Immigration Vibe-Shift?

On the recent hardening of language around immigration

There’s been a noticeable hardening in rhetoric regarding mass immigration in Britain recently, so much so that I thought some brief commentary was warranted. Naturally, we’re in an election cycle, traditionally the time the establishment parties lie the most and pretend to care about our wishes. Yet, much as I distrust him and despite the fact I’m struggling to become in any way enthused by the election, Nigel Farage was correct recently when he spoke of ‘‘something is happening out there!’’.

About 20 years ago, I worked in the petrochemical industry on the continent and spent a lot of my time in Holland. Returning to England for a break I met an old friend for a day’s drinking in Newcastle. The New Labour money had begun streaming into the North East, and Newcastle’s quayside was undergoing something of a facelift. Tyneside’s Brutalist architecture was transforming into the soft, formless curves of Neoliberalism’s preferred glass and steel.

The Millennium Bridge opened in 2000.

The Sage Opera House opened in 2004.

Neoliberalism was at war with the remnants of industry, concrete, and the old left of unions and working-class men who could build ships and mine coal. This new world, this ‘‘vibe-shift.’’ was feminine and, despite being constructed entirely out of glass and slender cables, was not transparent in the least.

My old mate was hardly a creature of politics, though he was prone to latching onto fads. He was excited about the ‘‘new life’’ being quango’d into Newcastle’s post-industrial malaise, and there were people popping up from faraway places, which made him curious. There was a novelty in meeting somebody from Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Algeria, etc.; it leaned into the Generation X wanderlust that we had both partaken in; indeed, in the early to mid-2000s, we were both engaged in it. The first trickles of the Blairite immigration surge, particularly into the North East, which was still about 98% white, allowed for the immigrants themselves to be thought of as mere individuals with their own stories to tell and cultural traits to divulge.

I was far more skeptical and already being called a Nazi and far right in the wider social circles, albeit in a lighthearted fashion. I tended to view the changes happening in terms of demographics and the multitudinous horror stories I’d heard about in Rotterdam and Brussels; my old mate processed it through personal interactions. They weren’t all bad, after all, and some of them liked Oasis. Some immigrants had genuinely interesting stories to tell, while others were interesting merely by being ‘‘exotic’’ and different.

The world was on the move, and you either got hip with it or remained behind, stuck in the past. Progressive theology came with globalism, like those small feeding fish that cling to sharks. Within this paradigm, our own people began to be seen as inherently ignorant and lewd, as low-status. The media facilitated with unbounded relish and enthusiasm, casting the native British as dole-sponging scum not worthy of the dynamic go-getters arriving in ever greater numbers. A beautiful girl from school married an African immigrant and had a half-caste child with him. I was dumbfounded, but my schoolmates' general reaction on Facebook was that she had scaled up as if she’d managed to nab herself some sort of Congolese prince.

There was never a sense of a great debate taking place, with the winning side emerging victorious and then proceeding to implement its program because no discussion of any kind had happened.

There was no formal announcement that this is how things will be now. In the same way, neoliberal architects' glimmering glass and cable signaled transparency, not an insidious non-governmental HR bureaucracy that would oppress and harass the people in ways the monolithic brutalist soviet rip-offs could never comprehend. The slug-like construction of the ‘‘Sage’’ on the Tyne could have been built in Manchester, London, Hull, Glasgow, Chicago, or Shanghai for all the relevance it had to the people once called ‘‘Geordies’’. But this, of course, was to see the spider’s fangs flashing within its hole; the whole purpose, the entire ‘‘vibe’’ was to elicit within the subjugated people a sense of uprootedness, dislocation, and estrangement from kin and land, home and hearth.

This ‘‘End of History’’ formula promised a world in which individuality could flourish, all tastes and consumer choices would be catered to, all material needs met, and your social connections would be built upon such tastes rather than any innate characteristics.

Twenty years after my friend waxed poetic over authentic Thai food and the Afghani he’d met who had never seen a television, he sent me this.

To be fair to an old friend, he’d had any idealism scorched out of him long ago, though I considered this recent text symptomatic of what Farage referred to as ‘‘something happening out there’’.

