you thanked a conspiracy theorist today,” says one. And another says, it is false that “conspiracy theorists think that everything is a coverup.” The truth, it suggests, is that they “question everything, do [their] research, and come to conclusions that scare [us].”

To offer a rough explanation of conspiratorial realism, it helps to keep in mind the age-old problem of habituation. I’ve already hinted at this above. We tend to get used to things or habituated to them; we start to take them for granted. In G. K. Chesterton’s 1901 book of essays called The Defendant, he points out that people “are continually tending to undervalue their environment, to undervalue their happiness, to undervalue themselves.” He writes that this is one possible meaning of the fall of man. “The great sin of mankind, the sin typified by the fall of Adam,” says Chesterton, “is the tendency, not towards pride, but towards this weird and horrible humility. This is the great fall, the fall by which the fish forgets the sea, the ox forgets the meadow, the clerk forgets the city, every man forgets his environment and, in the fullest and most literal sense, forgets himself.” It is likely, he offers, that we still live in Eden, only we cannot recognise it because our eyes have changed.

Marshall McLuhan, who was profoundly influenced by Chesterton’s thinking on this front, notes the same thing, namely the “phenomenon of the imperceptibility of the environment as such.” Many others have made the same point, like Martin Heidegger who endlessly mourns our forgetting of being and David Foster Wallace who talks about the invisibility of the water we are swimming in. We all have blind spots, these thinkers point out. And we are often blind to the very world we live in. Still, always beneath our failure to perceive the world clearly is that lingering sense that things do not explain themselves. The question of why is always lingering in the shadows of our own lives.

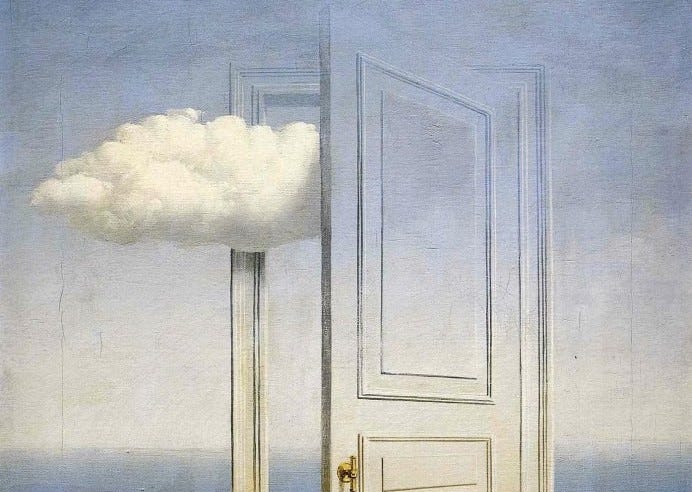

McLuhan suggests that the “overall pattern” of reality is likely to elude perception only insofar as there is no anti-environment or counter-environment. Because the environment is constantly imposing itself on us as a natural thereness, and so also as something that numbs us to our sense of things, we need a bit of friction to jolt us back into awareness. This friction may take on many forms and can be mild or extreme but the basic principle is the same: the counter-environment helps us to perceive the environment.

This may be what drives a great deal of human achievement. Perhaps it is precisely in an attempt to recover the world and perceive it more clearly that people have created machines and bureaucracies and philosophies and travel plans and a whole host of other things that in fact oppose the given world. Still, keep this in mind when considering how a conspiracy theory might arise in the midst of the chatter. Something happens and is reported by various people. Often these people have an agenda. They are paid to have an agenda. But here, at least two rather significant things are likely to occur that those who control mainstream media messages may not be ready for.

The first is that their explanation of a set of events will be felt to require its own explanation. Nothing accounts for itself, after all, not even our own explanations. We may even feel that the explanation does not explain the things it is trying to explain. In other words, the account may be thought not only to be incomplete but actually insufficient or even downright false. We naturally assume that there is more going on than what is surfacing. Add to this a second thing that is likely to happen, namely that an anti-environment or counter-environment will be sought. To perceive anything clearly, after all, requires what Byung-Chul Han calls negativity. Like children, we will start asking why again.