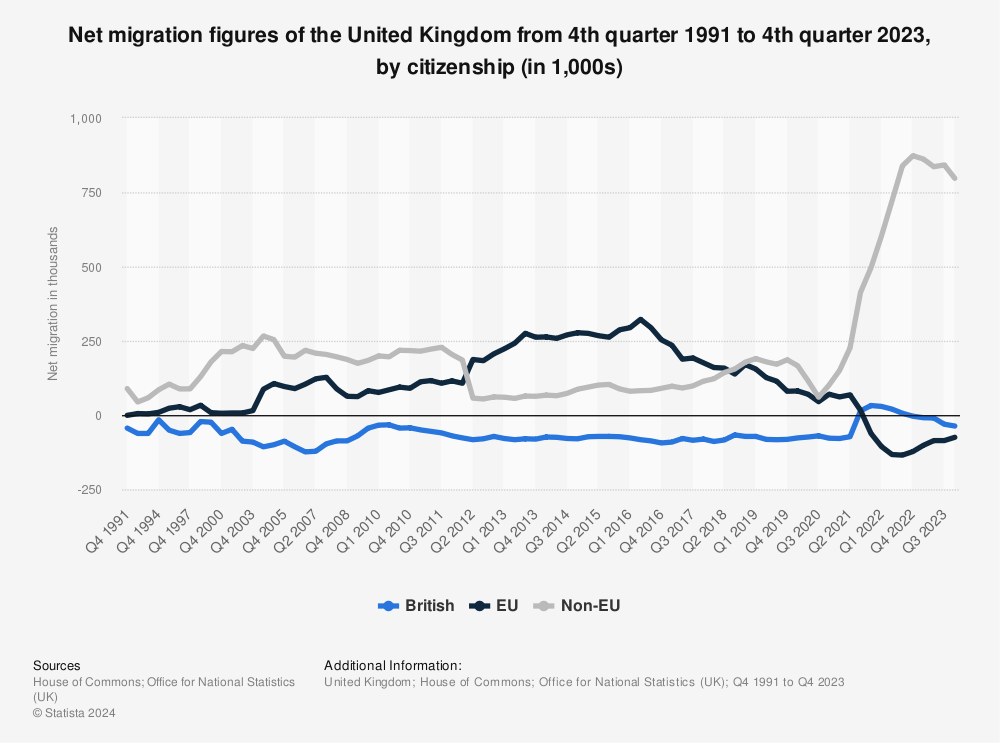

The mood change, and I believe there is one, is both tragic and refreshing. It is tragic because of how late it is; it is refreshing because it seemed as if we would merely dwindle into the bottomless ocean of Third World immigration after the centers of power checked populism. Despite the endless litany of outrages perpetrated within Britain by foreign imports, in the end, questions around infrastructure and the basic functioning of society appear to be hamstringing the project. We have been flooded to such a phenomenal degree, particularly since the Covid farce, that it is felt in the most rudimentary aspects of life.

Firstly, the aesthetics of the neoliberal world of twenty years ago have drastically altered. The glass, cable, and steel monuments to managerialism are still there, but they preside over hollowed-out and ruined high streets devoid of commercial activity beyond Turkish barbers and vape shops. In many parts of the country, you are lucky to be able to see a doctor or a dentist, and the cold technocratic logic mixed with the thorough alienness of the NHS strikes fear and terror into native hearts.

The sheer number of foreign people from everywhere has entirely negated any exoticism or interest in them as Radiohead-listening individuals. It is human nature to hold that which is rare to a higher standard of value than that which is common and mundane, and foreign peoples have long since lost any allure because of their ‘‘Otherness’’. Instead, the change in mood is reflective of our own people beginning to see themselves as a rarity within a miasma of limitless human biomass, which, despite appeals to cultural enrichment, by and large, is just thinking with its stomach as they arrive in rich pasture lands not their own.

Many years ago, I described the experience of watching the Olympics and having my eyes glaze over because I felt no investment in the morass of global humanity on display. I was touched when Laura Trott emerged, and I instantly recognized her as one of my own folk. I was reminded that we, too, were once a people. Within such a context of familiarity and kinship, individuals become more fully fleshed out and reveal to us a soothing melody against a wall of background noise.

Since the beginning of the multicultural era in earnest, we were bombarded with the word ‘‘tolerance’’. Yet, it’s a curiously negative framing of the project; we tolerate an ingrown toenail or toothache, and if we have the choice, we make it disappear. For me, a trickle of immigrants 20 years ago was a mild irritation and, for others, an interesting sensation. The pain threshold was supposed to be delayed indefinitely, or if we return to the question of malice, the amount of pain inflicted was irrelevant to those in power.

England was perfectly fine before we had Deliveroo and McDonald’s, yet now we’re supposed to believe that having Deliveroo and McDonald's is so crucial to the fabric of life that we must import their workforce. You will notice too that, contrary to the Globetrotting, wandering ethos of the early 2000s, any romantic ideals have evaporated like early morning mist and left us with nothing more than slave labour for corporate cartels. For this, we give up our freedom of speech, our feeling of belonging and home, safety, and numerical superiority in the land of our forefathers. The young will never own homes or, increasingly, never even be able to rent because the biomass is squeezed into every inhabitable dwelling in the country.

I used to regard arguments that focused on infrastructure and housing as weak sauce, purposefully picking the least incendiary ground to fight upon and avoiding the ethnic and racial elements. Yet, be that as it may, it is impossible not to notice the scale of degradation and decay and a future that looks to be infinitely more bleak than the past. In the minds of the masses, this decay and pessimism are associated with the foreign men stepping off boats wearing the cheap tracksuit and leather jacket combo.

People used to talk about moving to Australia or Canada, but now they talk about ‘‘Getting out’’ as if escaping a car that veered over a bridge into a river.

The sheer vindictive madness of Tory immigration policy means that having crushed and betrayed all nationalistic sentiment and socially ostracised critics of multiculturalism, the numbers brought in were so extraordinary that it threatens the basic functioning of Britain as a first-world country. Unlike terrorist attacks, causal knife crimes, or mass rapes, everybody is affected by clogged roads, extortionate rents, toothache, waiting lists, and the oddness of seeing African immigrants in every last corner of the country.

What Farage meant by ‘‘something is happening out there’’ is not ideological in nature; it is the reaction of a drowning man lashing against the hand holding him under the water. We’ve imported the Third World in terms of people, but our people are wincing and mortified by the fact that we’re now rapidly becoming Third World regarding material needs. For a system that is founded entirely on servicing consumerism, that is a problem because there are no more rabbits to pull out of the hat. Indeed, almost everything associated with the system has become low-status and grotty, not least the psychological trickery and linguistic control mechanisms of the bureaucracy, which, unlike in 2004, seems woefully dishonest, inadequate, incompetent, and anti-white.

The vibe shift is how I imagine the late-stage Soviet Union; nobody knows how long the system can perpetuate itself, but it won’t be forever. Vast swathes of the population both dread and yearn for whatever comes next.