An anti-environment can be anything that generates sufficient friction to allow us to perceive something more clearly. An explanation can be an anti-environment but so can a protest or an advertisement or an accident. We have a range of possibilities open to us to generate an anti-environment when habituation and over-familiarity have taken over. Some anti-environments may be events, like news events. Some may be theories, like a good conspiracy theory. Notice: conspiracy theories are perceptual phenomena. This can get complicated but it is worth considering, just for a moment, how a conspiracy theory is a kind of folk phenomenology. I mean folk phenomenology to imply an account of experience by someone who is not a trained philosopher or phenomenologist. The aim is not rigour but atmosphere. If you consider a conspiracy theory poetically, you are much more likely to figure out its meaning.

Let’s take the famous flat earth conspiracy theory as an example. On a literal level, flat earth theory is wrong. We can mathematically prove this even without flying into space and looking down at this giant cloud-decorated ball of blues and greens we live on. However, at the level of what all of us experience, the earth really is flat (or, at least, flattish). My experience tells me that the sun is a luminescent disc that rises and falls and not a massive star that the earth revolves around. My experience tells me that the earth is standing still, not spinning like a top in a vast cosmic vacuum. Of course, flat earthers would want me to take their theory literally, just as Copernicans want me to take their heliocentrism literally. But thanks to my being aware of a little folk phenomenology, I can reconcile these two perspectives rather easily. I think Copernicans are better scientists, while the flat earthers are better phenomenologists. I can accept that they are both right, in a way.

Here’s another mad conspiracy theory to consider as folk phenomenology. 5G caused the coronavirus pandemic. To this I say, well, of course, it did. I mean, at the level of experience it did. I don’t mean that the virus spread through our wires and signals. That’s not possible. Rather, what I mean is that our entire experience of the pandemic was, long before the virus came to the places we live in, structured by the information we got through the internet. Our actions and policies and so much else were environmentally conditioned by electronic media. What a conspiracy theory like this shows, which phenomenologists would say is true, is that our experiences are far more undifferentiated than more rational theories tend to account for.

So here I am asking you to think of conspiracy theories in phenomenological terms. After all, it is at this level that conspiracies are likely to arise. What the conspiracy theorist is better at, on the whole, is allowing their natural contingency sense to have a real say. Unfortunately, the conspiracy theorist typically doesn’t notice that they are in phenomenological territory. They mistake their folk phenomenology for a scientific theory, and as a result, although not always, commit the classic fallacy of begging the question. They import their already-arrived-at conclusion into the premises and structure of their arguments. Any evidence that does not confirm what they already believe is soon discarded.

This happens at an interdividual or collective level and not a strictly individual one. The word conspiracy suggests this. Etymologically, it comes from the Latin conspirare, which means to agree or to plot. More literally, the term suggests breathing together, because spirare means to breathe and con means together. There is a spirit in all conspiring—a Zeitgeist, if you like. This means that what’s going on is not a private perception of things but an interdividual perception. There is a mimetic component to all conspiring. What is most central to the arrival on the scene of conspiracies is, therefore, probably not the accuracy of the theories themselves but what they mean, phenomenologically and relationally, for the people who are conspiring. The conspiracy theorist cannot keep his theory to himself. He must share it.

I mention this collective aspect in light of the fact that, since we are all connected via wires and signals, our own perceptions are bound up in the perceptions of people across the globe. At the level of folk phenomenology, we easily fuel each other’s thoughts. In seeking a counter-environment, we can support each other’s contingency sense and questioning and answer-seeking. Electronic media, by being the literal expression of the multiverse, allows us to encounter everything, everywhere, all at once. Terror is a fairly normal state in our hyperconnected society because everything affects everything else. Distrust metastasises rather quickly, too, but so, very importantly, does pattern recognition. “At the speed of light,” says McLuhan, “everything is illumination.” In being immersed in a digital world, I do not encounter facts so much as patterns. My world is not a world of objects as much as it is a network of symbols and meaning-events. Truth is not non-existent here but it is slightly more difficult to pin down.

This explains somewhat why so many conspiracy theories, especially in recent years, have proven true, or certainly as truer than the supposedly rational—let us say Copernican—explanations we have been given. If you can see the pattern quicker than anyone else, you are more likely to be right.

One example is instructive, although I should mention that this simply suggests that the conspiratorial hypothesis is more likely to be true than the original officially endorsed hypothesis. Remember the days, not too long ago, when the lab-leak theory surrounding the coronavirus was labelled a conspiracy theory while the wet market spill-over theory was taken as a fact? Yet, as time wore on, more and more started pointing to the lab-leak hypothesis as the most reasonable explanation. What some of us saw early on, long before it became officially sensible to admit it, was that the patterns surrounding the lab-leak hypothesis made a lot more sense.

I don’t want to unpack the details of this specific conspiracy and why it has proved to be more plausible than the original hypothesis. I know we still don’t have all the facts anyway and are unlikely to get them given the politics of this issue. My point, however, is to suggest that it emerged through a combination of noticing the insufficiency of mainstream media accounts and seeking a better counter-environment or explanation.

It is vital to notice that conspiracy theories are social phenomena. They are conditioned by certain social expectations. Generally, conspiracy theorists carry with them a stigma of being of a supposedly lower class and of a lower intelligence. There is, in this interdividual perception, something that people of a supposedly higher class and/or intelligence like to disdain. On this, I just want to point out two things.

First, there is a distinct possibility that more educated people, being more literate and so, therefore, more prone to accepting the fixed and linear perspective of the printed word rather than the flexible, multi-perspective of electronic media, are more likely to fail in pattern recognition. Jacques Ellul suggests that modern education primes people very nicely to accept propaganda at face value because it primes them to accept information in a decontextualised form. Ironically, the most educated are also the most likely to be duped. Intellectuals, who take in more information second-hand than others, feel obligated to have an opinion on all pressing contemporary concerns and assume, more than others, that they can judge all matters for themselves. Also, pattern recognition isn’t their jam and submitting themselves to people in a lower bracket in the social hierarchy doesn’t appeal to them.

Second, people who obsess with unworlded Copernican knowledge tend, as Ellul also points out, to place facts at a higher level than values. “Modern man worships ‘facts,’” says Ellul; “He accepts ‘facts’ as the ultimate reality. … He believes that facts in themselves provide evidence and proof, and he willingly subordinates values to them.” In contrast to this, being reflective of a somewhat pre-modern sensibility, albeit with modern literalising thrown in, what the typical conspiracy theorist or accidental conspiracy realist can be praised for, even if he happens to be wrong, is that he challenges this very thing by means of his pattern-recognising. The conspiracy theorist refuses to place what is valuable to him below what is factual. This may seem like sheer irrationality to any literate rationalist until he realises that the elevation of facts is reflective of a different set of values that are not necessarily in anyone’s best interests. What is essential in this regard is to ask the question of what values are in play and what is really worth valuing.

So there you have it. A conspiracy theorist may turn out to be right on the basis of a sense that greater negativity is required than is provided for by a given explanation, as well as because he is good at pattern recognition. He may also, in the end, turn out to be wrong, especially if his acceptance of certain facts is rooted more in tribal allegiance than in genuine truth-seeking. That said, recent times have shown us that simply dismissing a conspiracy theory because the wrong sort of people espouse it is reflective not of wisdom but of a rather myopic snobbery. What I’ve also tried to suggest is that conspiracy theories in general call into question the idea that there is only one way to truth, via modern scientific materialism. A much more nuanced view of truth is needed. We need to allow ourselves to look at conspiracy theories again, not through the ridiculously narrow lens of mere fact-checking, but through a broader lens that allows us to throw into question our own assumptions about what it means to make sense of the world.